Faculty Put ISIS Attacks in Context [video]

Watch the full panel discussion.

MIDDLEBURY, Vt – Professor Erik Bleich was in France on sabbatical when terrorists struck the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris last January. A scholar of race and ethnicity in Western Europe, Bleich interviewed a dozen Muslims in Lyon, where he was living, immediately following those attacks. He spoke with “unemployed young men hanging out on a street corner, a funeral parlor employee, a bearded ‘brother’ who had moved to Morocco, a public official, and a retiree.” He was struck by their unified condemnation of the violence, and even more impressed that last week’s attacks were condemned not only by French Muslims, but also in the less likely quarters of Hamas, Hezbollah, and Islamic Jihad.

Bleich said that before November 13, “it was impossible to imagine an act so horrible that it would impel these three groups to stand with France against terrorism.” That’s no longer the case, he noted.

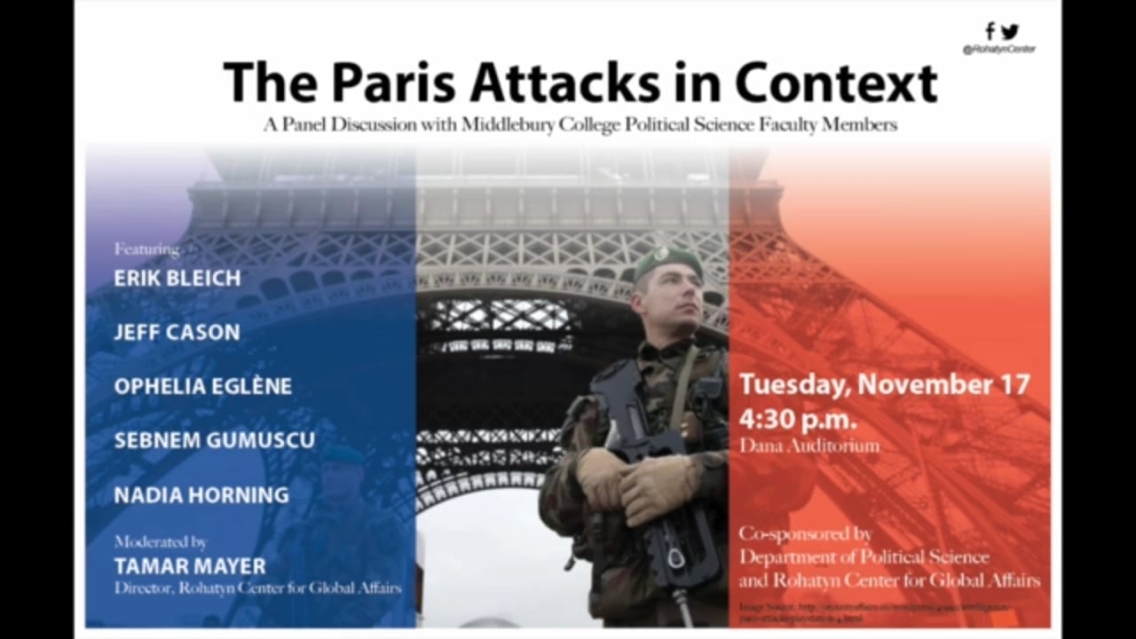

Bleich shared his thoughts during a standing-room-only panel discussion at Dana Auditorium Tuesday that explored the underpinnings of ISIS. Co-sponsored by the Rohatyn Center for Global Affairs and the political science department, the panel offered varying perspectives from five Middlebury political science faculty members, including Bleich, Jeffrey Cason, Sebnem Gumuscu, Nadia Horning, and Ophelia Eglène.

Gumuscu, whose research interests include political Islam and Middle Eastern and North African politics, described ISIS as an unusually complex organization. “Because it is a jihadi organization, violence is a very important part of the organization and its operations. However, it is also a hybrid organization that actually carries a lot of different features such as insurgency, statehood, and terrorism.”

Its origins are fairly easy to trace, Gumuscu said, dating back to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the subsequent insurgency. The insurgency lost momentum during the U.S. occupation of Iraq, but regained support from alienated Sunni tribes when the U.S. withdrew its troops. “We see that this insurgency quickly grew in strength by making a very important and strong alliance with the former officers of Saddam Hussein,” said Gumuscu.

A confluence of factors created favorable conditions for the recent growth and success of ISIS, Gumuscu said. State collapses in Syria and Iraq have allowed ISIS to control huge swaths of land, sizable populations of people, and abundant resources. Individual financiers from the gulf states and porous borders with neighboring countries, especially Turkey, have facilitated trade and mobility of fighters. And ISIS has used social media, especially Twitter, more effectively than any other jihadi organization, as measured by its success in recruiting 15,000 foreign fighters.

The problem of Islamist terrorism, Professor Nadia Horning pointed out, goes well beyond ISIS and is bigger than individual states. Horning began her talk with a sobering map of the major terrorist organizations that have evolved throughout Africa and the Middle East.

“I think that the problem we’re facing today,” said Horning, “has a lot to do with interventions that have no grand strategy, no real political project, but simply immediate goals of flexing muscles, showing strength to a democratic populace that wants to see action taken by their government.” The failed states that result from these military campaigns become breeding grounds for terrorists when very little is under the control of a central government, Horning said.

The Paris attacks have sent shockwaves through the European Union, said Eglène, who studies the E.U. She said that French President François Hollande’s closure of the borders following the attacks has raised concern about the future of the Schengen Area–comprised of the E.U. countries–which does not require passports or border controls among member states. Further, she said, the attacks have created a rift among E.U. nations’ plans to accept the massive influx of refugees. Poland and Slovakia, so far, are rethinking their previous commitment to accept Muslim refugees from Syria. Cason, who spoke in his capacity as dean of international programs, said the incidents in France are a reminder that there is inherent risk in the world and that prosperous nations are not immune to those risks.

During the question and answer period, Bleich pointed out that, while looking at maps and thinking about the large populations under ISIS control might lead to the impression that millions support the terror organization, the opposite, in fact, is true.

Professor Timi Mayer, director of the Rohatyn Center for Global Affairs, who moderated the panel, agreed with Bleich. “The numbers are small,” Mayer said, “and I want to be sure that we go back to the point that you made, and that is that the majority of Muslims don’t support this. They condemn it, and it’s important for us to remember that.”

With reporting by Stephen Diehl; Photos by Todd Balfour