A Student’s Animation Sheds New Light on a Professor’s Biology Research

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – Biology Professor Grace Spatafora just happened to be standing next to animation studio producer Daniel Houghton when she saw a student animation detailing molecular processes in the Lyme disease–causing bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi. Spatafora, who studies the bacteria that cause tooth decay, said she turned to Houghton and said, “This is tremendous. I would really love to have something like this for my own teaching and research.”

Houghton knew that finding the right student collaborator for Spatafora’s project could take some time (the creator of the Borrelia animation was graduating). The collaborator would need to have a science background and be eager to try their hand at science animation.

“A student who wants to make cartoon comedy,” he pointed out, just wouldn’t be the right fit.

By the next fall, Michelle Lehman, a junior majoring in neuroscience, took her first class in animation and fell in love with it.

Combining art and science through animation, said Lehman, “is what fuels me.”

Houghton brought Lehman and Spatafora together.

Their collaboration—a three-minute-and-23-second, 4,872-frame animation of key aspects of Spatafora’s research—debuted on campus at the 2018 Spring Student Symposium. Next week, it will premiere to a wider audience when Spatafora presents at the Mark Wilson Conference, an annual gathering of oral immunologists and microbiologists.

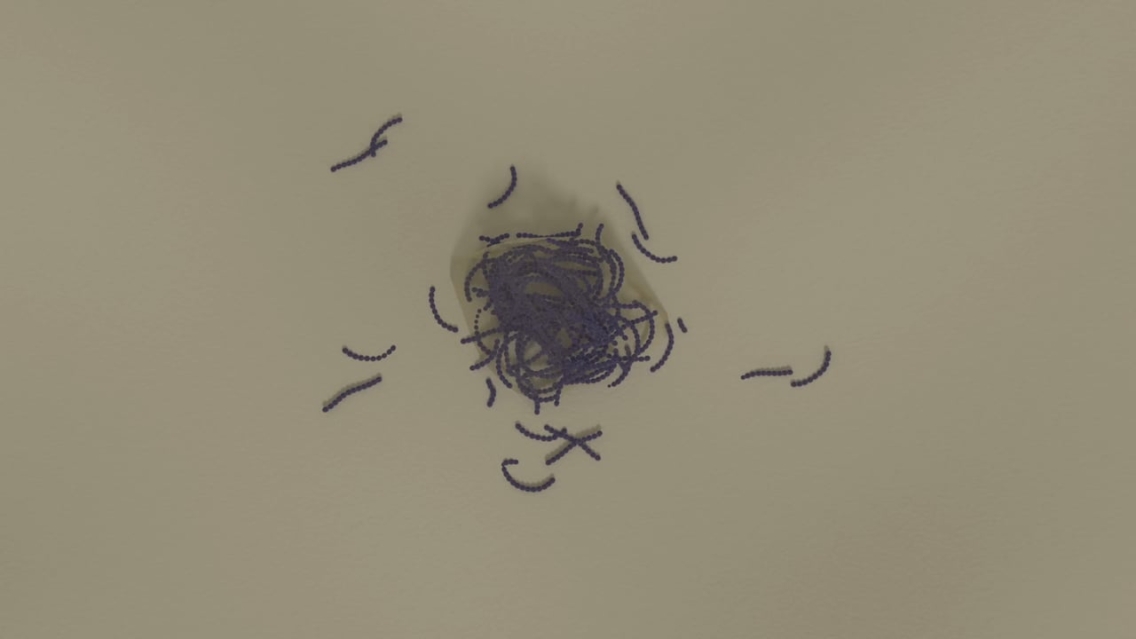

The animation zooms in on a “matched set” of manganese-regulating proteins in Streptococcus mutans, a bacteria that causes dental cavities. Manganese plays a role in overall cell vitality and in S. mutans’ virulence, including its ability to make “biofilm” (dental plaque) and its ability to resist antimicrobials. One set of proteins, called SloABC, allows S. mutans to bring manganese across the cell wall; another, called SloR, blocks manganese intake. Spatafora’s research is uncovering the precise mechanisms by which these processes occur.

