Civil War Letters Come Home to Vermont

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – John McHenry, Class of 1963, estimates that he moved about 25 times during his 30-year career in the U.S. Navy, and every time McHenry moved he brought something precious with him: a wooden box with a hinged cover that his grandmother had given him.

Now the contents of that box – some 80 letters written in the 1860s by three Vermont brothers who served in the Civil War – won’t be moving anywhere again.

McHenry, 72, has donated the letters to the Davis Family Library at Middlebury College, where they are being digitized and preserved for future generations of students to analyze and enjoy.

The letters were written by McHenry’s great grandfather Benjamin Luke Quilty and two of his great-great uncles, John A. Quilty and George A. Quilty, to his great-great aunt Eliza Quilty of Brandon, Vt. The documents are rich in detail about redoubts and rifle pits, food and disease, and about the fighting and marching and waiting that soldiers, Union and Confederate alike, experienced during the War Between the States.

“I gave the letters to the College,” McHenry said, “because I am a Middlebury graduate, the letters have Vermont roots, and my grandmother Genevieve Quilty McHenry was from the Rutland (Vt.) area.”

During his years in the Navy and later as an analyst for Northrup-Grumman, McHenry occasionally took the letters out, read them and imagined the hardships his relatives endured, but he never thought about what to do with them until he attended his 50th class reunion last June.

“Someone else in our class [Susan Buckley ‘63] had donated Civil War letters to the College, and I thought, ‘What a great idea!’ In speaking with Rebekah Irwin [director of special collections and archives] I determined that Middlebury had a definite interest in Vermont’s contributions to the Civil War effort, and I felt that the College had the knowledge and the facilities to keep them from deteriorating beyond use.”

Irwin, who joined the Middlebury staff from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, has begun transcribing the letters.

“Some of the letters are so direct, so personal, written by three brothers to their sister when they were all in their 20s, that Middlebury students cannot help but feel how real this history is, especially when the writers are talking about the mundane details of their lives, and not just about the war,” Irwin explained.

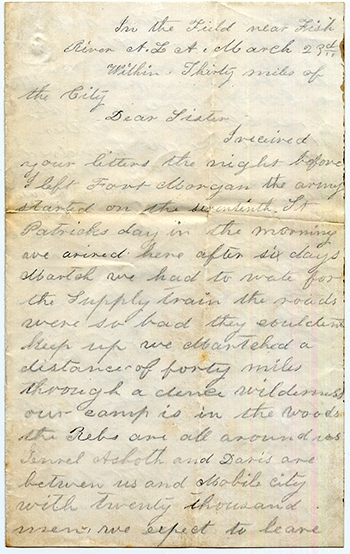

In one letter Irwin just transcribed, Benjamin Luke Quilty – the donor’s great grandfather – has just made camp outside Mobile, Ala., in March 1864. He writes:

We arrived here after six days march. We had to wait for the supply train. The roads were so bad they couldn’t keep up. We marched a distance of forty miles through a dense wilderness. Our camp is in the woods. The rebs are all around us. General Asboth and Davies are between us and Mobile City with twenty thousand men. We expect to leave here some time next week. General Thomas is marching down the Alabama river with a large force, [and] when the force all gets together it will be one hundred thousand strong. The rebs are said to be thirty thousand strong at the city strongly trenched. Our men are all in good health and eager for the fight. [Punctuation and capitalization added; spelling corrected.]

The “fight” Benjamin Quilty was “eager for” apparently didn’t come until August when Northern forces took control of Mobile Bay and seized the three Confederate strongholds that protected it. That triumph, together with the more-significant capture of Atlanta in September, signaled that a Union victory was close at hand and helped secure Lincoln’s re-election in 1864.

George A. Quilty was just 16 or 17 years old when he joined the Seventh Vermont Regiment as an Army drummer in 1862. He was discharged later that year due to an unspecified disability, but rejoined in 1864 and was dispatched to Conscript Camp in Fair Haven, Conn. That’s where he wrote this letter on August 28, 1864:

Sister Eliza, Here I am and happy as a lark with not a thing to mar my happiness. I arrived here safe and sound after a dusty ride of two hundred miles and was placed in the third story of a dusty lousy old building there being no less than 500 on the floor however I enjoyed myself tip top. Our grub is not the best nor the poorest, it just goes down and that’s all. … There are about 600 Vermonters here and we all bunk all together. Last night was my last night though. I was detailed today [to] one of the best in the U.S. They live high and have as good quarters as the officers. I will stay here my time out. Tell this to ma and she will be all right. There is an old sergeant punching me up and I will have to be in haste. Your brother. George [Punctuation added; spelling corrected.]

Primary source documents such as the letters written by the Quilty brothers can spark a Middlebury student’s fascination with research, the archivist Irwin said.

“Students often express a broad interest in a topic. For example, they might say they’re interested in the Civil War as it was experienced in Vermont, or in the early experience of women on the Middlebury campus, and then a newspaper article or a letter from the time period inspires them to dig more deeply into a specific event or historical character.”

Added Irwin, “The McHenry Family Civil War Letters can help students see that the typical Northern soldier was not a strict abolitionist. These letters may surprise some students about how Vermonters felt about slavery, but that’s what primary source documents do so well. They introduce contradictory points of view and the biases of people who lived through history, and then they rely on us to reconcile them.

Page 1 of Benjamin Luke Quilty’s letter to sister Eliza. To read both letters quoted in this story, please click here.

Californian John McHenry also donated Quilty family documents relating to enlistments, pensions, and land deeds, and a small number of letters from home describing conditions in Vermont during the 1860s. (It appears that Eliza kept the letters her brothers wrote to her, while most of the letters she wrote to them were not saved.)

But it is the act of writing letters – considered by some to be a vanishing art – that has archivists concerned about the fleeting nature of correspondence for the Millennial Generation.

“One of my biggest concerns is how do we collect the materials from students that will tell their history 50 or 100 years from now?” Irwin asked. Should archivists be preserving Twitter feeds and Facebook pages and email strings? Irwin doesn’t have the answer, but said, “The archivist’s role is to make us aware of our own mortality. Archivists remind us that we have a responsibility to tell our own stories in a lasting way.”

Students begin to understand how transient social media is when they come to Special Collections. “It’s an eye opener for them,” she said. “They get a real sense of how ephemeral their communications are when they get their hands on a scrapbook made in 1919 or on Civil War letters like these from the 1860s.”

Special Collections at the Davis Family Library is in the process of scanning the McHenry Family letters and will, in time, post them for the public. Inquiries about the McHenry letters or the Orlando French Collection of Civil War letters should be directed to specialcollections@middlebury.edu.

Reported by Robert Keren