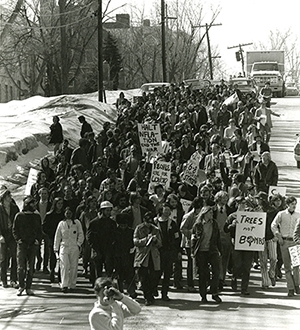

Campus Unrest in the '60s and '70s

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. — When Torie Osborn arrived at Middlebury in the fall of 1970, she thought she was entering “an intellectual hotbed of leftist radicalism.” Instead she found “a bunch of people standing around, tossing Frisbees and talking about the ski season.”

Downhearted to think she had made a mistake by transferring to Middlebury from Barnard College, Osborn soon met a senior named Steve Early who taught her how to organize a movement on campus. Early had helped coordinate the campus-wide student strike the previous spring in direct response to the Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970.

Early ’71, Osborn ’72 and Dennis O’Brien, the Dean of the College from that era, came together for a wide-ranging discussion on January 22 titled “Middlebury in the 1960s: Student Resistance and Social Change.” Held in Dana Auditorium in connection with the student-led Winter Term course “A People’s History of Middlebury College,” the panel discussion attracted nearly 100 students and alumni.

At one point, when one of the panelists asked how many in the audience had attended college in the late 1960s or early 1970s, about 20 hands shot into the air. The discussion, moderated by Jonathan Miller-Lane, associate professor of education studies, touched on the Vietnam War, women’s rights, civil rights, ROTC, abortion, gay rights, fraternities, and social and economic justice.

In 1971 Torie Osborn co-founded the first women’s rights movement at Middlebury, and one of its first causes was to eliminate curfews for women on campus. (Men had no curfews but women did.) She also organized the “abortion underground,” a group of students who secretly arranged visits to a physician in Montreal where abortion was legal. (Roe v. Wade was still two years in the future.) Osborn’s feminism was galvanized at Middlebury, she said, after a professor during office hours invited her to sit on his lap.

The organizational skills Osborn acquired at Middlebury propelled her to a career in activism that has included eight years as executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and a term as senior advisor to the mayor of Los Angeles to reduce homelessness and poverty.

Steve Early arrived at Middlebury in 1967 and promptly joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) which, he said “was in full bloom at that time.”

“One semester’s worth of ROTC was definitely a radicalizing experience for me. Personally, and with many others, I realized that a better way of dealing with [the War in Vietnam] was to end the war, abolish the draft and kick ROTC off campus, or at least strip it of academic credit,” Early said.

Known on campus as one of the leading student activists of his day, Early recounted details from the student strike of 1970, which was focused on stopping the killing in Southeast Asia and ending “campus complicity with the military,” or ROTC.

To put the Middlebury student strike into perspective for the millennials in the audience, Early said the Kent State incident in May 1970 impelled four million college students to go on strike at 500 different colleges and universities around the country. Fifty of those colleges didn’t reopen again until the fall of 1970, he said calling it “the largest student uprising in U.S. college student history.”Early’s commitment to activism has not diminished in the 40-plus years since he graduated. As an attorney, organizer, negotiator and author (most recently with the book “Save Our Unions,” Monthly Review Press: 2013), Early has forged a career in support of the labor movement.

When Dennis O’Brien came to Middlebury in 1964 as dean of men and member of the philosophy department, there were two hot-button issues on campus: the status of fraternities and the existence of “parietal hours,” i.e., rules regulating visitations of male and female students. “Things were reasonably tranquil in 1964,” O’Brien said, but the Vietnam War combined with the presence of ROTC on campus changed all that.

The shootings at Kent State precipitated the student strike and yet, according to O’Brien, the college administration thought it had the situation pretty well in hand. “We were in the midst of taking a week off to do the teach-ins and talk about the importance of the university in the context of American society. Typical of the academic world we were trying to be intelligent about what we were going to do, but then the burning of a building on campus changed all that.”

Recitation Hall, a wooden structure slated for demolition and located near Carr and Battell Halls, was set ablaze by an arsonist on May 7, 1970. “The fire was enormously upsetting,” the former dean recalled. During the strike “people got angry from time to time and we had words exchanged, but we never had that sense of radicalism and of people being dangerous on campus. In fact after the building burned down, the fire department was convinced they would be shot at by Middlebury students.”

“You may laugh now but it was a very, very tense period,” O’Brien said. After the fire, the administration and students went out into the community to assure the public that they were not in danger, he said. In 1976, after 12 years at Middlebury, O’Brien went on to become the president of Bucknell University and later of the University of Rochester.

The panel discussion facilitated by students Hannah Mahon ’13.5 and Kristina Johansson ’14 concluded with this question from the audience: “What is the end goal of all your activism?” Torie Osborn, the feminist who came to Middlebury looking to kindle her activist urges, answered without missing a beat:

“I would really like to see a regulated and humane form of capitalism that redistributes opportunity so that everybody truly — through a public education system and some kind of a safety net — has a shot at equality.”

Note: The organizers of the panel discussion had also invited a fourth panelist, Delrita Abercrombie ’70, who accepted but was unable to attend due to a major snowstorm in New York City the previous day.

Written by Robert Keren with photographs courtesy of Special Collections