Summer Neuroscience Research Brings Students New Techniques and Deeper Knowledge

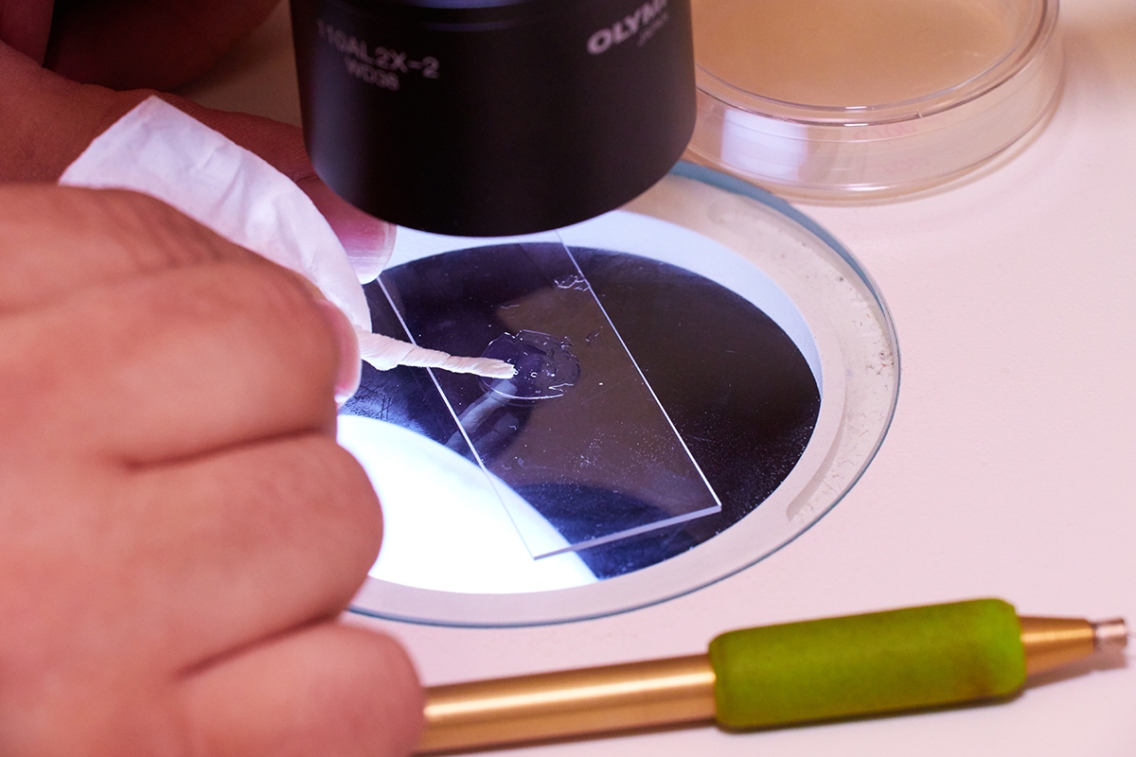

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – Working under a microscope, summer research assistant Jessica Guo ’21 demonstrates a critical skill in biology and neuroscience professor Glen Ernstrom’s lab.

Worm picking.

Ernstrom’s research uses the microscopic Caenorhabditis elegans, a roundworm in the same family as hookworms and pinworms.

Edith Lopez ’22, left, and Jessica Guo ’21 are summer research assistants in biology professor Glen Ernstrom’s lab at McCardell Bicentennial Hall.

Ernstrom uses C. elegans to better understand neurotransmitters—the chemicals that play an important role in how neurons (nerve cells) communicate with each other and with other kinds of cells throughout the body. Problems with neurotransmission are linked to such diseases as depression, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s, seizure disorders, and a host of others.

“By studying the basic biology of chemical neurotransmission,” said Ernstrom, “we seek to understand some of the defining characteristics of neurons, and our findings may lead to improved therapies to treat neural disorders.”

His research focuses on the protein enzyme V-ATPase and its role in neurotransmission. Among this summer’s questions: Where is V-ATPase found throughout the worm’s body? Just in neurons? Or also in other kinds of cells? Which neurotransmitters does it regulate? What is its role in the neurotransmission process? What, especially, is its role in the release of neurotransmitters at the synapse (neuron cell junctions)?

Ernstrom describes the loading and release of neurotransmitters from one neuron to the next as something like filling up water balloons and smashing them against a wall.

