Movement Makers

Movement Makers

In 2008, eight of us, myself and seven Midd Kids, decided that we were going to organize the world to stop global warming.

How do you stop global warming?

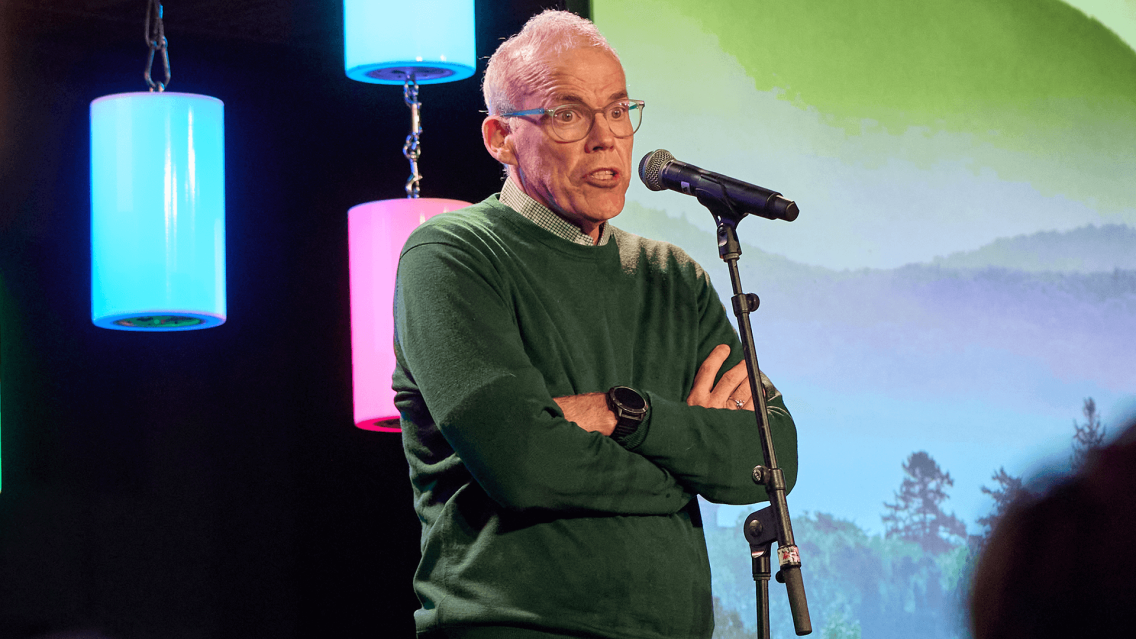

In 2008, environmentalist and Schumann Distinguished Scholar Bill McKibben and seven Middlebury students teamed up to organize the world to prevent further global warming. More than 5,000 demonstrations in 181 countries later, they had created a climate action movement together with young people of all races, nations, religions, and backgrounds. In the process, they had, McKibben says, realized that they were each “a small part of something large and beautiful and fragile that needs us.”

This past December, McKibben shared his story as part of the “Purpose and Place: Voices of Middlebury” event during the launch of For Every Future: The Campaign for Middlebury.

Watch McKibben’s talk above or read the transcript below.

Transcript

Where does change come from?

If you’re hanging out at, I don’t know, an elite liberal arts college in the northeastern United States, in that corridor where power and money reside, it’d be easy to conclude that change came from you or people like you.

And that’s not the worst thing in the world.

It provides a kind of obnoxious but useful self-confidence that can get you going.

In 2008, eight of us, myself and seven Midd Kids, decided that we were going to organize the world to stop global warming.

We formed a thing called 350.org, taking our name from what the scientists said was the most carbon you could safely have in the atmosphere, 350 parts per million, a number we’re well north of, which is why the poles are melting and the continents burning.

Um, but we went down into those long tables in the basement of the Grille and set to work figuring out how we were gonna pull off a Global Day of Action across the planet.

And as we began to fan out across the globe, we had some sense that this might be working.

I remember being in Bethlehem and trying to organize the three countries along the edge of the Dead Sea to work on this project.

There seemed to be a kind of unfilled ecological niche that maybe we had found, but we had no real idea if it was gonna work or not.

