Matthew Harris Jouett's Portrait of George Washington

The following essay was originally printed in the Middlebury College Museum of Art Annual Report for 2002–2003.

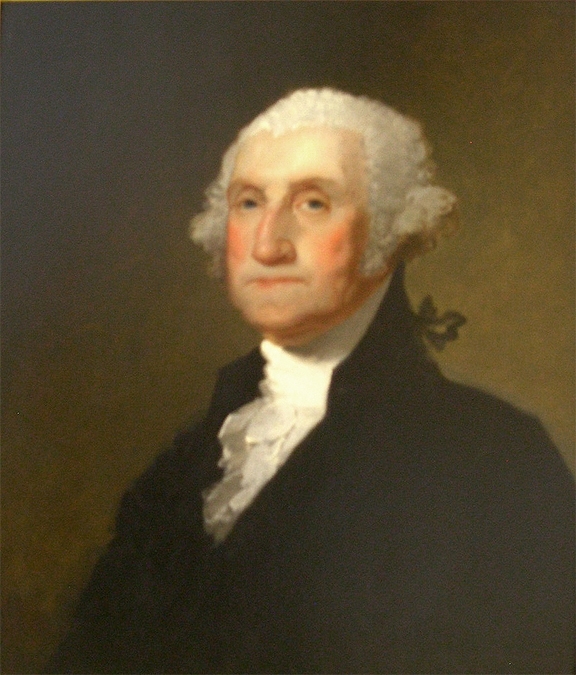

The Middlebury College Portrait of George Washington, Reattributed

In 1796 Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) painted a pair of portraits of George and Martha Washington, from life, on commission from Mrs. Washington. Stuart was very pleased with the results and, recognizing that the portrait of Washington in particular would be popular with the public as well, left them unfinished and never delivered either canvas to the Washingtons. In 1831 the pair was purchased from Mrs. Stuart by the Boston Athenaeum, and they have come to be known as the “Athenaeum” portraits. In 1980 they were acquired jointly by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.[1] Stuart painted many replicas of George’s portrait (he never copied Martha’s) and charged one hundred dollars apiece for them.[2] According to the artist’s daughter Jane:

[3]

None of these replicas is signed and only a few are fully documented. In addition, many artists, both during Stuart’s lifetime and after, copied this likeness, furthering its dissemination as the best-known image of the first president. It can therefore be difficult to separate Stuart’s more hastily executed replicas from the copies painted by his most competent followers.

In 1966 the Middlebury College Museum of Art received an “Athenaeum”-type portrait of George Washington as a bequest from Muriel Selden (fig. 1). Known as the “Sanders-Dallam-Peter Portrait,” it came well documented with a provenance going back to Lewis Sanders, a prominent early nineteenth-century Kentuckian. The earliest published reference to the painting is in George C. Mason’s The Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart, in which is quoted a letter to Jane Stuart from a Miss Johanna Peter, whose mother then owned it:

[4]

She gave a very similar account in a notarized statement of February 27, 1915.[5] The portrait was included, as by Stuart, in Mason’s and Park’s respective lists of the artist’s work, and in John Hill Morgan and Mantle Fielding’s checklist of the portraits of Washington.[6] The attribution has not been questioned, until now.

Johanna Peter in her two accounts mentions a companion portrait of Thomas Jefferson, which was sold in 1874 by William Smith Dallam’s daughter Letitia Preston Dallam Root (Miss Peter’s aunt) to the United States government and which hangs in the White House. This portrait (fig. 2), like the one of Washington, is recorded in both Mason and Park as by Stuart,[7] but in 1943 it was reattributed to Matthew Harris Jouett.[8]

Jouett (1788–1827) was born in Kentucky and resided there most of his life; his father was Captain Jack Jouett, a friend of Thomas Jefferson. The younger Jouett worked as a portrait painter in his native state before the War of 1812, in which he served as a captain of militia, but at the war’s end decided he needed further training. In 1816 he traveled to Boston, where he studied for four months with Gilbert Stuart. Stuart took a great liking to the young artist, whom he called “Kentucky,” and taught him much about painting. Jouett kept a detailed journal during his time in Boston, which is one of the most important sources of information about Stuart’s methods of painting. He then returned to Kentucky, set up his studio in Lexington, and worked there and elsewhere in the South as a portraitist until his death ten years later at the age of thirty-nine.[9]