To track V-ATPase in the worms’ bodies, Ernstrom uses “molecular, genetic methods” to tag it with something called green fluorescent protein (GFP), first derived from jellyfish by one of Ernstrom’s graduate professors (and for which he co-won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry).

“The process of making worms glow in the dark is one of the main approaches we use to probe the biology of nerve signaling,” Ernstrom said.

Seen under a high-powered microscope, each GFP-tagged protein lights up throughout the worm’s body, highlighting its place along the nervous system from the “nerve ring” encircling the worm’s head, threading down the major ventral (abdominal side) nerve cord and delicately threading toward the smaller nerve cord running along the worm’s “back.”

One of biology professor Glen Ernstrom’s student research assistants creates a slide with the microscopic C. elegans worms.

Because the animal is alive, it’s like watching a green-glowing constellation snaking its way across the night sky. The sight is awe-inspiring and just plain beautiful.

C. elegans is the model organism of choice for many scientific researchers. They’re also just plain cool.

They’re transparent.

“These animals have see-through skin: you can easily see all of their inner workings under the microscope as they behave,” Ernstrom said.

They’re ancient. Scientists now consider nematodes to be among the oldest life forms on earth—emerging right after bacteria, protozoa, and fungi.

And, quite humblingly, they’re enough like us to make them a perfect research subject for unlocking the mysteries of the human brain and human nervous system.

“Just like us, they have the same chemical neurotransmitters and share the same basic cell structures that allow their neurons to release chemicals.”

Ernstrom smiles when he shares one of C. elegans researchers’ favorite quips from Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra: “You have made your way from worm to man, but much within you is still worm.”

A highlight thus far for both Guo and Lopez was accompanying Ernstrom to the the 22nd International C. Elegans Conference and learning about cutting-edge research worldwide.

“There were a thousand-plus people there, and they were all super into worms,” said Guo, a rising junior. “It’s a really tight-knit community. We got to see all the research that everyone was doing and see how our research is related. We would go to talks and poster sessions and then have lunch, and Professor Ernstrom would be like, ‘Oh, I have so many new ideas. And what did you guys see that was interesting?’”

Guo and Lopez also enjoy the camaraderie of the lab and the chance to work more closely with one of their professors.

“In high school you develop a relationship with your teachers, but you’re still a student,” said Lopez. “Being able to work with Ernstrom as a colleague is a different experience.”

Assistant Professor of Biology Glen Ernstrom looks at microscope images of the worm C. elegans with summer research assistants Edith Lopez ’22 and Jessica Guo ’21.

Ernstrom said that among the many forces that drew him to a life in science was “a long line of incredible, inspiring teachers,” starting with high school biology.

“Dr. Pike Messenger. He had red, scruffy hair, this thick Boston accent, and he was kind of no nonsense, right? Dr. Messenger was amazing for many reasons—his enthusiasm, his way of speaking. He told stories. He integrated art and culture and history. He’d give a college-level lecture—I was just in ninth grade.”

“My town is right near the ocean, and he’d go out early in the morning and bring back buckets of specimens, day after day. If we were learning about small invertebrates, he’d bring back a whole bunch of crabs and things like that or certain plant species. And we would sit and characterize them, draw them, try to understand differences. For a kid growing up in the suburbs, it was like, ‘Wow, there is a whole world sitting right outside my door.’”

“I just loved it. I was hooked.”

As an undergraduate and graduate student, Ernstrom said he continued to be “at the right place at the right time,” working alongside leading scientists who were also great teachers.

Central to his love of teaching is offering that same opportunity.

“I like the excitement that comes with introducing people to a whole new world. That’s part of it,” said Ernstrom.

“During the summer, of course, I get to know the students really well. Not just their interest in science but what makes them tick. What are their motivations? Their aspirations? Their sense of humor? How do they perceive the world? That’s the fuel that keeps me going as a teacher and a researcher. By interacting with students, I get to see the world from a different perspective and that opens up my world.”

One of his greatest satisfactions as a mentor, Ernstrom said, is watching students transform from hard-working beginners—mastering basic concepts, terminology, and techniques; eager to get it right; sometimes frustrated but learning from failure; “wide-eyed and a little nervous”—to “real, genuine, critically thinking scholars.”

Continued Ernstrom: “I know my job is done as a college professor and mentor when a student starts arguing with me, when I have an interpretation of the data and they say, ‘No, my interpretation is this because of x, y, z.’ And I’m like, ‘Yes!’ I jump for joy—because that’s where new knowledge is forged.”

By Gaen Murphree; photos by Todd Balfour