Literature, Learning, Loving Vermont

Literature, Learning, Loving Vermont

You know, you’re in a relationship with the people you’re teaching, and it’s a two-way street. They’re teaching me as much as I’m teaching them.

By Devin McGrath-Conwell ’18.5

Photos by Oliver Parini and Zovco Photographic

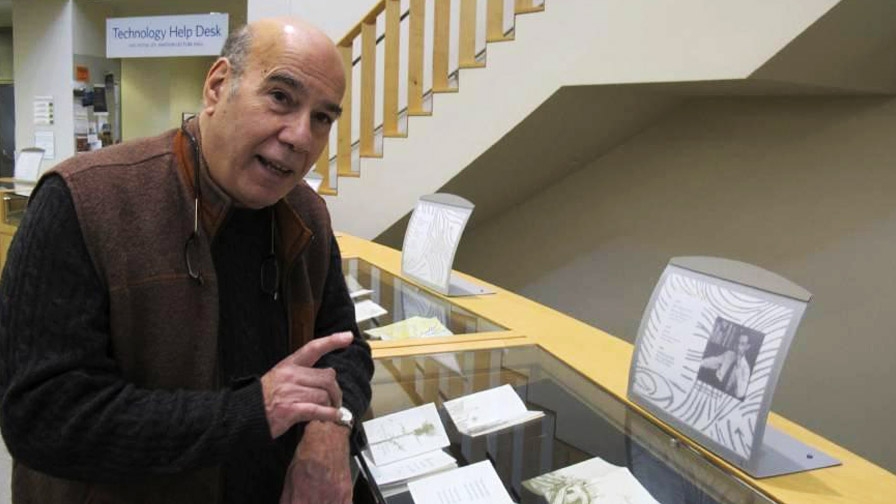

As the D. E. Axinn Professor of English and Creative Writing, Jay Parini is a force in the Middlebury College writing community. Since joining the English Department faculty in 1982, Parini has supported generations of students through writing workshops and courses. Parini has written more than 30 books, ranging from poetry collections and novels to biographical memoirs, such as his recent Borges and Me: An Encounter.

During his time at Middlebury, Parini has also served as an academic advisor and mentor for students. Devin McGrath-Conwell ’18.5 is one of those students, and he sat down with Parini for a wide-ranging discussion about literature, learning, and loving Vermont.

The following conversation has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

(Devin) Let’s start at the source. How did you find your love of literature?

(Jay) When I was 14 and 15, I used to wander into a library near my home in Scranton, Pennsylvania. There was a little old lady librarian named Mrs. Godfrey who kept feeding me books. She introduced me to Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Dickens, and a bunch of the first writers I ever read. So I’d say that she got me interested.

And then … I was writing. From high school on, I was writing a lot of poetry and occasional stories. Even some movie scripts, but I was just messing around with it. So, I’ve been working in different genres pretty much since I was in high school, and certainly in college I really got interested. So I’ve been reading and writing pretty much since the age of about 12 or 13.

Why do you think poetry was the first genre you gravitated to?

I remember reading Robert Frost when I was 15 for a class assignment, and I just absolutely fell in love with him. That made me think about the language of poetry, the music of it, the way poems lift off the page and stay in your brain. Prose is so amorphous. It doesn’t hit me as much as poetry does. It also helped early on that I went to church and listened to the poetry there. And reading the psalms and hearing them read. That kind of thing made a big impression on me.

Your mention of class assignments makes me wonder. Do you feel there were certain teachers, professors, or other mentors that guided your passion?

I’m insanely lucky with my mentors, going back to Mrs. Godfrey and two or three high school teachers who were just fabulous. Then in college, I had two or three teachers who were just as fabulous. I was lucky all along. I’ve always had mentors. So, one of the themes of my life is having mentors and being a mentor. They go together.

I’ve always understood that education, as they say, is a teacher on one end of a log and a student on the other end of a log. And that’s really all you need. Anything else is superfluous. The swimming pool, and the bubble where you can play tennis, and the football field, that’s all extraneous. All you need is the log and the student on one side and the teacher on the other and you’ve got your education. That’s the core.

Is that the nugget that drove you towards teaching as a profession?

