New Book Offers Fresh Insights on Chicago Freedom Movement

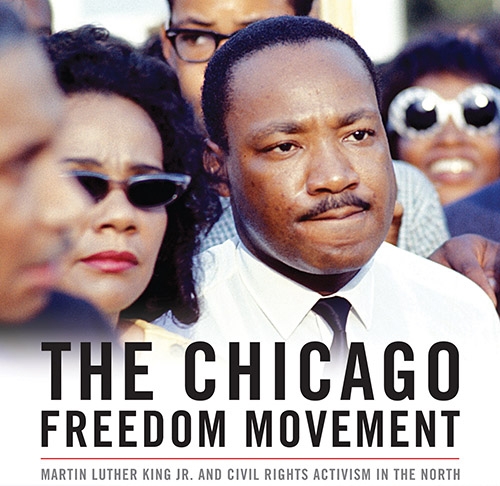

Professor of History Jim Ralph collaborated with three other edtors on a new book, The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North, which will be published on Apri 5. In the Q&A below, Ralph reflects on topics ranging from the movement’s impressive legacy to its role in King’s career.

Why is it important now to take a fresh look at the Chicago Freedom Movement?

Our new book coincides with the 50th anniversary of the Chicago Freedom Movement. The Chicago campaign, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., addressed directly issues and problems that still challenge us today — inequality, poverty, racial division, and the sense of powerlessness among those outside of privileged circles. One can argue that the Chicago Freedom Movement speaks more to our own times than Dr. King’s more celebrated campaigns in Birmingham and Selma.

Some have viewed the Chicago Freedom Movement as largely ineffective but your book describes its impressive legacy. Why have people overlooked this?

The prevailing view of the Chicago Freedom Movement was established by late August/early September 1966, when reporters and news commentators declared that Mayor Richard J. Daley had been able to best the efforts of civil rights forces in Chicago. It is true that the momentum of the nonviolent civil rights movement faltered in the summer of 1966 with the rise of the Black Power impulse and the seemingly modest returns on the Chicago movement’s open-housing campaign.

But the Chicago Freedom Movement activists launched many initiatives from 1965 to 1967, most of which garnered little publicity, and with the aid of historical hindsight and with careful research, the contributors to our book were able to trace the enduring impact of many of those initiatives. For example, the work of Chicago activists helped to transform the tenant unions movement and mortgage lending policies in the country.

There were other even more visible repercussions of the Chicago movement. Our book shows the direct connection between the Chicago Freedom Movement and the election of Barack Obama as president in 2008. Obama, who grew up in Hawaii and who graduated from Columbia University, went to Chicago in the mid-1980s as a community organizer in large part because of the sense of possibilities in the era of Harold Washington as mayor of Chicago. Washington, the first black mayor of the Windy City, drew on the advice and support of former Chicago Freedom Movement activists and his mayoralty was a direct response to the weakening of the established Cook County Democratic machine, the weakening which the Chicago campaign helped to initiate.

Rehnquist Professor of American History and

Culture Jim Ralph

How does the book give a voice to those who participated in the movement?

The book features the stories and commentary from the prominent and less prominent. Andrew Young, former chief lieutenant to Dr. King and former mayor of Atlanta, and C.T. Vivian, one of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s top strategists, share stories from the Chicago movement, but so too do local Chicago activists like Rosie Simpson and Don Rose, and former SCLC organizers in Chicago like Herman Jenkins and Molly Martindale.

Jesse Jackson contributed an important chapter to our book. Jackson is the key figure connecting the civil rights movement to activism in our own time. The Chicago Freedom Movement launched Jackson as a significant civil rights activist, and it was from his base in Chicago that he sought the Democratic Party presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988. Indeed, without Jackson’s pioneering runs it would have been more difficult for Barack Obama to have succeeded in 2008.

How was the Chicago Freedom Movement different than what Dr. King and his fellow activists had experienced in the South and Washington, D.C.?

The Chicago Freedom Movement — whose stated goal was to end slums — was even more ambitious, one could argue, than the Birmingham and Selma campaigns. The Chicago movement brought together the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King’s organization, and local Chicago civil rights groups.

The scale of the Chicago effort dwarfed that of southern campaigns in that Chicago was a massive metropolis in comparison to Birmingham and Selma. Chicago was also much more ethnically and racially diverse, making the organizing effort more complicated, especially because Chicago lacked the public ideology of segregation that marked the Jim Crow South. A major challenge facing Chicago activists was trying to understand the forces behind segregation, discrimination, and inequality in a northern setting.

But as the open-housing marches in Chicago in July and August 1966 revealed, animosity on the part of many white Chicagoans toward African Americans was as intense as that of white southerners. After a rock struck him on a march on Chicago’s Southwest Side in early August 1966, Dr. King said there was more hatred in that northern city than in the South.

In 1968, the Poor People’s Campaign concluded with protests in Washington, D.C. Dr. King was assassinated in April of that year before the culmination of his last crusade. The Poor People’s Campaign was a direct continuation of his work in Chicago.

What role did the Chicago Freedom Movement play in King’s career as a civil rights leader?

Chicago transformed Dr. King. His experience forced him to address race, poverty, and inequality on a national level more fully than ever before. He also became more insistent on the need for massive social democratic policies.

Was there a Middlebury connection to the civil rights movement in Chicago?

Jean Birkenstein Washington ‘48 helped lead the fight against school segregation in Chicago and the policies of School Superintendent Benjamin Willis. This struggle led to the creation of the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, a coalition of civil rights and community groups, and it was the CCCO that formed an alliance in 1965 with Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to create the Chicago Freedom Movement.

Did any current or former Middlebury students contribute to the publication of the book?

Sam Parnell ’11, Connor Williams ’08, and Devon Wright ’12 all assisted with the research. Scott Bulua ‘07 and Andy Rossmeissl ‘05 developed the initial website that helped promote the 40th anniversary commemoration and our initial thinking on the book project. Samantha Moog ’13 then helped refine the website and current student Leah Lavigne ’16 continues to work on it. Ben Meader ’10 prepared excellent maps.