Lehman’s animation brings the viewer inside the cell, to watch these processes as they unfold. It starts with the tooth, closes in on a cluster of bacteria, skims above the cell wall of an S. mutans organism, goes inside the cell and then focuses on the specific site on the DNA where the two proteins interact to bring in or block manganese.

What’s startling is the orderliness and beauty with which Lehman portrays these as-yet-not-entirely-seeable subcellular processes. For the nonscientist, it’s a bit like an undersea adventure documentary, the way the eye is led through and given a shifting vantage point on an unfamiliar yet intriguing landscape.

The opportunity to work with Spatafora, winner of three National Institutes of Health R01 research grants (one of a handful of liberal arts researchers to be so distinguished), taught Lehman a lot about the kinds of communication needed to create a successful science animation.

The round S. mutans bacteria cluster together like beads on a string.

“They look like worms,” said Spatafora.

“So my bacteria, at one point,” said Lehman, “were squiggling around like worms. And that’s just not what happens. At all. They don’t move like that. But because I was having so much fun with the art, you know, I was almost forgetting about the science. So I was learning to balance that.”

Initially, Spatafora wanted the animation to be in black and white—because we mostly don’t know the colors of the various molecular and biochemical components within the cell.

“I don’t like color because I think that it falsifies the science,” said Spatafora.

But Lehman had a strong sense that color could be used to describe the very processes that Spatafora is interested in with greater specificity.

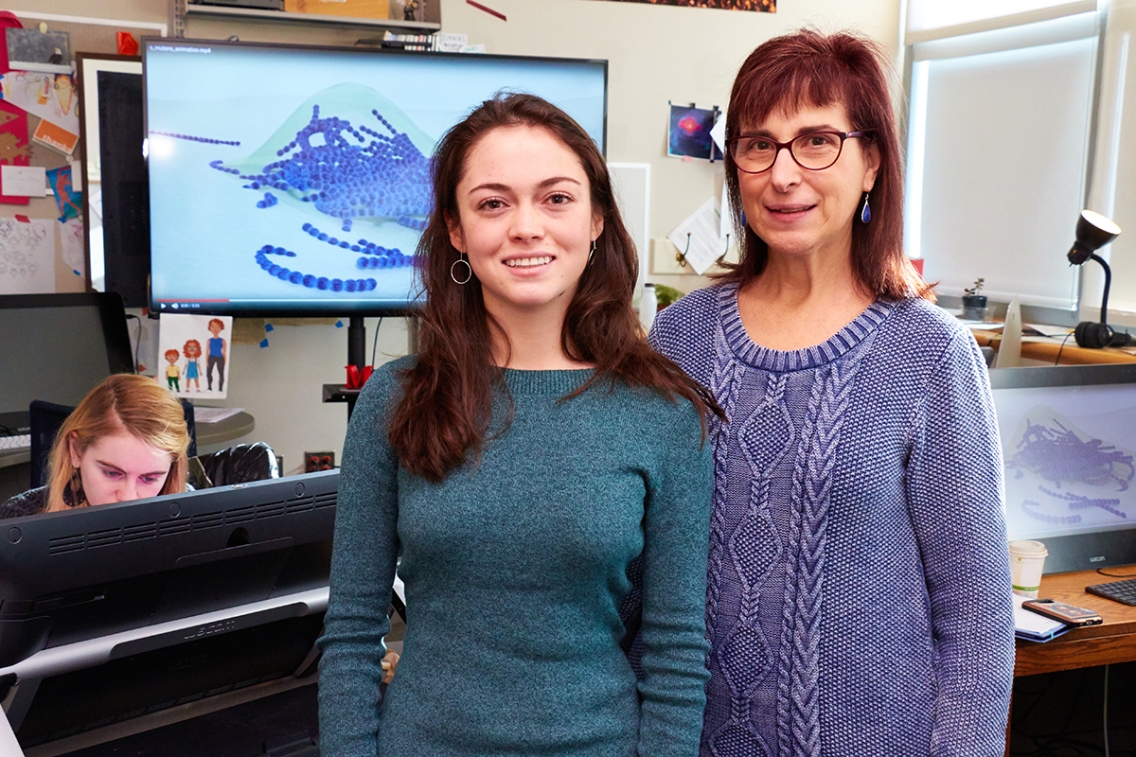

Michelle Lehman ’19 with biology Professor Grace Spatafora at the animation studio in Davis Family Library. Lehman created an animation showing key aspects of Spatafora’s research on the genetic underpinnings of dental cavities.

