Building Belonging

Building Belonging

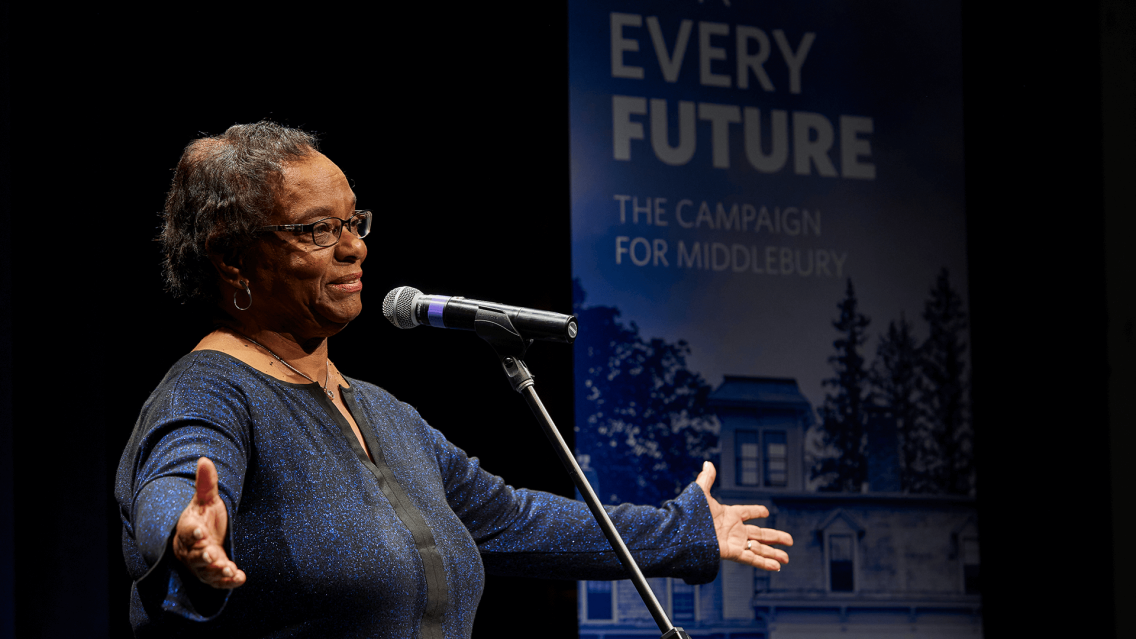

“I decided if I was gonna stay here, then here was gonna be better for me and others. So I started using my voice and I encouraged other people to use their voice.”

Mildred Reese McNeill ’74 started college as part of the then-largest cohort of Black students at Middlebury: 16 people. They would create many firsts at Middlebury and lay the foundation for future BIPOC students.

Watch Reese McNeill’s talk above or read the transcript below.

Transcript

When my class came to Middlebury in 1970, many of us had been touched by the Civil Rights Movement.

Middlebury’s administration from the president down had decided that year that they would enroll the largest class of Black students that they had ever had, and they did—16 of us.

I don’t really have a problem with that number because before that, and since then, I’ve often been the only one who looks like me in various places.

But Middlebury did worry about how we would feel.

So they brought us to campus two weeks early so we could meet each other, we could find our way around campus, we could take some sample classes. And they also had appointed Arnold McKinney [Class of 1970] as a dean.

We called him the Black dean and, and he was the person that we could always go to for guidance and support.

We actually formed a cohort, and they made us feel comfortable here.

Comfort was an important thing for me because I did not have that in my high school years.

The year I moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, to start high school was the year that they had closed the Black high school and were sending all of us to the formerly white high school.

Every day in homeroom, we had discussions about race and our feelings.

I was the only Black person in my homeroom.

I remember particularly the day that there was this big strapping football player literally sobbing because we all shared the same cafeteria. And his father had told him to never eat with N-words.

One of my biggest dreams for high school was to be a cheerleader.

So when they announced the cheerleading tryouts, I went to the room that they said would be where the tryouts were.

Then I went to the gym, then I went to the office to check.

Then I just kept opening classroom doors. I never found those tryouts.

When my father picked me up, I told them they must have decided not to have cheerleaders this year. And that’s what I expected to see when I went to the football game.

