African-American Portrait Photography in the Spotlight

Many Thousand Gone: Portraits of the African-American Experience

May 22–August 9, 2015

For immediate release: 2/26/15

For further information contact: Emmie Donadio, Chief Curator, at donadio@middlebury.edu or (802) 443-2240

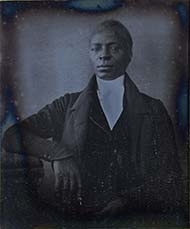

Middlebury, VT—On May 22 the Middlebury College Museum of Art will open the next installment in a growing tradition of museum exhibitions generated via the scholarship of Middlebury College students in their course work. Many Thousand Gone: Portraits of the African-American Experience, 1840–1965, an exhibition co-curated by Associate Professor of History William Hart and the students in his Spring 2015 “African-American History” course, consists of nearly 100 photographs generously loaned to the museum by George R. Rinhart, a private collector, of Palm Springs, CA. The exhibit takes its title from a sorrow song dating from the Civil War sung by black Union soldiers and freedmen and –women. The lyrics to its opening stanza are:

No more auction block for me,

No more, no more;

No more auction block for me;

Many thousand gone.

Each stanza begins with the repeated rejection of a brutal practice inflicted upon the enslaved: “No more peck of corn for me”; “No more pint o’ salt for me”; “No more hundred lash for me.” Each stanza then concludes with the refrain “Many thousand gone.”

Initially, “many thousand gone” referred to the thousands of enslaved individuals who escaped to the northern states during the mid-nineteenth century. Over time, however, the expression embraced myriad thousands, including the hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans and African-Americans who never experienced the joys of freedom, and the thousands who fought on the front lines of the Civil Rights struggle. The photographic portraits of African Americans in this exhibition, assembled together for the first time, pay homage to all those many thousands gone.

Historians of photography remind us that photographs carry meaning. They literally frame a moment in the past, and thus, connect the past to the present through us, the viewer. When we look at a photograph, we are invited to imagine the past. This guiding principle has informed the process through which the students in the course have approached the organization of the exhibit. Each student has selected a photograph to research and will explain the meaning and significance of that photograph to the African-American past thus deepening the students’ knowledge of African-American history and affording them a significant voice in the curatorial process.

The images in this exhibition represent a small fraction of Rinhart’s little-known vast and rich photographic collection. Some of the photographers from his collection featured in this show include J. A. Palmer, known for his images of black southern life during the era of Reconstruction (1865–1877); Myron H. Kimball, a New York photographer who photographed mixed-race emancipated children from New Orleans; Civil-War photographers James F. Gibson, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Alexander Gardner; Herbert Gehr, whose photographs depicted black life in 1940s Harlem; myriad anonymous photographers who snapped pictures between the late-nineteenth century and the 1960s for the large photographic firm of Underwood and Underwood; Carl Van Vechten, the renowned white fixture of what was known as the Harlem Renaissance, who photographed famous black artists, writers, and entertainers of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s; Flip Schulke, well-known for documenting the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s; and Charlotte Brooks and Margaret Bourke-White, the only women staff photographers for Look and Life magazines respectively.

The photographs in the exhibition cover more than 125 years of black life in the United Sates. They begin with portraits of free blacks in the North and enslaved blacks in the South in the 1840s and 1850s. The 1850s was arguably the bleakest decade of the nineteenth century for free and enslaved African Americans. Several federal and state court decisions restricted the rights and options of free and enslaved African Americans as the nation fractured under the strain of expanding slavery to the new territories. In 1861, irreconcilable differences and the election of President Lincoln split the nation in two. Several photographs in this exhibition capture black participation in the Civil War, both as soldiers and as contraband, as well as document the impact of the war on black southern civilians, many of whom were forced to relocate. Post-war Reconstruction, the Republican Party’s strategy to bring the Confederate states back into the Union without slavery and with the official recognition of former slaves as now free and independent citizens, gave rise to a variety of photographs that interpret variously ordinary black life. Portraits of black sharecropper families, of black children living in grinding poverty, of African Americans posed in minstrel-like settings both empathize with and ridicule free blacks. With the end of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow, intimidation of African Americans accompanied ridicule. Here we see photographs capturing vigilante justice (lynchings) as well as depicting the harsh treatment of black prisoners.

African Americans have been largely a patriotic folk. They have answered the call of military service in every American war dating back to the American Revolution. Several photographs reveal African-American parades commemorating Armistice Day (World War I), training for World War II, and black officers relaxing at segregated officers’ clubs. In between the two world wars, African-American popular culture enjoyed an awakening. At this time, several artists came to prominence, including Bessie Smith, Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, James Weldon Johnson, and Ethel Waters, to name a few. Carl Van Vechten, whom Zora Neal Hurston called a white “Negrotarian,” photographed the veritable “Who’s Who” of black arts and entertainment of this era. Concomitantly, African Americans strove to go about their daily lives quietly, shopping at local department stores, worshipping at the church of their choice, and listening to black politicians and preachers. Meanwhile, from time to time, a growing number of African Americans protested acts of injustice and discrimination through individual acts of defiance and through peaceful group action. A number of photographs on display capture movingly the courage, the commitment, and the dedication of the many thousands who battled on the front lines of the Civil Rights movement.

With such a broad range of images, many of which have rarely or never been shown publicly, this exhibit offers an uncommon opportunity to glimpse the spirit of the exhaustive Rinhart collection and to contemplate the many faces and facets of more than a century of the African-American experience. Many Thousand Gone will remain on view in the museum’s Christian A. Johnson Memorial Gallery through August 9.

The Middlebury College Museum of Art, located in the Mahaney Center for the Arts on Rte. 30 on the southern edge of campus, is free and open to the public Tues. through Fri. from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sat. and Sun. from noon to 5 p.m. It is closed Mondays. The museum is physically accessible. Parking is available in the Mahaney Center for the Arts parking lot. For further information and to confirm dates and times of scheduled events, please call (802) 443–5007 or TTY (802) 443–3155, or visit the museum’s website at museum.middlebury.edu.