“So we had a conversation,” said Spatafora. “I said, ‘I understand. I’m okay with color, but none of these rainbow colors.’ A lot of video that’s already out there is so artificial… . What makes this video so unique is it really tries to recapitulate what we think everything looks like. Everything down to the very texture of the protein, the surface of the bacterium, the fluidity of the membrane, the rigidity of the cell wall. Everything is as real as we can make it… . So that was one thing we negotiated, and she did a great job. She picked subtle colors that helped inform the onlooker without distracting from the reality of what was playing out.”

Perhaps most interesting, the animation prompted Spatafora to frame new questions about her decades-long research. For example, SloR binds to the DNA in three regions to block intake of manganese. Based on her own research, Spatafora knows which region binds SloR first, but not which regions bind second and third. But because the animation unfolds in real time, Lehman had to assign an order.

For Spatafora, talking through this part of the animation highlighted that lack of understanding and reinforced that “we need to do that experiment.”

For Lehman, the collaboration has opened a door onto a new life path and reconnected her lifelong love of art and science.

Lehman had pursued studio art seriously in high school, including being selected for a yearlong mentorship with Colorado-based sculptor Nancy Lovendahl. But at Middlebury, Lehman eschewed art for science, focusing on premedicine.

Occasionally, though, she let a little bit of art break through. As a first-year, she took a winter term Introduction to Painting course.

“I just wanted to paint all J-term—and I did,” said Lehman. “I would actually pull accidental all-nighters where I was just in it, and all of a sudden the sun was rising, and I was like, ‘Did I just stay up all night painting?’ I could do the same with this stuff [animation] too, except it strains your eyes.”

She also offered occasional outdoor painting sessions through the Middlebury Mountain Club and minored in art history.

“I was always trying to keep art in my life,” said Lehman. “I had to incorporate it somehow because I missed it.”

Then, as Lehman described it, “the stars aligned.” Signing up for fall 2017 classes, she noticed Houghton’s course on 3-D computer animation.

“I just stumbled upon it and was like ‘Oh, this is interesting. It’s kind of techy, it doesn’t take up too much time.’ I didn’t even know what animation was. Then I was blown away, I loved it so much.

“People always talk about ‘Oh, this would never happen to me,’ like that one class that changes your life and kind of sets you on a path. And it did happen to me. I fall into that cliché,” said Lehman, laughing.

Since that first class, Lehman has been a mainstay in the animation studio, working as a TA, mentoring a local middle schooler, acting as studio intern, pursuing her own projects through independent studies. She spent her final winter term creating animations for the Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey; the animations will be used to help experts-in-training learn to identify different intercontinental ballistic missiles. Other animations in the works include ones for the Hill Lab at Dartmouth and for Middlebury’s Open Door Clinic.

“It’s really wonderful to interact with someone who is both capable of understanding the substance but then also has this artistic capability,” said Jeffrey Lewis, a leading expert on North Korea’s nuclear program and director of CNS’s East Asia Nonproliferation Program.

Lehman credits Houghton (a 2006 Middlebury graduate and award-winning animator, who describes his own path to animation as less than straightforward) for making the animation studio a place where students can “pose a project, pursue it, create it, and execute it… . I think it’s really important for Middlebury to create and promote these types of spaces.”

Houghton said the studio offers a way of building visual literacy—using images to explain and comprehend the world—in an interdisciplinary setting.

“In the animation studio, we’re trying to showcase how scientists and artists and scholars can connect meaningfully through project work that happens to involve digital tools,” said Houghton. “Animation can become basic communication in any discipline, and it—like writing—can define what’s sayable. Certain things resound when put into words; certain ideas only live in visual spaces.”

By Gaen Murphree, Photos by Todd Balfour, Animation by Michelle Lehman ’19.