But there they were, the all-white cheerleading squad cheering away.

Incidents like that caused me to never feel comfortable at my high school.

But at Middlebury, things seemed to be different.

I found the tryouts. I convinced my cohort classmate Stephanie Palmer to try out with me.

We made the squad, and being a cheerleader was everything I dreamed it would be. But there still were things here that made me feel out of place.

I came to Middlebury because of the Language Schools, but my French teacher did not like me.

I don’t know if it was my Southern drawl or what, but every time I said something in class, she screeched that she could not understand anything that I was saying.

And then there was religion class. Every paper I got a C. No corrections, no comments. Just C.

So I went to see the professor and he looked at me and said, “I thought you’d be satisfied with a C.”

What did that mean? Did he think I was at Middlebury to be given a degree and not earn one?

I began to wonder whether faculty were not on the same wavelength as the administration.

Did they have a feeling when they looked out at a class and saw one of the 16 that we didn’t deserve to be here, and did they ever think what it was like to be one Black student in a classroom of 20 to as many as a hundred white students?

And then it snowed.

I was sitting in my room looking out the window.

My junior counselor came by and said, “Don’t you have class?”

I said, “It’s snowing.”

She said, “Yes, but you have to go to class.”

I said, “Look out there. When they walk, their footprints fill in. How do we get food?”

By now, she’s laughing so hard, she can hardly talk.

She said, “Proctor is open, and you have to go to class.”

Well, I still was not convinced that professors would know how to drive in this, but I had a bigger dilemma.

I had spent the whole summer making cute little cotton dresses for college, and my boots were go-go boots.

Picture it.

So despite people’s best efforts, I was unhappy. I felt isolated, and I was cold.

I started thinking about transferring, but then I found out that my family were gonna move from Charlotte to the Philadelphia area the coming summer.

So there really wouldn’t be a home for me to go to. Decision time.

I decided if I was gonna stay here, then here was gonna be better for me and others.

So I started using my voice and I encouraged other people to use their voice.

We started the Black Student Union. I was elected president, and we got some changes made. We started an African dance troupe, a Black theater group. We performed on campus and off campus. We got the campus store to carry Black hair products, big deal. And I encouraged more of my sisters to try out for cheerleading. And by junior year, we had an all-Black squad, but there were things that were still missing.

There wasn’t this real feeling of belonging.

And we felt that we needed a place on campus where we could just go and be ourselves, not always just having to represent.

In 1972, the College gave us a space.

It was the annex of Adirondack House, one of the oldest buildings on campus.

And I believe nobody had unlocked that door for 50 years.

It was dark, it was dirty, and it was peeling everywhere, including the floor.

But it was our space. Every day between classes, at night, on the weekend, we were in there cleaning and scraping and painting and fixing it up.

And we were talking about how we were gonna use it.

Of course, we were gonna have parties, but we also were gonna have programs. And we planned to have debates with the professors who taught things like slavery was good for the slaves and other outrageous information.

But we were gonna chill, play music, and finally have a place to be ourselves.

When you walk into the annex, on the right hand side was a floor-to-ceiling fireplace made of stone. When we cleaned it up, it was beautiful.

We had decorated the room with the red, black, and green liberation flag and posters of all the civil rights icons all around.

Then came the night of our first official BSU meeting in our space.

There were about 40 of us by then, and people gathered ceremoniously around the fireplace.

Some were sitting in chairs, some were sitting on the floor, some were leaning on each other, but everybody was comfortable.

Our first order of business was to name our space.

We threw out the usual names, you know Davis, King, Baldwin, but you remember the Black Dean Arnold was a huge jazz aficionado.

He said, “You know, jazz is an American music genre with world overtones. This group is made up of Black students from the United States, from Africa, and from the Caribbean. I think jazz is symbolic of who this group is, and I think that we should name this after John Coltrane.”

So that is how Coltrane Lounge, Middlebury’s first Black cultural center, came to be.

Middlebury remained cold to me temperature-wise, but I did develop a warmth and a sense of purpose here.

I still stay in touch with some of my cohort, and I actually married one. But I am most proud of the fact that we, the 16, were not an experiment.

We became a foundation for the future of Black students at Middlebury.

And for that, I give a cheer.