Pastoral Vermont: The Paintings and Etchings of Luigi Lucioni

–

There is perhaps no artist whose work provides a more crystalline twentieth-century expression of the bucolic and highly romanticized Vermont landscape than that of Luigi Lucioni. He understood better than most that the inspiration he drew from the pristine natural beauty of the Green Mountain State paralleled the harmonic balance of humanity and nature that many Americans sought in their own lives. As a result, his verdant panoramic landscapes populated by church spires and rusticated farm buildings appeal—as much today as they did when he first painted them—to our nostalgic wish for a seemingly more simple existence.

Lucioni’s paintings of Laurelton Hall (Oyster Bay, NY), where he stayed as a fellow in the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation’s summer program for young artists, reveal the loose and impressionistic style of his early years. He painted with broad brush strokes and a rich chromatic range, frequently using a palette knife to accentuate surface textures. Though the thick and sometimes harshly applied layers of paint acknowledge the influence of his teachers and other artists, such as Childe Hassam, with whom he had studied, his own sensitivity to light and detail come through, and one begins to get a sense of the artist’s struggle to determine a more personal style.

His 1930 oil on canvas titled Anachronisms (collection of Mr. and Mrs. William H. Turner, Montclair, NJ), arguably the most ambitious and original still life of his entire career, represents the culmination of a series of studio interiors that mirror, in many ways, the work of his contemporary Charles Sheeler. With its tilted vantage points and radical cropping of elements, it is a departure from the more traditional Cézanne-inspired compositions he had previously painted, and it seems that by this point Lucioni had fully allowed himself to adopt a more meticulous method of painting that required many hours of painstaking attention to detail.

Later that same year Lucioni met Electra Havemeyer Webb who was to become his single most important patron. Mrs. Webb commissioned him to paint a Vermont landscape for her daughter’s wedding and invited him to stay at the family’s summer estate in Shelburne. The state’s verdant mountainous terrain had such a profound effect on him that he later exclaimed, “I was reborn in this majestic setting and I fell in love with Vermont.”

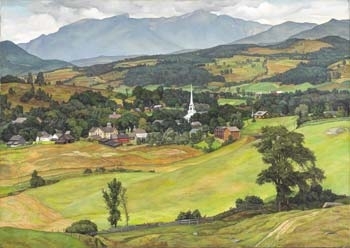

Luigi Lucioni, Village of Stowe or Stowe Valley, Mount Mansfield, 1931, oil on canvas, 24 x 34 inches. Minneapolis Museum of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Gift of Mrs. G. P. Douglas.

In Vermont Lucioni’s painstakingly meticulous style and his sensitivity to the natural world found true inspiration, and art patrons began to take notice. In his archetypal 1931 work Village of Stowe, Vermont (collection of Minneapolis Museum of Art), a work commissioned by a wealthy Minneapolis lawyer, Lucioni paints the village silhouetted against the grand panorama of Mount Mansfield. Using a reductive style steeped in clarity and precision Lucioni reaffirmed the mythical image of Vermont as a pastoral haven from the complexities of modern, twentieth-century life.

Lucioni also recognized the need to produce works that would be affordable for the general public. Following his first successful painting trip to Vermont in 1930 he solidified a regimen to which he would adhere religiously for the remainder of his career. He spent his summers in Vermont, first on the Webb estate and later increasingly in the area around Manchester, where some of his signature subjects became Equinox Mountain, Dorset Hollow, and the Ekwanok Golf Course. Then he returned to New York City for the winter, where he busied himself making etchings after some of his summer landscapes. Thus, over the entire arc of Lucioni’s career there is a virtually seamless relationship between his paintings and his etchings.

Luigi Lucioni, Vermont Landscape, 1932, etching on paper, 7 x 10 inches. Middlebury College Museum of Art. 1970.023.

Sometime in the mid-1930s Lucioni also took a serious interest in the medium of watercolor, perhaps in part because in the depths of the Depression it was a less expensive alternative to oil paints. These paintings provided yet another more affordable option for a wider audience to acquire his works. The results were astonishingly seductive, and over the next two decades he produced virtuoso, large-scale watercolors of enormous dexterity, including his 1956 painting Early Autumn now in the Middlebury collection. The soft yet distinct shadows and subtle variations in hue that Lucioni achieves in this work precisely capture the characteristic shift from the heavy, hazy air of August toward that lighter, crisper atmosphere that signals the coming of fall in Vermont.

Luigi Lucioni, Early Autumn, 1956, watercolor on paper, 14 x 20 inches. Middlebury College Museum of Art.

While landscapes and still lifes provided fulfilling subject matter for Lucioni throughout his career, the same cannot be said of portraits. Although his meticulous style and intense observation of subjects lent itself to portraiture, he lamented that he did not really enjoy it. His most successful portraits date from the first half of his career, such as the 1939 portrait of the blues and jazz vocalist Ethel Waters and the 1942 portrait of the Italian vocalist Mili Monti. However, like many portrait painters he was most comfortable painting friends and family, where he had a genuine emotional attachment for the person depicted, and he received no criticism. Indeed, truer to Lucioni’s personal style is his 1941 portrait of his father. The image is frank and unassuming, yet Lucioni’s sensitivity to light and detail, ever present throughout his career, imbue the sitter with a sense of simplicity and a quiet dignity.

Regarding subject matter, one of the most important of his various Vermont compositions is Vermont Landscape, in which his vision crystallizes in a single, panoramic view where a solitary copse of elms takes center stage. This work signals the emergence of a sustained theme in Lucioni’s career, often considered to be his hallmark—his discerning depiction of trees, particularly birches, and his enormous love for them as individual specimens. In some ways, as the years passed, they took the place of human portraits, which he eventually found uncomfortable to record. But in a tree, whether it was an elm, poplar, pine, locust, maple, or birch, such compositions as Beyond the Pine enabled Lucioni to establish an Emerson-like kinship for the beauty and character of the natural world.

Lucioni continued to paint trees throughout his career, and although in his later years he complained that he had grown tired of painting such compositions, it was not until 1985 that he formally said good-bye to this subject with what can be seen as his last major accomplishment, Farewell to Birches (collection of Southern Vermont Art Center). This painting, looking through a birch grove across the Ekwanok golf course toward the steeple of the Congregational church in Manchester, was a subject he had painted repeatedly for more than forty years. Through his deft sense of composition and his masterful rendering of light and detail, he creates a sense of the unassailable perfection of the moment layered with the easy peace one feels in the company of old friends. It is astonishing that so late in his career he could sustain command of the paintbrush and achieve such remarkable results. It seems almost as though Lucioni was saying to himself that he would depart from the world of painting on his own terms and with the level of craftsmanship he had sustained throughout his career.