As John Hill Morgan remarked in his study of Stuart’s pupils, “With the possible exception of [James] Frothingham, no pupil absorbed more from Stuart than did Jouett, and the pity of it is that he was so circumstanced that full training at home or abroad was denied him.” Imitating Stuart’s style (Jouett even laid out his palette like Stuart’s) could not make up for his lack of skill in drawing and understanding of human anatomy, and, although he was the best painter then working in Kentucky, he never rose to the top rank of American artists. Nevertheless, his portraits generally are satisfactory in execution and show the influence not only of Stuart but also of Thomas Sully, whom Jouett knew and admired as well.[10]

The portraits of Washington and Jefferson, regarded by William Smith Dallam and his descendants (and presumably by Lewis Sanders, too) as companion pieces, evidently are by the same hand. They are Stuartesque in appearance but weaker in execution when compared with Stuart’s originals.[11] However, although the execution is weaker, it is not careless; the Washington in particular is very carefully rendered. By contrast, a replica by Stuart himself (fig. 3), is quickly and summarily painted, but is also a stronger, better-modeled likeness due to Stuart’s thorough understanding of anatomical structure and sure grasp of technique. Although Jouett is believed to have painted several copies of the “Athenaeum” portrait, only one other has been located to date (fig. 4). It is competently executed but is not as faithful a copy as the one belonging to the Middlebury College Museum of Art.[12] It may plausibly be suggested, therefore, that the portrait owned by Middlebury was painted by Jouett directly from the original “Athenaeum” portrait while he was a pupil of Stuart. Although the master’s hand is not evident, the painting would have been painted under his close supervision.

A de-attribution from Gilbert Stuart to a lesser painter is perhaps a not altogether happy circumstance, even if scholarship is best served by an attribution that is correct rather than optimistic. Yet Matthew Harris Jouett, if not an artist of the first rank, was one whose abilities and talent were respected by such fine artists as Stuart, Sully, and George Peter Alexander Healy; and his portrait of George Washington, if not quite up to his master’s level, is still of such quality as to have misled the leading authorities on Stuart. Jouett is believed to have painted more than three hundred portraits and the bulk of his work is still to be found in his native Kentucky. The Middlebury College Museum of Art is the only public institution in Vermont to possess a work by this “old master of the bluegrass.”

David Meschutt, formerly Curator of Art at the West Point Museum, United States Military Academy, is a Ph.D. candidate in Art History at the University of Delaware. He also has worked for the Frick Art Reference Library and the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation. He has published a number of articles on American and British portraiture in such publications as The American Art Journal, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, and The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts and has curated exhibitions on the sculptor John Henri Isaac Browere for the New York State Historical Association and on the artist Alonzo Chappel for the Brandywine River Museum.

Notes

[1] The best account of Stuart is Dorinda Evans, The Genius of Gilbert Stuart (Princeton, 1999). Excellent discussions of Stuart’s portraits of Washington can be found in Ellen G. Miles, George and Martha Washington: Portraits from the Presidential Years (Washington, D.C., 1999), pp. 38–47, and in her article “Gilbert Stuart’s Portraits of George Washington,” in Marc Pachter et al., George Washington: A National Treasure (Washington, D.C., 2002), pp. 77–101. Lawrence Park, Gilbert Stuart (New York, 1926) is now very dated but remains the only catalogue raisonné of Stuart’s work. An incomplete list of Stuart’s work may be found in George C. Mason, The Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart (New York, 1879).

[2] In a letter of April 20, 1796, to a Mr. P. Van Gaasbeek, John Vanderlyn (1775–1852), then an assistant to Stuart, wrote that “Mr. S. has 100. Doll[ar]s for a Portrait of the President which is his price for painting a likeness here[?] now.” John Vanderlyn Papers, Senate House State Historic Site, Kingston, New York, quoted in Miles 2002, p. 94. It is not known exactly how many replicas Stuart painted. Park listed 77, but a number of these are now known to be by other hands, and Park did not record several replicas that certainly are by Stuart.

[3] Jane Stuart, “The Stuart Portraits of Washington,” Scribner’s Monthly 12 (1876), p. 369.

[4] Mason 1879, p. 109. Jane Stuart is not identified as the recipient of Miss Peter’s letter, but she is so identified in a privately printed report on the painting prepared by the dealer Jonce McGurk when he offered it for sale in 1917. A copy of the report is in the Special Collections Department, Starr Library, Middlebury College.

