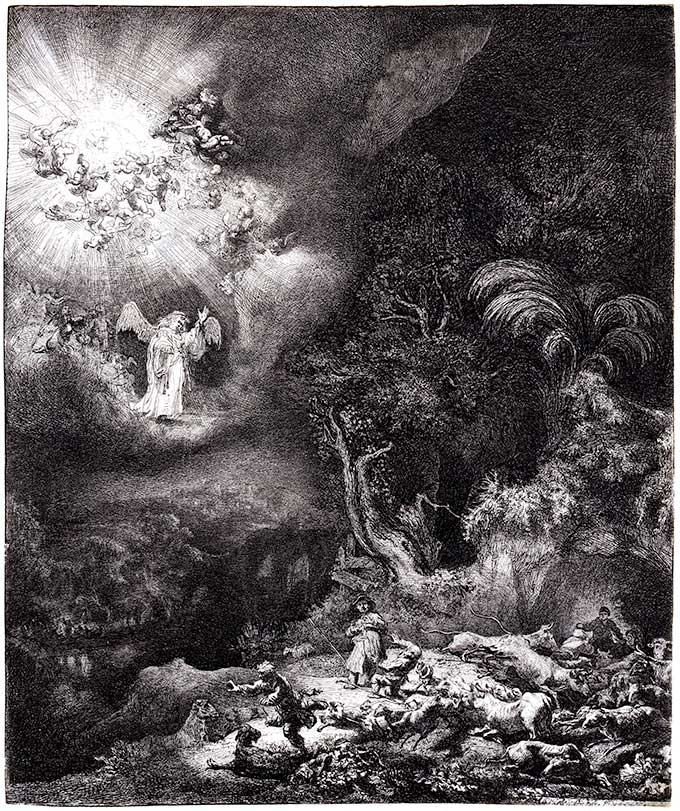

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds

Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669), The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, 1634, etching, drypoint, and engraving on paper, 10 3/8 x 8 5/8 inches. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art, purchase with funds provided by the Walter Cerf Art Fund, the Fine Arts Acquisition Fund, and the Memorial Art Fund, 2002.012

In 1634 Rembrandt was busy filling commissions as Amsterdam’s most sought-after portraitist. He was also painting religious works that pushed the dramatic stylistic devices of Baroque artists like Caravaggio and Rubens to their theatrical limits. In this print, as in those paintings, the artist presents small figures in a vast, dark setting; he uses gesture to convey drama and spotlighting to focus the viewer’s attention upon it. Consistent with Rembrandt’s contemporary painting, as well, is a high degree of finish, which drew the praise of his contemporaries for its attention to detail, variety of poses, and accuracy of emotion.

In pursuit of such realism Rembrandt included northern European cows and dogs along with Biblical sheep. He studied popular figures like rustics and beggars, evident here in the characterization of the shepherds who tend their flocks or warm themselves in a cave against the winter night. To explore emotions, Rembrandt used his own self portraits, sometimes shading his eyes with a cap to make his viewer focus on a single part of the face as a communicator of psychology. This device appears in the artist’s treatment of the central shepherd, whose face is framed by the black brim of his hat.

The figures are set in a deep diagonal nocturnal landscape with a river, a bridge, and a castle on a hill illuminated by moonlight. Above them, though, the heavens break open with a burst of heavenly light that exposes the forms of the dove of the Holy Spirit and attendant putti and also picks out the gesture of the Angel of the Annunciation as he addresses the tiny figures below. “Be not afraid” takes on new meaning in the midst of the pandemonium, as the blast of light scatters shepherds and flocks. One shepherd flees and another falls back with arms raised. This one’s hatted companion reacts to his friend’s astonishment in a scene that exemplifies the artist’s supreme gift for expressing the essential dramatic point of his narratives.

Beyond providing a record of Rembrandt’s style as a painter at this point in his career, this print is also important as an example of the artist’s development as a printmaker. It is considered a masterpiece of his early style in its own right and a watershed work in his evolution as an etcher. Etching, a relatively new medium in his day, was generally still used by artists in the illustrative fashion of engravings—with rigidly disciplined mark making. In contrast, Rembrandt grasped its potentials for capturing something of the spontaneity and colorism of drawing. He often improvised and reworked images directly on his plate, as in this case, using a soft ground to enhance the freedom of his marks. His contemporaries considered the resulting scrawls and scribbles and irregular strokes without outline a bit bizarre, but through them Rembrandt was able to create dark tonal areas of great vigor. Thus the landscape around the shepherds has been developed with a fine mesh of cross-hatching and multiple bitings to produce areas of varying shadow rather than outlines. The effect foreshadows mezzotint in pushing the limits of etching to approach the qualities of grisaille (painting in black and white only). More than a mere emulation of painted imagery, however, this most pictorial of Rembrandt’s prints utilizes broken line work (as in the apparition in the sky) and a rich layering of black on black that explores the particular capabilities and qualities of the etching medium. In such ways “Angel Appearing to the Shepherds” marks a significant step in the artist’s establishment of etching as a technique for artistic creation in its own right.

Glenn Andres

Professor, History of Art and Architecture