All Hail the Acropolis!

Untouched by Time: The Athenian Acropolis from Pericles to Parr

January 10–April 23, 2017

For immediate release: 1/10/17

For further information contact: Pieter Broucke, Associate Curator of Ancient Art, at broucke@middlebury.edu or (802) 443-5227

Middlebury, VT—On Tuesday, January 10 the Middlebury College Museum of Art opens Untouched by Time: The Athenian Acropolis from Pericles to Parr, an exhibition that explores our culture’s centuries-old obsession with the monumental ruins of the Athenian Acropolis.

The Enduring Fascination of the Athenian Acropolis

The building program on the Athenian Acropolis, constructed during the second half of the fifth century BCE under the stewardship of the Athenian statesman Pericles, has come to be the most celebrated architectural expression of the High-Classical era. Writing some five hundred years after it was completed, the Roman historian Plutarch (45–120 CE) commented:

“It is this, above all, which makes Pericles’ works an object of wonder to us—the fact that they were created in so short a span, and yet for all time. […] A bloom of eternal freshness hovers over these works of his and has preserved them from the touch of time, as if some unfading spirit of youth, some ageless spirit had been breathed into them.”

Indeed, Plutarch’s stunning assessment of the Periclean building program on the Acropolis remains as apt today as it was two thousand years ago. Yet, while the impact of the “Golden Age of Pericles” on Roman civilization is both seamless and strong, the post-medieval West had to wait until the Enlightenment Period (c. 1750 onwards) before political conditions in the eastern Mediterranean and a renewed desire to reconnect directly with Greek Antiquity would see Western artists and architects flock to Athens.

Since that time visitors have measured, drawn, painted, photographed, interpreted, admired, and even danced upon the antiquities of Athens, with each cultural epoch bringing its own aesthetic, technological, and even economic sensibility to bear upon how the notion of the classical as expressed by the Periclean Acropolis has been perceived.

Untouched by Time—which brings together early archaeological publications, paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, reconstruction images, and books all drawn from collections at Middlebury—chronicles the changing perceptions of the Acropolis over the last three centuries and bears testimony to the ever enduring fascination with these monuments.

Early Travelers: Antiquarians, Architects, and Artists on the Acropolis

During the eighteenth century a debate raged among antiquarians regarding whether Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome was the “true fountainhead” of Western civilization. When the Greek side prevailed, antiquarians such as Englishmen James Stuart (1717–1788) and Nicholas Revett (1720–1804) turned their attention to Greece and traveled there to study and document the ancient Greek remains, particularly the ruins on the Acropolis. When in 1762 Stuart and Revett began to publish their four-volume Antiquities of Athens, several pages of which are reproduced in the exhibit, they quickly sparked further interest among antiquarians, architects, and artists, many of whom found their way to Greece in the following decades.

The drawings, paintings, and publications of these early travelers—works such as Charles Lock Eastlake’s View of the Erechtheum on the Acropolis, and Sanford Gifford’s The Parthenon, May 10, 1869—renewed Westerners’ taste for the antique and led directly to Greek Revival architecture in Western Europe and North America. It also caused a groundswell of support for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire, achieved in 1830.