[5] Original document in the possession of Middlebury College (photocopy kindly furnished to me by Dr. Richard Saunders, Director, Middlebury College Museum of Art). In her notarized statement, Miss Peter includes the comment, “Matthew H. Jouett the artist, a pupil of Stuart, frequented Dallam’s house, painted many portraits in the family, and … would have known had the picture not been genuine.” The wording of her statement implies that Jouett was never actually called on to authenticate the picture and, when compared with her comments published nearly forty years before, reads as an afterthought. (She made no mention of Jouett in her letter to Jane Stuart published by Mason.) As she could not have known Jouett, who died almost ninety years before she made her notarized statement, her opinion as to what he may or may not have said about the Washington portrait cannot be taken as serious evidence to support an attribution to Stuart. Clearly, however, the tradition in the Dallam family was that Stuart painted both it and the Jefferson portrait that belonged to Miss Peter’s aunt Letitia Preston Dallam (Mrs. William N. Root).

[6] Mason 1879, p. 109; Park 1926, p. 888, no. 93; John Hill Morgan and Mantle Fielding, The Life Portraits of Washington and Their Replicas (Philadelphia, 1931), p. 306, no. 96. Morgan did not have the opportunity to examine the portrait, although it was seen by Fielding. It belonged at that time to Albert H. Wiggin of New York City, who had purchased it from Miss Peter and her siblings (through the New York dealer Jonce McGurk) in 1917. It subsequently belonged to Lynde Selden, whose widow bequeathed it to Middlebury College.

[7] Mason 1879, p. 208; Park 1926, p. 443, no. 447. Mason reported that the portrait “is not thought equal to other portraits from the same pencil.”

[8] Fiske Kimball, “The Stuart Portraits of Jefferson,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 23 (June 1943): 342–43. Kimball’s attribution of the portrait to Jouett was supported by the art historian William Sawitzky (verbally, at the Frick Art Reference Library, July 12, 1944) and has been accepted by all authorities on Stuart, Jouett, and Jefferson, as well as by the White House Curator’s office.

[9] The most recent detailed study of Jouett’s life and career is William Barrow Floyd, Matthew Harris Jouett: Portrait Artist of the Antebellum South (Louisville, 1980). Floyd also discussed Jouett in his Jouett-Bush-Frazer: Early Kentucky Artists (Lexington, Ky. 1968). Earlier accounts of Jouett are Samuel Woodson Price, The Old Masters of the Bluegrass (Louisville, 1902), and E. A. Jonas, Matthew Harris Jouett: Kentucky Portrait Painter (Louisville, 1938).

[10] John Hill Morgan, Gilbert Stuart and His Pupils (New York, 1939), p. 58. Edna Talbott Whitley, Kentucky Ante-Bellum Portraiture (Richmond, 1956), p. 704, is the source for the information about Jouett setting his palette in imitation of Stuart’s. Jouett also named his second son after Stuart; Floyd, p. 13.

[11] For a detailed discussion of Stuart’s portraits of Jefferson, see David Meschutt, “Gilbert Stuart’s Portraits of Thomas Jefferson,” The American Art Journal 13, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 2–16. Stuart, of course, did not conceive his originals of Washington and Jefferson as a pair.

[12] It belongs to the George Washington’s Fredericksburg Foundation (formerly the Kenmore Association), Fredericksburg, Virginia, which received it as a gift from Mrs. Virginia Lovell Hodge. Mrs. Hodge in turn acquired the portrait around 1904 from a member of the Innes family of Kentucky. Mrs. William H. Martin, in her checklist of Jouett’s work, Catalogue of Paintings by Matthew Harris Jouett (Louisville, 1939), p. 51, lists three Washington portraits: the one at Kenmore; one then owned by Mrs. James Ross Todd (about which nothing more has been discovered but which presumably was another copy of the “Athenaeum” type); and a copy of Stuart’s earlier “Vaughan”-type portrait. This last is a well-executed painting, “but definitely not by Matthew Harris Jouett,” according to John Hill Morgan (in an undated verbal opinion recorded by the Frick Art Reference Library).

Mention should also be made of a portrait, attributed to Stuart, of Lewis Sanders, the first owner of Middlebury’s painting and of the Jouett portrait of Jefferson in the White House. It is not recorded in either Mason or Park, but a photograph is on file at the Frick Art Reference Library in New York. In 1939 it belonged to a descendant, Mrs. Rodolphe L. Agassiz of Pride’s Crossing, Massachusetts, but is at present unlocated. It is in oil on panel and measures 26 by 21 1/2 inches. In photograph the Stuart attribution seems plausible, but on the back is a sketch of an unidentified man, clearly not Sanders, that looks very much like Jouett’s work. As plausible as an attribution to Stuart seems in photograph, an attribution to Jouett is equally likely, for the Sanders portrait compares well stylistically with one of his most Stuart-like paintings, the portrait of Justice John McKinley (c. 1817–18; United States Supreme Court, Washington, D.C.). Firm reattribution of the Sanders portrait to Jouett must wait, however, until the painting itself is again available for examination.