The Soviet Century: 100 Years of the Russian Revolution

–

The 1917 Russian Revolution ushered in a new era of human history. The objects featured here showcase four different moments in Russian and Soviet history, demonstrating how material culture served as a space in which governing forces, both Tsarist and Communist, sought—sometimes unsuccessfully—to gain legitimacy and shape the country’s moral fabric.

Imperial aspirations, religious identity, and nationalism intertwined in the Tsarist era. The double-headed eagle (inherited from Byzantium) legitimated the claim of the Romanov dynasty to both secular and sacred authority in an empire that sprawled across Europe and Asia. By the late nineteenth century, this symbol graced objects ranging from royal glassware to items intended for popular consumption.

Orthodox icons, intended to focus the prayers of the faithful, were found in churches, peasant huts, and imperial palaces alike. Personal icons of the wealthy often boasted immaculately carved and bejeweled frames that exemplified the intersection of spiritual and worldly concerns.

Though governing a multi-ethnic and multi-religious empire, the autocracy sought a unifying national identity through romantic idealization of the peasantry. Elaborate and costly decorative pieces like miniature peasant houses and images of folk heroes symbolized an eternalized image of “Russianness.” While bearing slight resemblance to the reality of peasant life (serfdom was only abolished in 1861), this celebration of “Russian” culture accompanied imperial expansion in the Caucasus and Eurasia.

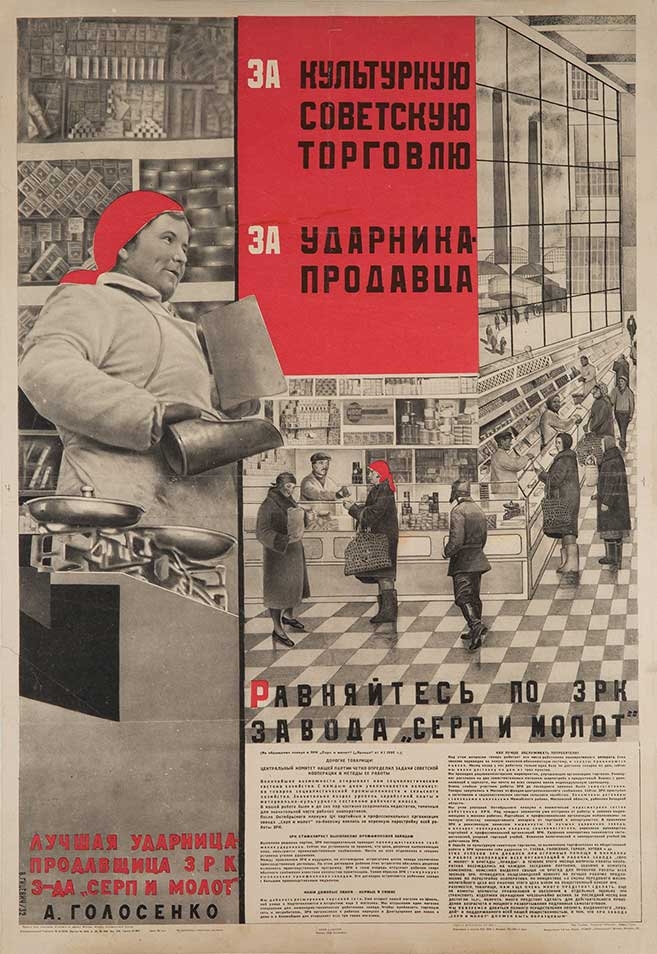

Vera Adamovna Gitsevich (Russian, 1897-1976), Za Kultumuyu Sovetskuyu [To the Cultured Soviet Trade], 1932, two-color lithograph, 34 x 23 3/4 inches. Purchase with funds provided by the Memorial Art Acquisition Fund

The 1917 Revolution ushered in the first self-declared Communist state and required new symbols of legitimacy. For a largely illiterate population, images were particularly potent. Vibrantly colored posters became a favored means of communicating a new value system that contrasted with the elite cultural products of the Romanov dynasty.

The Second World War (or “Great Patriotic War” as it was known in the USSR) provided a new framework for the relationship between individual and state. This military conflict bound together in patriotism a Soviet people still reeling from the terror of dictator Joseph Stalin’s agricultural collectivization and purges. Insightful Soviet artists such as Dmitri Baltermants were nonetheless able to capture the contradiction between the official narrative of triumphant victory and the complexity of lived experience.

If the reality of life in the Soviet Union was challenging for many citizens, the economic desperation after the country’s collapse in 1991 left its own marks upon the population of now-independent Russia. In his work, photographer Alexey Titarenko conveys the uncertainty and flux of 1990s Russia, in which a clear narrative of legitimacy and belonging seems absent. A generation later, as we mark the centennial of the 1917 Revolution, it is timely to reflect on the complex connection between the individual and broader society, not only in Russia but around the world.

Rebecca Simon ’19

Students in Professor Rebecca Mitchell’s Fall 2017 course, Revolutionary Russia (HIST 313), composed the interpretive materials for this installation.