It seems to me that the sweetest fruit of a liberal arts education might be the recognition that in fact, we’re each a small part of something large and beautiful and fragile that needs us.

Remember, there were seven students here.

There are seven continents. Each one had taken one.

The guy who got the Antarctic got the Internet too, you know.

Um, we’d asked everybody to do this on a weekend, and on the Thursday prior, we were sitting around our little one-room office and the phone rang, and it was our volunteer leader in Ethiopia, who like most of us was a she, and like many of us was 17, and she was in tears.

She said, “The government has canceled our permit for Saturday.” Ethiopia not a very nice government all the time.

That wasn’t why she was in tears though. She said, “We’re doing this today before they can stop us. And we’re really sorry because we wanted to do it the same time as everybody else. We wanted to be part of the whole world. We hope we’re not spoiling it for everybody.”

And then amidst the tears, she, almost as an aside, said, “And there are 10,000 students right now out in the street in Addis Ababa chanting 350.” And we looked at each other in disbelief: 10,000.

And someone said, “Luo, don’t worry about the date. You are amazing. We just need a picture of this so we can get it out around the world.”

And she said, “Oh, the Internet’s not working really today.”

Good. This was 2009, and this was one of the poorest places in the world.

So I did some quick Googling and I said, “Luo, there’s a one Western hotel in Addis, the Intercontinental, and they’ve got Wi-Fi in the lobby, and if you walk in there, you can use that and send us this picture, which we really need.”

She said OK. And we sat back and then about 20 minutes later, the phone rang again and she said, “Uh, that hotel is not, that hotel is for visitors. That hotel is only for white people.” And we looked at each other again in a kind of disbelief.

But we needed the picture. And I said, “Luo, find some nice-looking white lady who’s walking in the door and hand her your phone and tell her to press the button when she gets in there.”

And that’s what she did. And three minutes later, we had that picture, and 10 minutes after that, we had it out all over the planet to journalists, everywhere.

It was the kind of proof we needed that this was real, and they were gonna have to cover it.

Luo was kind of a harbinger. When the weekend proper came, 48 hours later, pictures started flooding in from all over the world.

From Maasai country in Kenya, from the Andes, from the Himalayas, from Delhi, from Dharamsala, from Beijing, from Burlington.

Before we were done, there had been 5,100 demonstrations in 181 countries.

CNN said it was the most widespread day of political action in the planet’s history.

Now, my job that day was to collate those photos as they came in.

This was before Facebook. Our killer app was something called Flickr.

And these pictures were coming in 10 and 20 a minute sometimes, you know.

And as I looked at them, I realized that Luo was not an exception.

If we taught the world a little bit that weekend about climate, we’d learned a lot about power and challenge and real courage.

I’d spent my life having people tell me that environmentalism was something that rich white people did. And if you didn’t know where your next meal was coming from, you wouldn’t be an environmentalist because you had more pressing concerns.

And it took about 20 minutes of watching those pictures flood in to realize that that was nonsense.

That most of the people we were working with around the world were poor and Black and brown and Asian, and young, because that’s what almost everybody on this planet is.

And they were exactly as concerned about the future as those of us back in that little room in Middlebury, maybe more so because the future bears down hard on you in those places.

Now, we were proud of what we’d done.

I mean, I was over the moon when those pictures came in, and I saw, from the beach in Jordan, thousands of people forming a giant human 3, and from the beach in Palestine, the giant 5, and hundreds and hundreds of Israelis making the zero on their beach.

Those seven kids, now grown with kids of their own, have all gone on to be climate leaders.

But I think none of us have any real confusion anymore about where change comes from.

If we taught the world a little bit that weekend about climate, we’d learned a lot about power and challenge and real courage.

That picture from Ethiopia’s been by my desk ever since.

The world, especially at its elite end, our culture, spends a lot of time trying to convince you that you’re the most important person on the planet, the heaviest object in the known universe around which all else should orbit.

It seems to me that the sweetest fruit of a liberal arts education might be the recognition that in fact, we’re each a small part of something large and beautiful and fragile that needs us.

Thank you.