Mao, Sitting Bull, and Others: Recent Gifts from the Andy Warhol Foundation

–

The Andy Warhol Foundation has recently made a gift of ten prints to the museum. The ten trace the evolution of Warhol’s career from his breakthrough 1962 Campbell’s Soup Can series to the Cowboys and Indians portfolio he produced in 1986, shortly before his untimely death. With this gift the museum has doubled the number of Warhol prints in its growing collection.

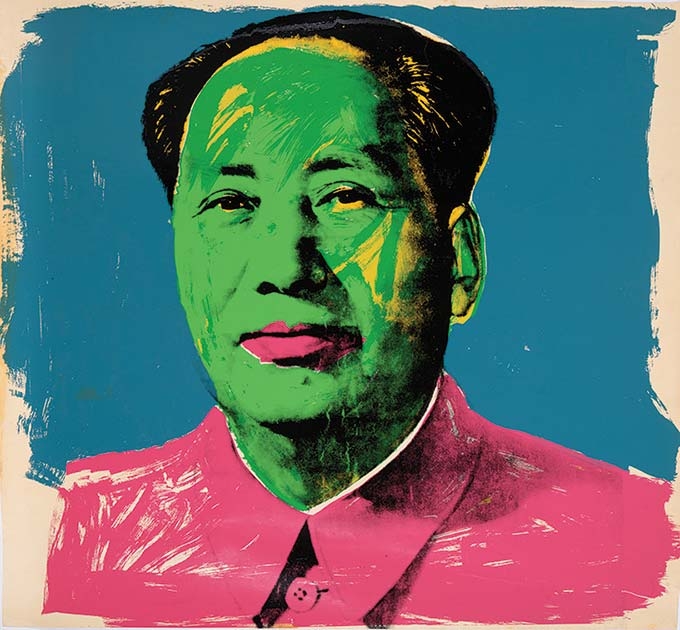

Illustrating the diversity of Warhol’s sources of inspiration, the prints range from the deeply personal (an image of the pet pig that “Baby Jane” Holzer, one of his superstars, gave to him) to a garish portrait of Mao Zedong, one of the most widely reproduced of Warhol’s iconic images. The portrait of Goethe in the exhibit reflects the artist’s familiarity with well-known art historical sources, while an image of Sitting Bull is evidence of his fascination with native American lore. A portrait of Queen Ntombi of Swaziland comes from four images of Reigning Queens. The largest portfolio in Warhol’s works, Reigning Queens contained sixteen images of the four ruling female monarchs in the world in 1985: Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, and Ntombi.

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972, screenprint on paper, 36 ¾ x 39 ¼ inches. Extra, out of the edition. Designated for research and educational purposes only. Collection of Middlebury College Museum of Art. Gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2014.027. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Although Warhol is widely considered the embodiment of the American Pop Art movement, two internationally commissioned prints in this exhibition are proof that his fame extended far beyond American shores and subjects: Ingrid Bergman (the Nun), a portrait of the actress in her legendary 1945 role in film The Bells of St. Mary, was a Swedish commission; and Die Welt, the German daily, commissioned Fiesta Pig.

Often regarded as the most influential artist of the second half of the twentieth century, Warhol challenged the introspective, subjective style of Abstract Expressionism that dominated post-war American art of the 1940s and ’50s. His elevation of such quotidian objects as Campbell’s soup cans and Brillo soap boxes to the status of subjects fitting for fine art undermined the profundity and seriousness characteristic of the older generation of artists he succeeded. To further refute the values of Abstract Expressionist practice, he reproduced and represented his commonplace objects in a style that employed the impersonal method of screen printing, a technique of mass production. Though he neither glorified nor critiqued American consumer culture, but rather depicted it with no evident emotion whatsoever, he insinuated that the extremely personal, individualistic, and idiosyncratic art of the recent past was ancient history.

Even in his unique works of art on canvas, Warhol often used the silkscreen printing process. Like his portraits of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, the ten prints in this exhibition are silkscreens. In addition to prints and paintings, Warhol made more than 700 films. His studio, known as The Factory (lest his self-identification with industrial processes go unrecognized) became a popular New York hangout for other avant-garde artists, young and curious passers-by, debutantes, and a range of alternative types during the 1960s and ’70s.