College Museum Confronts Race and History

“Confronting History: Contemporary Artists Envision the Past”

February 13–April 19, 2008

For immediate release: 11/20/08

For further information contact: Emmie Donadio, (802) 443–2240

Middlebury, VT—On Fri., Feb. 13 the Middlebury College Museum of Art opens the exhibition Confronting History: Contemporary Artists Envision the Past. Organized around the gift to the museum of Kara Walker’s 2005 Harper’s Illustrated History of the Civil War (Annotated), a portfolio of 15 offset lithographs and silk screen prints donated by Richard and Kathy Fuld (Middlebury Parents, 2003 and 2007), the exhibition features artists who use the print medium to revisit and reinterpret historical conflicts. The works on view, all based on printed sources that the artists readily acknowledge, demonstrate a rich mix of contemporary printmaking strategies and techniques. Many address themselves to the issue of race, and the exhibition explores that general topic in historical perspective, ranging from the Age of Enlightenment to the present day.

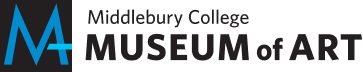

Kara Walker, Confederate Prisoners Being Conducted from Jonesborough to Atlanta from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005, offset lithography/silkscreen, image size 24 x 35 inches, paper size 39 x 53 inches, edition of 35. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont. Gift of Kathy and Richard S. Fuld, Jr. Image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

In addition to Walker, the prominent artists represented are Enrique Chagoya, Ellen Gallagher, Robert Gober, Glenn Ligon, William Kentridge, and Adrian Piper.

Walker’s suite appropriates 15 woodcut illustrations from Harper’s Weekly, the nineteenth-century magazine that covered the progress of the Civil War for a mass circulation. Upon the much enlarged originals, which have been reproduced through offset lithography, Walker has superimposed the signature black silhouettes that are the wellspring and trademark of her original style. Such figures are best known in the room-scale, over-lifesize installations that comprised her recent retrospective exhibition “Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love.” The exhibition, organized by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, traveled to the Whitney Museum in New York and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Walker’s “annotations” bring the unmistakable stamp of the artist’s presence to bear upon the record of this conflict. As such, they demonstrate what she has referred to as the “landscapes that exist in the back” of her “more austere wall pieces.”

Like Walker’s work, Glenn Ligon’s “Runaways” portfolio is based on a prototype of the Civil War era. The two artists have expressed similar views of the significance of slavery as an ongoing, unresolved moral problem in American history. Ligon’s paintings often consist of layers of dense coal dust used to write out texts the artist has selected from black authors. While the material produces an exquisite, jet black surface, the many-layered application renders the quotations illegible. They become “evidence of things not seen,” the suggestive title of James Baldwin’s book about a string of racial murders in Atlanta in the mid 1980s. With Thelma Golden, Director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, Ligon is credited for coining the term “Post-Black” to refer to recent art by a generation of African-American artists who do not feel constrained by their racial identity to limit their art solely to the topic of race. Yet “Runaways,” a suite of 10 prints, is based upon the typography and imagery of mid-nineteenth-century handbills seeking the capture and return of fugitive slaves. Each “poster” in the series bears an iconic, stenciled image purported to be the artist himself. The image is accompanied by a verbal description supplied by one of Ligon’s close acquaintances.

Adrian Piper, a Harvard-trained philosopher and first-generation conceptual artist, came to prominence in the 1970s with works that advanced race and “identity politics” into the aesthetic realm. Her work on view, “Everything #18,” like Ligon’s, is also text-based. Upon commercially printed wallpaper that bears a documented copy of the American Constitution Piper superimposes the phrase “everything will be taken away.” The quotation is adapted from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago: “Once you have taken everything away from a man, he is no longer in your power. He is free.” Undeniably confrontational, the work is installed on an imposing free-standing wall in the gallery. By juxtaposing the ominous phrase of the Russian novelist with the founding Enlightenment principles of our democracy—and the modern type upon elaborately hand-written eighteenth-century penmanship—Piper creates a situation in which these contrasting assertions comment on each other.

