Groundbreaking Art Deco Exhibit Kicks Off Spring

Deco Japan: Shaping Art and Culture, 1920–1945

January 29–April 24, 2016

For immediate release: 11/16/15

For further information contact: Sarah Laursen, Youngman Curator of Asian Art, at slaursen@middlebury.edu or (802) 443-5491

Middlebury, VT— This January the Middlebury College Museum of Art will host the first exhibition held outside Tokyo dedicated to Japanese Art Deco. Deco Japan: Shaping Art and Culture, 1920–1945 not only provides dramatic examples of the spectacular craftsmanship and sophisticated design long associated with Japan, it conveys the complex social and cultural tensions in Japan during the Taishô and early Shôwa epochs (1912–1945). In these pre-war and war eras, artists and patrons created a Japanese modernism that signaled simultaneously the nation’s unique history and its cosmopolitanism. The vitality of the era is further expressed through the theme of the modern girl, known in Japan as the modan gaaru or moga, for short—the emblem of contemporary urban chic that flowered along with the Art Deco style in the 1920s and 1930s.

The exhibition, which is organized and circulated by Art Services International, includes nearly 200 works drawn from the Levenson Collection, the world’s premier private collection of Japanese art in the Deco and Moderne style as well as 20th-century examples of metalwork in traditional styles. These pieces include sculpture, ceramics, lacquer, glass, wood furniture, jewelry, textiles, graphic design on paper, painting, and woodblock prints; they range from fine art objects made to impress the public at national art exhibitions to goods mass produced for the modern home. The exhibition combines a dynamic range of compelling objects with fresh scholarly perspective to pull viewers into this rich period in world history and visual culture.

Historical Overview

In Japan as in Europe, the Art Deco era—roughly from World War I through World War II—constituted an era of dramatic social and technological change combined with political and cultural turmoil. Japanese society was whipsawed between globalist values that championed western liberalism and isolationist ideologies that sought a restoration of Asian traditions. From the early 1930s Japan’s military invasion of Asia gained pace, culminating in total war with America and Britain from 1941–1945. The Deco era was marked by growing totalitarianism but also by giddy fantasies of luxury and internationalism fed by the burgeoning advertising and film industries. Added to this mix was the reappraisal of craft in terms of fine art, and the explosion of photography and graphic design. Art schools produced designers, and consumer culture provided mass-produced goods to sell to a rising middle class as well as one-of-a-kind objects for those who became wealthy in the war industries. The compelling contradictions of the age are best seen in the Art Deco style, where a facade of elegance parallels a totalitarian gravity, and the theme of national supremacy coexists with that of the alluring café waitress.

The Exhibition

In contrast to previous exhibits and books on Art Deco that organize the material by medium, this exhibition is conceived in a more complex fashion to highlight the cultural, formal, and social aspects of Japanese Deco. The exhibition is divided into five sections, each segueing into the next so that the exhibit unfolds sequentially, providing variety while underscoring key ideas.

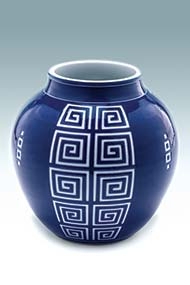

I. Cultural Appropriations

One of the most salient features of Art Deco is eclecticism, referencing cultures ancient and contemporary, familiar and exotic. The exhibition’s opening section explores cultural diversity through five subdivisions. First is the evocation of Euro-American modernity through references to the great cultural capitals of Paris, New York, and Hollywood, represented by fountains, skyscrapers, and the film industry. The spectacle of modern western culture is further expressed in the theme of competitive sports and the Olympic games. In contrast is the historic classicism of pharaonic Egypt, reflecting the Tut craze of early Deco. In an Asian parallel to the “Nile style,” the great 1920s tomb discoveries of ancient China were transformed into Shang dynasty-inspired designs in ceramics and bronzes. Japan’s own classical past is referenced in objects that adapt familiar bird and animal motifs. The literary and artistic animals of the “classical Japan” section lead into a display of exotic zoo animals that underlines the eclectic, cosmopolitan aspect of Deco in general and Japanese Deco in particular.

II. Formal Manipulations

Moving from subject to style, the exhibit next explores the formal qualities of Japanese Deco, demonstrating the broad range of styles associated with Deco as well as the Japanese translation of western idioms. The fundamental Deco preference for simplified geometric shapes, minimal ornamentation, and fresh colors is witnessed in abstract works in a range of materials. They also attest to the Japanese desire to reinterpret a variety of crafts. The Deco adaptations of earlier styles—including Art Nouveau and Cubism—and familiar themes is most evident in the sections on natural motifs, which includes works featuring plants, animals, birds, and auspicious creatures.