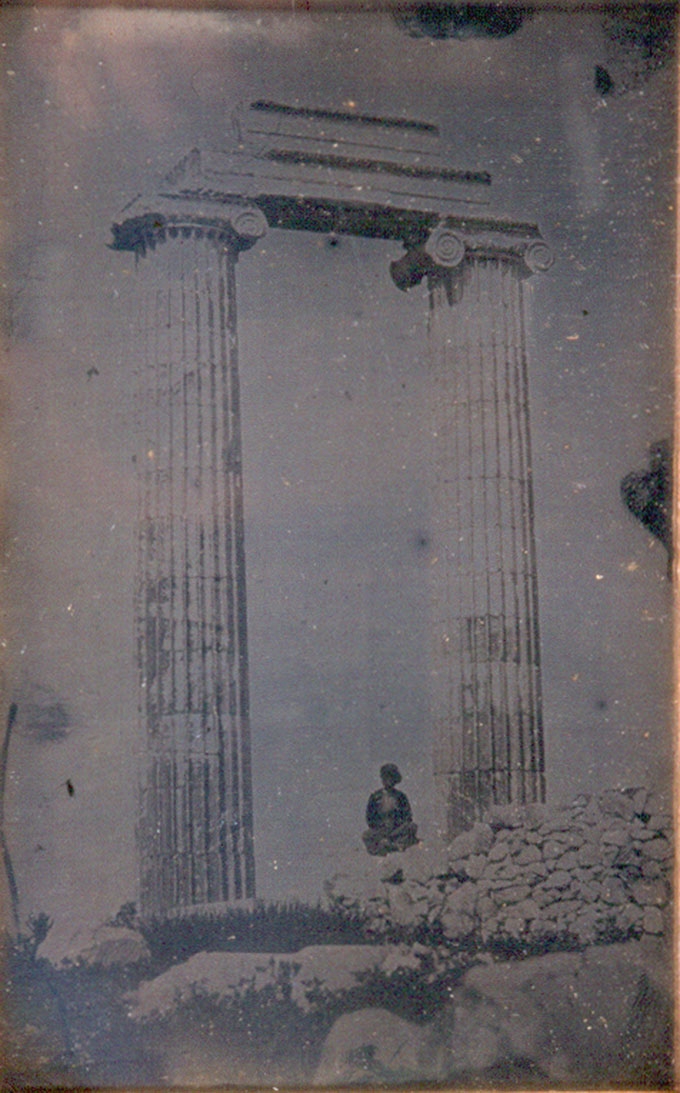

Early Photography and Tourism

Within a decade of Greek Independence, the invention of the daguerreotype and the birth of photography brought a wave of artists and travelers from around the world to focus their lenses on the picturesque sites of Greece. Some explored broadly, such as French photographer Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, who recorded multiple images of the large Hellenistic Temple of Apollo at Didyma in Asia Minor. Others, such as Eugéne Piot and William Stillman, favored Athens, and the Acropolis itself. Stillman produced a folio-sized volume of 25 views of the Acropolis, several of which are featured in the exhibit.

As travel to Greece became more and more popular, tourists, looking to document their visits, acquired images from local photographers and later gathered them in travel albums, compiled as keepsakes. Stereoscopic views provided early “virtual reality” experiences, albeit in black-and-white. After 1888, when George Eastman marketed the first snapshot camera, tourists began to capture their own images as photographic souvenirs. Photographers such as Dimitrios Konstantinou and Petros Moraites catered specifically to the growing tourist crowds and produced views of the Acropolis that were particularly popular with both tourists and later photographers. The exhibit includes travel album images by Konstantinou, Moraites, and other photographers, as well as anonymous images of visitors to the Acropolis.

