Research Suggests Possible Black Hole Merger

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – Middlebury College astrophysicist Eilat Glikman is a member of the research team that made news this week with a startling discovery about the existence of two black holes circling each other in a distant galaxy known as PG 1302-102.

Glikman, the P. Frank Winkler fellow in physics at Middlebury and an assistant professor in the Department of Physics, studies quasars – galaxies with active black holes at their center – and their role in the formation and evolution of the universe. Her expertise at analyzing data sets on quasar variability helped produce the recent findings published on January 7, 2015, in the journal Nature.

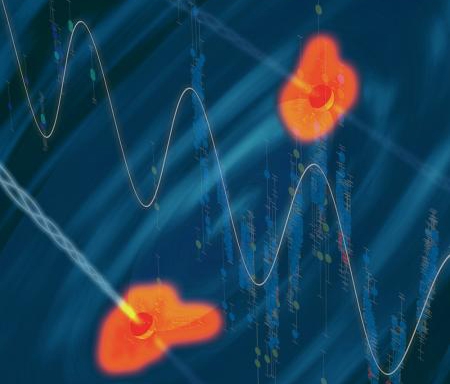

The black holes in PG 1302-102, which are less than a light year apart, demonstrate “a strong, smooth periodic signal of optical variability” every 5.5 years, which suggests that the pair could be in the final stages of a merger.

Glikman’s expertise with spectral analysis of quasar emission lines and her analysis of the near-infrared spectrum of light emanating from the quasar helped confirm the binary nature of the system.

In response to Nature’s release of the research paper titled “A possible close supermassive black hole binary in a quasar with optical periodicity,” the New York Times published a news story called “Black Holes Inch Ahead to Violent Cosmic Union.” On the same day the California Institute of Technology, where the lead authors of the paper are based and where Glikman was a postdoctoral scholar, released a news story titled “Unusual Light Signal Yields Clues About Elusive Black Hole Merger.”

Black holes, in themselves, are impossible to see, but their gravity can pull in surrounding gas and swirling bands of spinning particles at tremendous speeds, the Caltech article explains. These “accretion discs” of spinning particles release vast amounts of energy in the form of heat and light that Prof. Glikman is adept at measuring.

The next time the black holes are expected to pass by each other is in February 2020, and Glikman says, “Another periodic cycle would be a neat confirmation of our findings, but the data we have [from 20 years of observations of PG 1302-102] are pretty robust by themselves.”

“This binary is the first strong candidate for future gravitational wave indicators to point at with the potential of detecting gravitational wave signals. That would be a total game-changer,” the astrophysicist explains, “given that a detection of gravitational waves would be the strongest confirmation to date of Einstein’s theory of general relativity.”

The remote galaxy in question, PG 1302-102, is 3.7 billion light years away, as compared with the brightest star in our sky, Sirius, which is only 8.6 light years away from the Earth.