Yes. The fact that I had some good teachers early on made me think, I want to do this. This is good. I like to talk to students. I mean, I still have mentors, believe it or not. I still talk to my old mentor from Scotland every week on the phone. He’s in his mid-80s now. So, that never ends. Well, it will certainly end at some point.

The big finish, as it were.

Yes. We do all get to the very end, but I’m still amazed that I’m in touch with my main mentor from Scotland, Tony Ash, all these years later. We talked on the phone for an hour yesterday!

Turning to Middlebury, what drew you here?

Well, first of all, I very much wanted to stay in New England because of my love of Robert Frost. And my love of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Those three figures were, in my early days, luminous, guiding writers in my head that I read over and over and over again. I reread Emerson’s essays endlessly. I reread Frost. I still do. I dreamed about Frost last night. I’m never too far from Robert Frost.

When I saw a job was available at Middlebury, I got very excited and applied for it, wanting to go here. And of course, over the years, I’ve stayed. Many times I’ve been tempted away. People have offered me jobs at other places. I could have, on various occasions, split and taken a job somewhere else, but I never wanted to leave Vermont. I want to be in this locale that feels comforting and inspiring to me. I like being around these woods and fields and mountains. So in the end, it’s the nature of New England that appealed to me.

Has your named professorship played any part in your staying at Middlebury?

Oh, I think so. At one point, when I really had some opportunities to go elsewhere, the Axinn chair, which has with it a stipend for travel and a reduction in course load, was just enough to tip the balance to make it possible for me to stay here. So the Axinn professorship has been huge in keeping me at Middlebury all these years.

I’ve always understood that education, as they say, is a teacher on one end of a log and a student on the other end of a log. And that’s really all you need.”

It must also be special because I know you and Don Axinn ’51 were quite close.

Well, that’s it, I mean, in fact, the Axinn Professorship was partly created through the work I did with Don Axinn and Bob Pack (former Middlebury English professor). I worked with Don in helping him to make the decision to fund the Axinn Center. We were playing tennis one day and it came up. He said, “What can I do for the College?” I said, “Why don’t you give us a new English Department?” So it all grew out of that conversation, and I worked with Don very closely. That was something I feel like I had a personal hand in. I was hardly the only one, but I was in contact with Don constantly. We talked on the phone every week till he died.

I’ll never forget, I was teaching the modern poetry class, maybe a year or two before Don died. In the middle of my class, Don walked into the room and I said to the class, “And here you are at the Axinn Center, and here is the Axinn.” Don thought that was very funny, and the students were quite amazed.

I’m glad you bring up class and students because obviously part of why I’m here is because I had the chance to take courses with you, be mentored by you, and become your friend.

Yes, you did.

I know that something I was able to do, and many students have been able to do, is take both analysis and workshop courses with you. The writing and the academic study. What is the importance of doing both of those?

Well, I just don’t approve of creative writing programs where you’re not studying literature as well. I think any writer worth his or her salt has to be a reader and a sophisticated reader. I don’t have any preference. I like teaching both literature classes and creative writing classes. I feel both of them inspire me. But especially, I want to get back to teaching Whitman and Emerson and Thoreau and Frost and W. H. Auden and T. S. Eliot.

I remember reading Eliot’s The Four Quartets with you and absolutely falling in love.

Oh, I love teaching The Four Quartets.

Remembering that course takes me back to your image of a teacher and a student on a log. The importance of mentorship in teaching for you. So, this far into your teaching and writing career, what keeps driving you to seek out those relationships?

Well, a mentor gets a lot back. You know what I mean? It’s a give and take. I mean, it’s not just delivering a lecture. You know, you’re in a relationship with the people you’re teaching, and it’s a two-way street. They’re teaching me as much as I’m teaching them. I have no sense of or belief in that the professor is superior. In any class, I consider myself a primus inter pares, first among equals. We’re all equal and we’re all just learning and reading. I’ve got more experience and I’ve been around a long time so I have some insights to add, but the students are often a lot smarter than I am. I’m very aware of that and grateful for being around students who have insights that surprise me continuously.

