Rokeghem Hours (Use of Rome), by the Masters of Raphael de Mercatellis

Rokeghem Hours (Use of Rome), Belgian, Bruges, c. 1500, in Latin and Dutch, bound illuminated manuscript on parchment, 2 large and 16 small miniatures by the Masters of Raphael de Mercatellis, 7 x 5 1/2 x 2 1/16 inches closed. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art, purchase with funds provided by the Reva B. Seybolt ’72 Art Acquisition Fund and the Friends of the Art Museum, 2012.005

This recent acquisition, a richly illuminated late 15th–early 16th century manuscript called the Rokeghem Hours, is named for the family for whom is was originally made, the van Rokeghem, who owned lands outside of Bruges, in present-day Belgium. It was created for one of the members of that family—likely for one of the women—by a group of Bruges illuminators called the “Masters of Raphael de Mercatellis.”

Saint John the Baptist and Saint Anthony Abbot (both from the Suffrages of the Saints)

Books of Hours are prayer books that contain at their heart a series of devotional prayers called either the Little Office of the Virgin or the Hours of the Virgin, devotional prayers to the Virgin Mary that Christians uttered throughout the course of the day. The Hours were often augmented with other types of devotional texts such as the Penitential Psalms, the Suffrages of the Saints, and the Office of the Dead, all of which our book includes. These manuscripts, quotidian objects used by nobles and non-nobles alike, were rich and important parts of medieval visual and material culture. Made for private devotion, they allowed one to take in fully the word, which was itself venerated as a sacred object.

There is evidence that the Rokeghem Hours represents the work of two women from the Carmelite convent of Sion in Bruges, the illuminator a woman named Cornelia van Wulfschkercke and the scribe a woman named Margarita Bruynruwe. This makes our text a relative rarity from a time when many people purchased Books of Hours and other texts from commercial workshops, typically run by men.

One of those men, Raphael de Mercatellis, was a wealthy bibliophile abbot of the church of Saint Bavo in Ghent, which, then as now, also housed Jan and Hubert van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece. The abbot owned at least one other manuscript containing illuminations by van Wulfschkercke and Bruynruwe that shares much in common with our Book of Hours. This connection to the Church of Saint Bavo is particularly important, because the illuminations in our book show clear and exciting connections to Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling, among other painters.

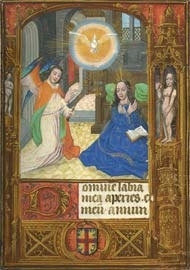

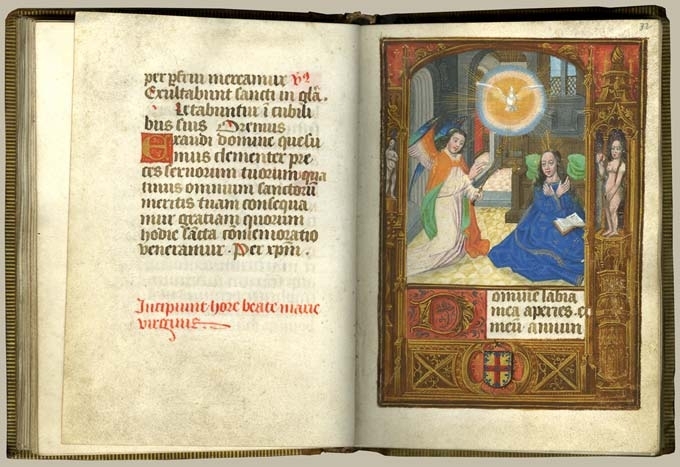

The Annunciation (beginning of the Office of the Virgin)

One of the more striking full-page illuminations in this book, shown above, is a traditional scene of the Annunciation to Mary with elaborate architectural margins. Small figures of Adam and Eve stand in tiny niches flanking the Annunciation scene, their presence denoting their significance as both the first parents and also the first sinners. Eve’s larger figure is placed at the same level as Mary’s, denoting Mary’s significance as the “New Eve” and the vessel through which human salvation, in the form of Christ, will be brought into the world and thus reverse the sins of Adam and Eve. This combination of scenes is derived in large part from the Ghent Altarpiece, with the poses and placement of our Adam and Eve directly inspired by van Eyck’s nearly life-sized figures. Likewise, the Annunciation scene—particularly Mary’s pose, with her arms folded across her chest—is derived from Mary’s pose on the exterior of the Ghent Altarpiece, as well as from other models.

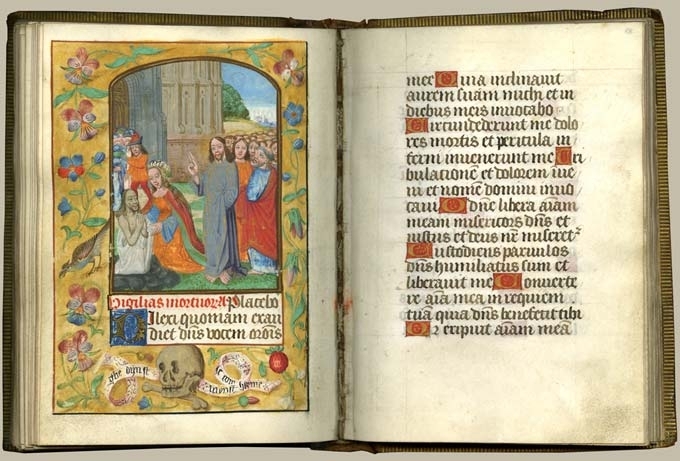

The Raising of Lazarus (beginning of the Office of the Dead)

Between the thirteenth and the sixteenth centuries more of these texts were bought and sold, bequeathed and inherited, printed and reprinted than any other text, including the Bible. Such objects are thus a critical part of understanding the material and visual culture of the later middle ages and the early modern period. Since so many of these books were created for secular women, they are crucial parts of the history of women in the west. Arguably, they are a complex and not entirely straightforward part of the story—or even the pre-history—of women’s emancipation.

Eliza Garrison

Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture