Faculty Voice: The Countries that Gave me a Second Chance as a Refugee

The following piece by Professor Michael Kraus was published on the web site Open Society Foundations on November 23, 2015.

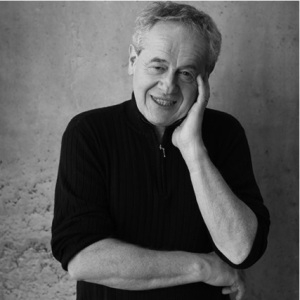

By Michael Kraus

The horrific attacks in Paris occurred in the midst of Europe’s biggest refugee crisis since World War II. Now some in Europe and the United States are using these attacks as an excuse to close their doors to people fleeing terror and violence in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere—terror and violence perpetrated by the likes of those who committed the crimes in Paris.

The reaction in Europe and the United States was very different four decades ago when I was fleeing persecution.

I was forced to leave Prague at the age of 19, a few months after 500,000 Soviet troops invaded what was then Czechoslovakia. Their aim was to stop the Prague Spring, a period of liberalization in which rights and freedoms expanded under reformist Alexander Dubček’s leadership.

On the morning of the invasion, August 20, 1968, I was at the post office where I had a summer job. We were listening to Czech national radio when they announced, “If you hear the national anthem, it means this is the end of our legal broadcasting.” Seconds later, the national anthem started playing. I looked around me and saw my coworkers—women the age of my mother—crying. Through the window, we could see Soviet tanks occupying our street. At that moment, I felt truly lost and afraid.

I was a passionate believer in what the Prague Spring represented, and that same week I joined the numerous spontaneous acts of civil disobedience directed at the Soviet army. There was some violence, too—I remember seeing young people covered in blood carrying the Czechoslovakian flag. Our government called the invasion illegal but soon our top leaders, including Dubček, were arrested and taken away. Suddenly we felt that we were left with no direction.

In the months following the invasion, between 80,000 and 100,000 people left the country. I managed to leave as well after receiving an invitation from a British school to study there. Many British schools provided young Czechs such as myself safe haven—indeed, this same school had provided asylum to my cousin during World War II. History was repeating itself.

The school gave me an opportunity to start anew. I spent about eight months there before obtaining political asylum in the United States. I worried I might never see my parents again, and it turned out I was nearly right: it took 10 years. I wouldn’t meet my younger siblings, who had stayed behind, until 14 years later. That’s the price you pay for being a refugee.

Eight years after my departure, in 1977, I was sentenced in absentia to a year in prison because I had apparently left Czechoslovakia without government permission. My older sister, my brother, and my brother’s wife, also refugees (in Colombia and Germany, respectively), also received sentences. It was a tactic the authorities used, I think, to extract resources from refugees—the verdict meant that we forfeited all our property.

Since then, I have gone back to visit and compared notes with former classmates who stayed behind. The regime went from bad to worse after I left. Several hundred thousand people were fired from their jobs for political reasons, and their children were often denied access to higher education. Hundreds of authors, journalists, and artists were blacklisted, their works banned. The regime destroyed many members of my generation in terms of their ability to make something of themselves.

I was very fortunate that I was given a second chance thanks to the hospitality of other countries—people who gave a total stranger the opportunity to start again. The kindness of this simple act made me feel obligated to make the very best of my new life, not just for me, but for all of those who were left behind.

In my quest to better understand what happened to my country, I was drawn to politics and international affairs. Today, I am a university professor who teaches those subjects to a new generation. It brings me joy to work with young people who are now around the age I was when I left my homeland, and to analyze the impact, for better or worse, that politics can have on people’s lives.