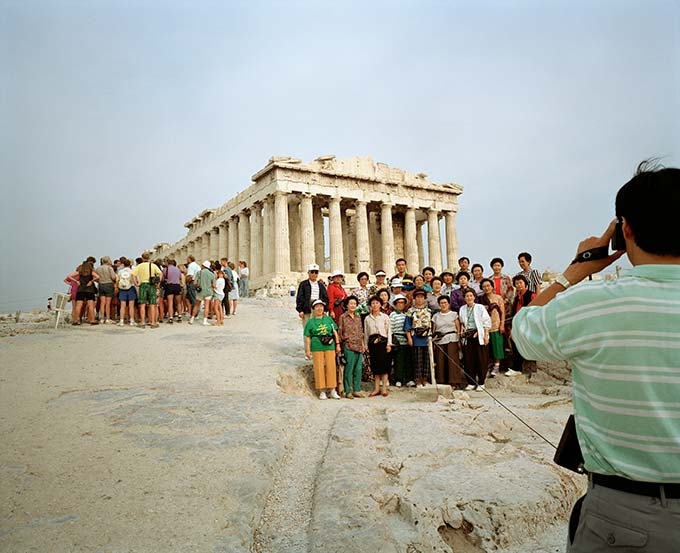

A Constant Source of inspiration: Modernism

The crisp forms of the Acropolis ruins have remained a profound source of inspiration for creative individuals through the twentieth century and beyond. Architects such as Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn both were deeply informed by classical antiquity. A pastel drawing by Kahn beautifully captures the warm hues of Greek marble set against the bright Mediterranean sky and bears witness to his formative process of discovery and transformation. An Edward Steichen photograph captures Isadora Duncan, the founder of modern dance, as she strikes a commanding and expansive pose in front of the portico of the Parthenon. And an image by Martin Parr, a British photographer known for documenting the absurdities of human behavior, captures tourists crowding into a group portrait in front of the Parthenon.

The Acropolis Restoration Project, 1975–2002

In 1975, after nearly two centuries of well-intended restorations undertaken by Greeks and foreigners alike, a committee was established to supervise the comprehensive conservation and restoration of all the buildings on the Athenian Acropolis. Since then, a team of Greek archaeologists, architects, engineers, and other experts have documented, dismantled, consolidated, restored, and re-erected the High Classical monuments.

Guided by the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments, the restoration project is one of the largest and most innovative of its kind. Its interventions are based on the principle of reversibility of preservation and reconstruction, as well as on a respect for the history of the structures throughout all phases of their survival—not just their antiquity.

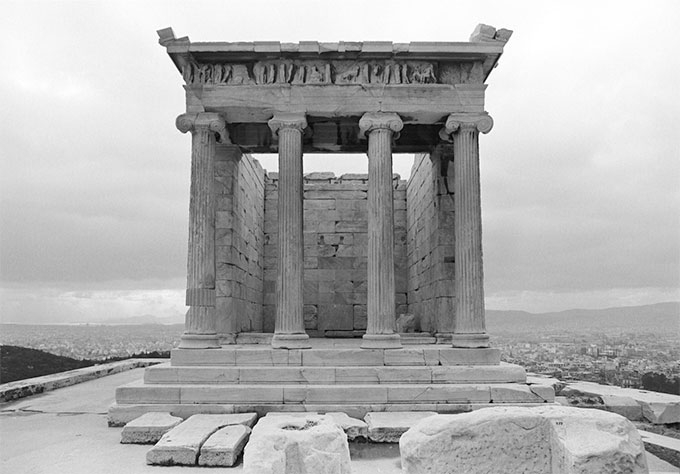

This heroic undertaking was meticulously documented by Socratis Mavrommatis, head of the photographic department of the Acropolis Restoration Service. His stunning images, nine of which are on display in the exhibit, show the buildings before, during, and after the interventions. Taken together, they bear testimony not only to the scale and impact of the project on the Periclean monuments but also to the photographer’s keen eye and elegant objectivity as a documentary artist.

The Acropolis, Globalization, and Mass Tourism

Today the Acropolis, splendidly restored and partially reconstructed, is a must-see destination for any tourist visiting Europe. Freewheeling back-packers and package-deal tourist groups alike alight on the “Sacred Rock” to experience firsthand the Periclean monuments. While some may merely check it off their “to do” lists, most are profoundly touched by the spectacle of history, gleaming marble, blue sky, and brilliant light.

As with other tourist destinations, crowd control at the Acropolis has become a major enterprise. Especially during the summer months visitors are expeditiously kept on designated pathways. Entering any of the ancient structures is now severely restricted, as are the nighttime full-moon visits of yore. In 2000, before the 2004 Athens Olympics, the Acropolis museum was moved to a new and much larger site nearby.

As a whole, the Acropolis does more than bear testimony to the greatness of Periclean Athens of the fifth century BCE. It has become the iconic monument associated with Greece as a modern nation state. On a loftier level, it marks the birthplace of Western civilization and serves as the global symbol of democracy.

