The Art of Japanese Tattoo

[view:embed_content==538396]

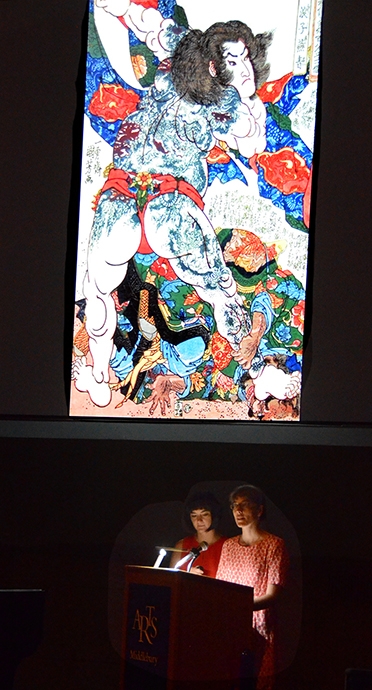

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – Two college professors who met 11 years ago as Level 1 students in the Japanese School returned to Middlebury on July 20 to deliver an illustrated lecture on the art of tattoo in Japan.

The presentation by Sarah Laursen, now an assistant professor of art history at Middlebury College, and Brigid Vance, now an assistant professor of history at Lawrence University, was given in connection with the summer-long exhibition “Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in the Modern World” at the Middlebury College Museum of Art.

The exhibition also included a live, daylong tattooing demonstration on July 9 in Rehearsals Café at the Mahaney Center for the Arts (MCA), followed by a reception and sake bar.

Laursen, who holds a second appointment at Middlebury as curator of Asian art for the museum, brought the “Perseverance” exhibition to campus and coordinated activities with the Japanese School. She also obtained Vermont licensing for the “Tattoo Shop” at the MCA and retained the services of San Francisco tattoo artist Nakona MacDonald and his subject. More than 300 people visited the museum and the adjacent tattoo demonstration on that summer Saturday.

The director of the Japanese School, Kazumi Hatasa, introduced Professors Laursen and Vance to the audience in MCFA’s Robison Hall and referred to them by their Japanese School names – “Loosen” and “Bansu,” respectively – adding the honorific “sensei,” or teacher, to their names.

Laursen and Vance walked the audience through a brief history of tattoo. The earliest evidence – Ötzi, a mummy from more than 5,000 years ago – was found in Europe, and his tattoos are believed to have been for therapeutic purposes, the professors said. Tattooing was also found in Siberia dating back 2,300 years ago with stylized images of birds, fish, and other animals thought to bring good fortune in the hunt.

Tattooing began in Japan in the third century, and irezumi – or entering ink into the skin – has long been practiced in Japanese culture for protection, punishment, romance, and other purposes.

The Edo period from 1603 to 1868 was a prolific time for tattoo art in Japan, the professors said. An era of peace, economic growth, and social change, it fostered the creation of elaborate and colorful woodblock prints that had a lasting effect on tattoo art.

The presenters showed slides of Japanese body suit tattoos and discussed the practice, which is featured prominently in the current museum exhibition and originated during the Edo period.

Laursen, who involved her spring 2016 museum studies class in the marketing, design, and layout for the summer exhibition, also explained how Japanese tattoo artists still use “traditional mineral pigments and vegetable dyes mixed with diluted rice paste” to produce their colors.

“Black outlines use lampblack, which was made from soot. Red was made from iron sulfate or safflower petals, green from vitriol, and blue from ultramarine or indigo, And the use of white was rare because it was almost impossible to see,” she said. Irezumi was an underground art form that was traditionally taboo in Japan, but it is now gaining wider acceptance internationally, Laursen added.

The Middlebury Museum of Art exhibition “Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in the Modern World” runs through August 7. Originally organized by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, the exhibition photographer was Kip Fulbeck and its curator Takahiro Kitamura. The Middlebury museum is open to the public Tuesday through Sunday, and is always free of charge.

– Photos of Tattoo Shop and exhibit by Yeager “Teddy” Anderson ‘13.5; with reporting and lecture photography by Robert Keren