III. Over and Under the Sea

While the other sections of the exhibition examine cultural connections, styles, or social themes, this segment integrates all of the categories to demonstrate how objects may operate on multiple levels. It also highlights the Deco era themes of travel, speed, consumption, luxury, exoticism, and elegant distortion of form. This section presents the paradigmatic Deco realms of the ocean liner and beach resort, the distinctly Deco subject of tropical fish and shells, and the ubiquitous Deco motif of the Flying Fish—the ultimate 1930s emblem of stylish power in sea and air.

IV. Social Expressions

One of the most fascinating aspects of Japanese Deco is the ways in which the style was linked with social and political themes ranging from militant nationalism to social and personal liberation. The war-era context of some Deco objects is evident in a lacquer box, made for a public exhibit in 1943, that depicts a heron snatching a fish in its beak—symbolizing the hope for victory in the era of the “decisive battles.” The phoenix and the dragon signify related themes of imperial prestige. The sunburst motif was common in European Deco as a symbol of progress, while in Japan it was linked to the rising sun emblem of imperial power and military expansion.

In sharp distinction to these masculine and historically sanctioned ideals is the dominant Deco-era theme of the “modern girl,” Japan’s jazz age icon of contemporary style, pleasure, and consumption. In many ways an evolution of the stylized courtesan who epitomized the ukiyo or “floating world” of the Edo period, the moga was carefully constructed via cosmetics and hair ornaments. Equally important was her transgressive behavior, symbolized by smoking and drinking, which encouraged elegant Deco-style cocktail glasses and smoking sets. The modern girl’s milieu was the café and dancehall, where active movement of dance bespoke social and personal freedom. The ultimate example of this hedonistic culture is the nude, perhaps best represented by the cover design for the sheet music of “The Miss Nippon Song.”

V. The Cultured Home

The exhibition concludes by bringing Art Deco home, literally. The Deco style was not only associated with public spaces, whether dedicated to the nation or to entertainment, but was also linked with luxury commodities that decorated the modern “culture house,” preeminent symbol of the “culture lifestyle.” Deco-style objects made for domestic use consist of furniture and such furnishings as rugs, lamps, clocks, and bowls. They also include human and animal figurines, demonstrating both the ubiquity of the Deco style and the spread of customs like keeping pure bred dogs and cats.

The Collection

The Levenson Collection, the world’s premier private collection of Japanese art in the Deco and Modern style from which Deco Japan is assembled, brings together an unprecedented group of two- and three-dimensional Japanese objects made during the Deco era. It offers an unparalleled group of works in metal, including those by leading artists like Tsuda Shinobu (1875–1946). It is also strong in lacquer, ceramics and cloisonné, featuring objects by Imperial Court Artists and winners at the annual Education Ministry Art Exhibition. It contains representative examples of work in wood, glass, and textiles. The Levenson Collection provides a striking and fascinating mix of objects that exemplify the height of the Deco style and express relevant social themes of nationalism, personal liberation, and consumer culture. However, what makes the collection particularly dramatic as an exhibition is its secondary focus on the theme of the modern girl. The range of these works—from monumental paintings to woodblock prints, sheet music, and postcards—provides great visual diversity and balances the industrial arts.

Scholarship

The exhibition is curated by Dr. Kendall H. Brown, Professor of Japanese Art History at California State University, Long Beach. Dr. Brown has developed exhibitions of 20th-century Japanese art for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and, for the Honolulu Academy of Art, he organized the exhibition, Taisho Chic: Japanese Modernity, Nostalgia and Deco.

Accompanying the exhibition is a full-color catalogue, illustrating all of the objects in the exhibition and featuring essays that explicate the major themes and discuss the individual works. Also included are essays by Dr. Brown and by specialists from Europe, America, Australia, and Japan.

The exhibition is drawn from The Levenson Collection and is organized and circulated by Art Services International, Alexandria, Virginia. Support has been provided by The Chisholm Foundation and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation. His Excellency, Mr. Ichiro Fujisaki, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Japan to the United States of America, is Honorary Patron of the exhibition. At Middlebury it is supported by the Christian A. Johnson Memorial Fund and the Friends of the Art Museum.

The Middlebury College Museum of Art, located in the Mahaney Center for the Arts on Rte. 30 on the southern edge of campus, is free and open to the public Tues. through Fri. from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sat. and Sun. from noon to 5 p.m. It is closed Mondays. The museum is physically accessible. Parking is available in the Mahaney Center for the Arts parking lot. For further information and to confirm dates and times of scheduled events, please call (802) 443–5007 or TTY (802) 443–3155, or visit the museum’s website at museum.middlebury.edu.