Thus the Acropolis continues to inspire.

Related Events

[view:events==228211/1651] [view:events==228213/1653]

Press Images

Sanford Robinson Gifford (American, 1823–1880), The Parthenon, May 10, 1869, oil on canvas, 6 5/8 x 11 5/8 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by the Christian A. Johnson Memorial Art Acquisition Fund, 2016.102.

Charles Lock Eastlake (British, 1793–1865), A View of the Erechtheum on the Acropolis, Athens, 1818, oil on paper laid on canvas, 18 1/4 x 21 1/2 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Gift (by exchange) of Wilson Farnsworth, George Mead, and Henry Sheldon, 2015.020.

Louis Kahn (American, born Estonia, 1901–1974), Propylaia, Acropolis, Athens, Greece, 1951, pastel on paper, 11 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Purchase with funds provided by the Walter Cerf Art Fund, 2011.020.

Martin Parr (British, born 1951), GREECE, Athens, Acropolis from the series Small World, 1991, archival pigment print, 20 x 24 inches. Edition of 25. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Gift (by exchange) of Wilson Farnsworth, George Mead, and Henry Sheldon, 2015.227.

William James Stillman (American, 1828–1901), The Erechtheum, Plate 19 from The Acropolis of Athens, 1869/70, carbon print, 8 1/2 x 7 1/4 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Gift (by exchange) of Wilson Farnsworth, George Mead, and Henry Sheldon, 2015.026.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892), 76. Jéronda. Temple—Colonnes. [Didyma], c. 1843, daguerreotype, 7 3/8 x 4 3/4 x 5/16 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Purchase with funds provided by the Christian A. Johnson Memorial Art Acquisition Fund, 2004.034.

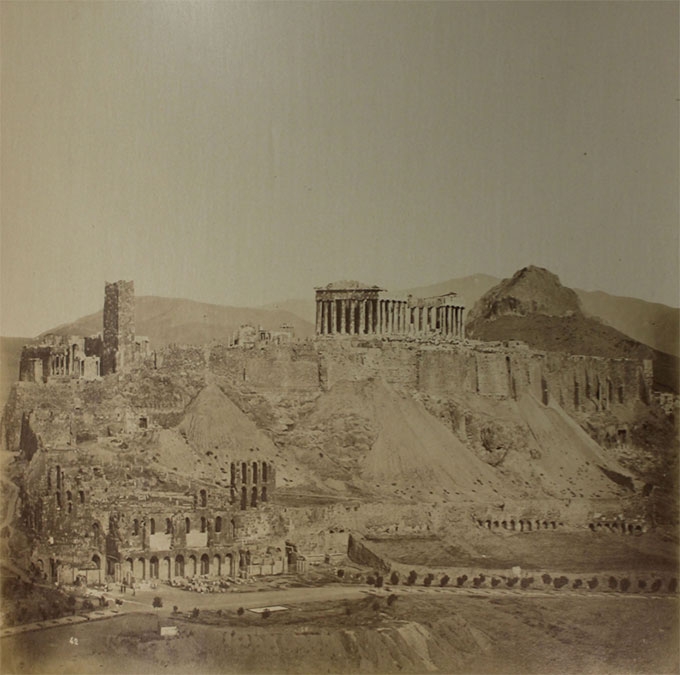

Dimitrios Konstantinou (Greek, active 1858-1860s), General view of the Athenian Acropolis and the South Slope from the southwest, c. 1860-65, albumen print, 11 x 14 1/16 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by the Fine Arts Acquisition Fund, 2013.019.59.

Anonymous (possibly American, active c. 1900), Snapshot of a tourist family in front of the Erechtheion’s Caryatid Porch, c. 1894–1902. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Gift of an anonymous donor, 2004.038.

Socratis Mavrommatis (Greek, born 1949), Parthenon. Beginning of the restoration works. Dismantling of the northeast sima, 1986, archival pigment print on paper. Image, courtesy of the Acropolis Restoration Service.