Robert Gober also confronts us through the medium of commercially printed wallpaper. His “Hanging Man/Sleeping Man” is a fragment of a much larger installation in which the walls of a gallery space were papered with a relentlessly repetitive pattern featuring a black man hanging from a tree alternating with a white man, his head on a pillow, asleep. Like Piper’s work, which in its scale and placement within the gallery space is literally in the viewer’s face, the dissonant content of Gober’s work assaults the viewer. At the same time, the deployment of wallpaper itself is subversive. A papered wall, after all, is a surface where—if one looks at all—one would expect to find an innocuous, purely decorative design.

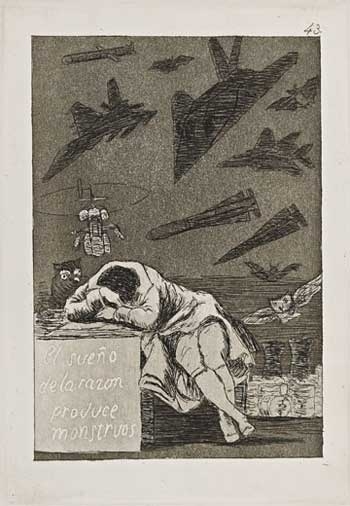

In contrast to Piper and Gober, works by Enrique Chagoya and William Kentridge employ traditional modes of printmaking—etching, aquatint, engraving, and drypoint. These suites demand and reward close scrutiny. In his “Return to Goya’s Caprichos,” Chagoya purposefully updates Francisco Goya’s bitingly satirical series of prints depicting human depravity and folly during the Napoleonic era. In “L’Inesorabile Avanzata [The Inexorable Advance],” internationally acclaimed South African artist William Kentridge revisits newspaper accounts of Benito Mussolini’s mid-1930s invasion and seizure of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). An act of aggression supported by Hitler, this foray, described by some historians as a “last gasp of colonialism,” demonstrated the weakness of the League of Nations and preceded Germany’s march into the Sudetenland and the onset of World War II.

Enrique Chagoya, Return to Goya’s Caprichos, 1999, 8 prints: etching, aquatint, and drypoint, 14 1/2 x 11 inches each. Ed. 35/40. Collection of the Middlebury College Museum of Art. Purchase with funds provided by the Foster Family Art Acquisition Fund

Three additional prints by Kentridge, on loan from a private collection, refer to Albrecht Dürer’s famous—and literally fantastic—woodcut image of a rhinoceros. The beast appears often in Kentridge’s recent art, where it refers to a colorful anecdote about Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the limits of empirical knowledge. Yet it also references a horrific animal slaughter early in the twentieth century, thereby prefiguring the decimation of innocent populations to follow.

Ellen Gallagher’s “DeLuxe,” a massive project of 60 collaged prints, is based on the artist’s personal collection of ads from magazines like Ebony, Our World, and Sepia, from the mid-twentieth century. Targeting the African American public, these monthlies featured advertising for hair products and cosmetics intended to address the imagined needs of their specific readership. Gallagher has revised and updated 60 of these advertisements, adorning the originals with gaudy accretions of plastic and outrageous pop color. In addition to creating a suggestive interplay of barbed racial references, her suite of prints is a tour de force of contemporary printmaking.

Both the Ligon and the Gallagher suites are on loan to the museum from the print collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Piper work comes from a private Chicago collection. Along with the Walker portfolio, the suites by Kentridge and Chagoya and the Gober work are all recent additions to the museum’s growing collection of contemporary art.

The exhibition opens Fri., Feb. 13 at 4:30 p.m. with a gallery talk by Dr. Emmie Donadio, Chief Curator and organizer of the exhibition. Several additional public lectures have been scheduled in conjunction with the exhibition. On Tues., Feb. 17 alumna Kymberly Pinder, Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a celebrated authority on African-American art, will present a lecture titled “Black Man’s Burden: Representing History in Contemporary African American Art.” On Thurs., Apr. 2 President Emeritus and Professor of History John M. McCardell Jr. will speak on “The Civil War and Historical Memory—or Memories.” Both events are free and open to the public. The exhibition will remain on view through Sun., Apr. 19.

The Middlebury College Museum of Art, located in the Mahaney Center for the Arts on Route 30 on the southern edge of campus, is free and open to the public Tues. through Fri. from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sat. and Sun. from noon to 5 p.m. It is closed Mondays. The Museum is accessible to people with varying disabilities. Parking is available in the Center for the Arts parking lot. For further information, please call (802) 443–5007 or TTY (802) 443–3155, or visit the Museum’s website at museum.middlebury.edu.