Panel Offers Multiple Perspectives on Building a ‘Robust Public Sphere’ [Video]

Error message

Could not retrieve the oEmbed resource.MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – What does a robust public sphere look like? Why is important? How do we build one?

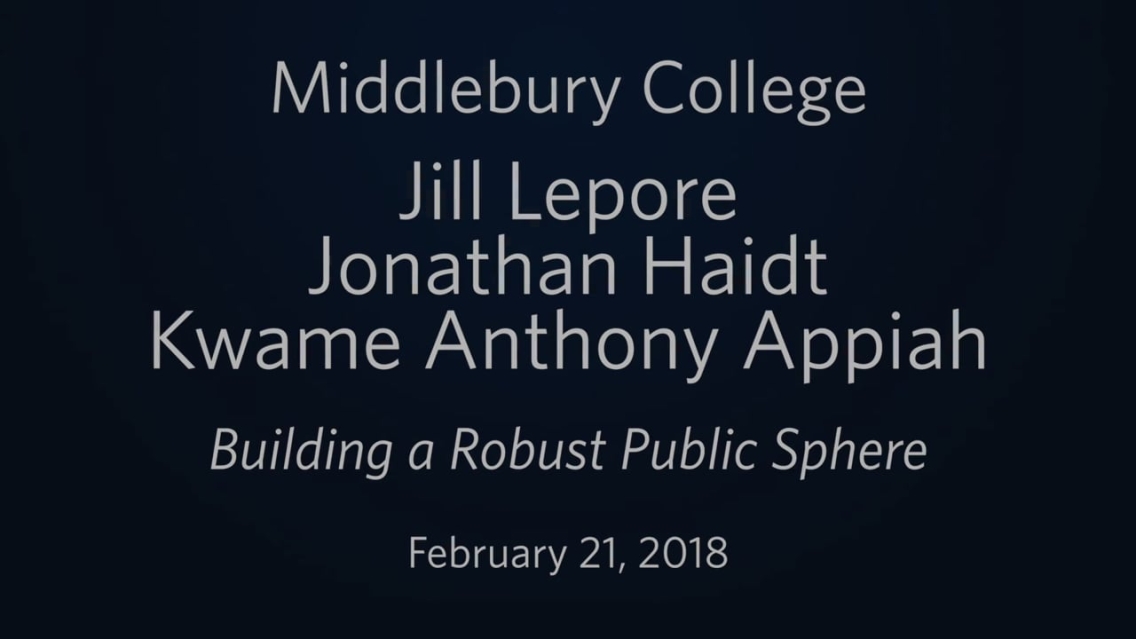

Those were the questions on the minds of three public intellectuals who convened at Middlebury College on Feb. 21 for the latest in the College’s “Critical Conversations” series. The conversation spanned from the writings of John Milton to the philosophy of John Stuart Mill, from social psychology experiments to thoughts on diversity in higher education — and challenged students to think about the echo chambers they might inhabit when living and working among like-minded peers.

The evening brought together noted thinkers and writers from three disciplines: historian and New Yorker staff writer Jill Lepore, who teaches at Harvard; philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, a professor of law and philosophy at New York University; and Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist who focuses on the foundations of morality and who teaches in the Business and Society Program at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

Lepore noted early that the idea that “we learn by disagreeing with people who have different opinions from us” has a long history and deep foundations in the liberal arts. From John Milton to early founding fathers to abolitionists to suffragettes, thinkers and leaders have upheld the idea that free speech and the freedom to argue are fundamental, crucial values. In the mid-20th century, she noted, it was colleges’ willingness to host speakers of different opinions that advanced the civil rights cause — and that also sparked a backlash from those who wanted to limit radical speech on campus.

“That is the long inheritance that we bring to this question,” said Lepore, “generations, centuries of people debating what we learn when we are in college and what we bring from what we have learned in college into the world — and one of those things is how we argue.”

That we argue at all — or at least, that we confront different opinions — is critical, Haidt went on to add later, pointing out that humans are hardwired to seek out information that supports their already-held beliefs. He mentioned research out of Harvard that shows that as people go up in IQ, they become better at reasoning — but only at finding reasons on their side. Ask a group of people who share the same fundamental viewpoint to find truth, Haidt said, and they’ll fail miserably.

And yet put individuals together in the right combinations, and magic can happen. This, said Haidt, is the genius of universities and juries: Well-constructed, they cancel out individual confirmation bias. The group is smarter than the individual.

“A university is special because it is one of the only places where we have institutionalized disconfirmation,” he said. “And if that breaks down, then that whole field of scholarship has broken down, and is not reliable, and cannot be trusted, and cannot be used to give policy recommendations.”

But diversity of opinion is like diversity of any kind — that is, often divisive, as shown in classic social psych experiments. And so, what is the university to do if it should both foster diversity and build robust communities?

Haidt posited two approaches the institution can take while actively engaging in diversifying the college community. In the first, an institution can downplay differences between individuals and instead reinforce that which they have in common, build group rituals, and then — after establishing a group identity — work out differences from a place of trust and mutual respect.

In the other, he said, universities can begin on day one of orientation by talking about differences, giving training in micro-aggressions, and build teams of advisors and faculty and staff who adjudicate conflict. “If we do it that way, we can pretty well expect eternal conflict,” he said.

Haidt, throughout the evening, espoused the view that universities should err on the side of providing too little guidance to students rather than too much — allowing students to work out for themselves what it means to navigate differing viewpoints and arguments. “A lot of the things we do in college to help our students are exactly the opposite of what we should be doing,” he said.

As the evening wound to a close, students looked to the panelists for advice. “How do you think we can break down these echo chambers and these silos of homogeneity?” asked Alex White, who had recently arrived on campus as a ‘Feb.’

“This problem looks intractable at this moment, but when I was growing up, all we ate was fast food,” said Lepore. “People were like, ‘Why do we feel sick all the time?’” And now, she said, we know we can’t eat like that and expect to live a healthy life.

“These questions for how you lead your own life, in terms of what are your obligations to people around you who have different ideas, are actually certainly more important than whether you’re getting enough hours at the gym,” said Lepore. “You can actually think about them in similar ways, that it has to do with how you bring your best self to the world, and that does require coming up with your own ethic with regard to how to escape the echo chamber that you yourself are in.”

Continuing with that metaphor, Haidt pointed out that, just as junk food is engineered to be satisfying, so too is social media. The result? “You have to work a little harder to get a nutritious diet of information coming in,” said Haidt. “And it’s not just information coming in, it’s also social interactions.”

Here’s where universities can play a role, said Appiah. Make it clear that these are places where everyone is welcome. Where people can try out views within the context of mutual trust. Build social capital by doing interesting, meaningful work together. Once those relationships exist, “then you can turn to the hard stuff.”

Said Appiah, “A residential campus is the ideal place to do that, but it takes work.”

Story by Kathryn Flagg; Photos by Todd Balfour