So, it keeps me awake. It’s all about being awake. And also it’s lovely. It’s wonderful to be present with people and for them to feel you and you to feel them. It’s why teaching has been very central to my life. It’s not something additional. Teaching is at the center of my writing life, ironically. People say, “How is it you can write and teach at the same time?” I don’t know how you do them separately. I mean, I don’t know how I would’ve written if I hadn’t been teaching all these years.

Of that writing life, we’ve talked about poetry, but I want to jump back and ask about some of the other forms. I never knew you played around with screenwriting as a teen, but I know especially in the last 15 to 20 years you’ve worked on a lot of screenwriting. In that form and beyond, what’s the draw to keep pushing into and experimenting with different genres?

It’s exciting to move into a new area and learn new stuff. And also, it’s all writing. You just apply your skills in different ways. I’m finished with writing straight biographies. I did Frost and John Steinbeck and William Faulkner and Gore Vidal. Those are straight biographies and they are extremely hard work, almost more than I could stand these days. Nowadays, I’d rather write novels about writers or write screenplays because I like the dramatic mode of screenplays. I’ve also come to really appreciate the collaborative aspect of screenwriting and moviemaking.

I had such a great time in 2017 on the set of the Gore Vidal movie with the director, Mike Hoffman, the producer, Andy Patterson, Michael Stuhlbarg, and the rest of the cast. We all became a family. We spent four months together on the set in Italy. I was behind the camera with the director for every single take. I learned a huge amount about how movies are made. This of course all came after working for 20 years on adapting The Last Station.

All this to say that since I’ve been producing movies as well as writing them, I’ve grown my understanding of how they’re made. I’ve been involved with figuring out how to raise the money with other producers I work with and I’m doing that right now. I’ve got three movies and two TV series in the works. I have one consistent cowriter and two I often work with as well. We work together on scripts and producing and so it’s terrific.

You used the phrase, “It’s all about being awake,” earlier on. Would it be fair to say that your teaching and writing lives are just one life of continued growth and learning?

Yeah, I don’t make a distinction. My students these days are very interested in narrative, in dramatic narrative. They’re all interested in movies, and TV series. That’s where a lot of the energy and the culture have gravitated toward. Therefore, it’s kind of exciting to work in areas where there’s a lot of interest. I’m able to talk to a lot of students about the work I do, and I think they benefit from being in touch with somebody who’s actually doing the stuff.

Oh absolutely.

Right? I mean, that’s good. The fact that I’m actually physically making movies and publishing novels and publishing poems is giving them something. They see how it’s done. They see how the sausage is made.

A full backstage pass to the logistics of a creative life.

And it’s often not pretty, but it’s a process.

Over the decades you’ve spent time with generations of Middlebury students. Is there anything that strikes you about the way that either the students in your courses or at the College, in general, have changed?

What stands out is that a college is not a static place. I think that Middlebury’s core thing is the student talking to the teacher and the teacher getting something from the student. The student and the teacher on the log. It’s an exchange going back and forth. Even in the classrooms, the classes are relatively small, but you talk to the students outside of class. I think most of my teaching has always been done outside of class. The actual classes are just the formal structure that allows you to have relationships outside of the class where you do the real teaching.

The hours you spend behind the desk in the classroom are minimal compared to the work you do talking to students in your office, in the coffee shop, in the streets, in the gym, whatever. It’s a continuous conversation you’re having. I just had a thousand-word email yesterday from a guy that graduated and did his thesis with me 25 years ago. He’s coming by for a cup of coffee next week and wants to talk about something he’s working on. So, I’m still in conversation with students over many, many years. They’re often sharing their work with me throughout a lifetime.

So my memory of Middlebury is my memory of interactions with particular students over the years. That is the core and anything else is just extraneous. I think Middlebury should never lose sight of the fact that this is its mission. This is where its values should lie. I mean, if anything, let’s get rid of the buildings and put a bunch of logs out in the field.

Well as someone who has been lucky enough to be on that log with you, I extend a heartfelt thank you from all of us who have been and will continue to be there.

I love being on that log. Of course, it’s metaphorical, but it’s also real. It’s the job, it’s the work. It’s the work of knowing and you learn in so many ways. It’s also the work of community. Middlebury is about community. We all know each other, we talk, it goes on and on. It really is amazing.