15,000 Letters from an Abolitionist Family Offer Vast Opportunities for Research

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – The Davis Library at Middlebury College is now steward of a remarkable collection of letters from four generations of a Vermont family that harbored runaway slaves and were outspoken supporters of the Abolitionist Movement.

The Robinson Family Letters, an accumulation of 15,000 letters dating from 1757 to 1962, will offer students and scholars a wealth of research opportunities for many years to come. The letters are on extended loan to Middlebury Special Collections from the Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh, Vermont.

Rowland Thomas Robinson (1796-1879) and Rachel Gilpin Robinson (1799-1862) were devout Quakers and radical abolitionists, and were among Vermont’s earliest and most vocal opponents of slavery. Married in 1820, they tended Merino sheep at the family’s Rokeby Farm. At the same time they boycotted slave-made goods and – as the letters attest – sheltered Negro men, women, and children who escaped from slavery in the South.

Will Nash, professor of American studies, is using the letters in his Reading Slavery and Abolition course. “The Robinson letters bring students closer to the anti-slavery struggle than most published texts do, because of their personal nature and their close geographic link to Middlebury,” he said.

In one string of correspondence, Rowland T. Robinson writes to a North Carolina slave owner on behalf of “Jesse,” a fugitive then living at the Rokeby Farm. Jesse wished to purchase his freedom from his former owner, and Robinson contacted the owner to negotiate the transaction.

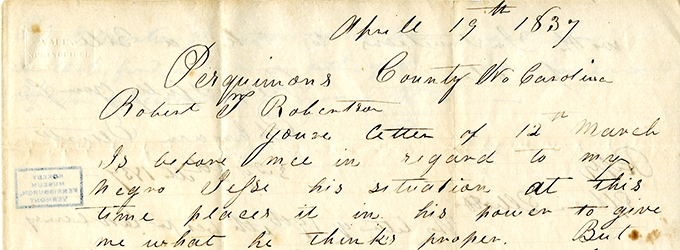

Here is the response he received: “I do not feel disposed to make any title for [my Negro Jesse] for less than Three Hundred Dollars which is not more than one third what I could have had for him before he absconded,” wrote Ephraim Elliott, of Perquimans County, N.C., on April 19, 1837.

See a high-resolution version of the original April 19th letter in a new window.

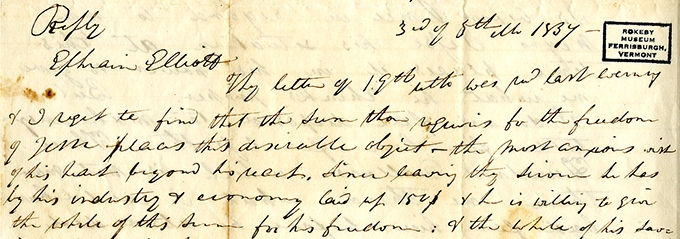

Two weeks later Robinson replied: “Since leaving thy Service [Jesse] has by his industry & economy laid up 150$ & he is willing to give the whole of this sum for his freedom… Please to inform me soon of the result of thy mind in the case & accept my own and Jesse’s since desire for thy prosperity & happiness.”

See a high-resolution version of the original May 3rd letter in a new window.

One month after that, in a letter dated June 7, 1837, Ephraim Elliott declined the offer of $150 to purchase Jesse’s freedom.

The openness with which Rowland Robinson corresponded with a Southern slave owner (and with others on both sides of the slavery issue) suggests a “very different interpretation” than what had been “the prevailing mythology” of the Rokeby Farm and its role in the Underground Railroad, explained Jane Williamson, director of the Rokeby Museum. The letters run counter to stories that “fugitives at Rokeby were in flight, they were hidden in the east chamber or ‘Rokeby Slave Room,’ [and] the entire enterprise was laden with risk and cloaked in secrecy.”

Several letters and other sources present “a picture of former slaves living at Rokeby and working on the farm in relative safety,” Williamson added. The farming of sheep, apple and pear orchards, and feed crops was at its height at Rokeby in the 1830s and 1840s, so there was a need for hired hands.

The topics in the letters extend well beyond offering refuge to runaway slaves. The collection is striking not only for its sheer volume – the letters fill 58 acid-free storage boxes and consume 23.5 linear feet of shelf space – they also concern women’s issues, religion, politics, art, agriculture, temperance, the Civil War, and a host of personal matters.

Notable among the correspondents in the collection are: Clark Stevens (1764-1853), who served in the Revolutionary War; Thomas R. Robinson (1761-1851), the patriarch who started Rokeby Farm; William B. Stevens (?-1863), who died from his wounds in the Civil War; Rowland Evans Robinson (1833-1900), author, illustrator, and commercial artist; and Rachel Robinson Elmer (1878-1919), who was a distinguished artist in New York City.

The potential use for the letters by students, faculty, and visiting scholars is without limit, said Joseph Watson, the preservation manager and archives associate in Middlebury’s Special Collections. Watson is also the “go-to person” for insight into the Robinson family because of his own connection to Rokeby; he was resident caretaker of the museum from 1989 to 1992 before joining the Middlebury library staff.

“We are just beginning to discover the depth and meaning of these primary-source documents,” he said.

The director and curator of Special Collections, Rebekah Irwin, is pleased to have the letters housed at Davis Library where there are climate control and fire-suppression systems, and ample space for researchers to do their work

“The primary mission of the Rokeby Museum is education, which is very different than the need to conserve this valuable old paper. Both tasks are important, but it’s hard for a small museum to do both and do them well, so Middlebury has stepped in to help Rokeby preserve its historical archives.

“For our students, the Robinson Family Letters offer a way to reflect on history and current thinking about race relations. It’s a perfect scenario because here were the Robinsons, a white family in a very white place, Vermont, thinking about race relations and taking action on their beliefs,” Irwin said.

– With reporting by Robert Keren; images reprinted courtesy of Rokeby Museum