Knoll Interns Dig into Food Systems and Summer Harvest

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – Walking up the back hill at the Knoll one afternoon, Food and Garden Educator Megan Brakeley noticed something odd about the garden’s lone tamarack.

“There were all these eyes looking at me, all these little black beady heads,” said Brakeley, who had paused to admire the tree’s soft branches only to realize “It’s alive!”

She then called her crew of summer interns around the tree to ask, “What are these creatures, and what should we do about them?”

“There were clusters of larvae on little branches on the tamarack, and it was funny because there they were, just falling from the tree,” said Knoll intern Thibault Lannoy.

For Lannoy, a physics major and rising junior, these impromptu moments of problem-solving are one of the best parts of working at the Knoll.

“A big part of the process is us learning as a group and exchanging information… . We’re all there to ask questions,” said Lannoy.

After a little online and print research, the group determined that they were looking at a sawfly infestation—and catching the larvae at the very moment that individuals begin to drop to the ground to pupate.

After that, it was on to squishing.

Brakeley sees the summer Knoll internships as a place to better understand natural systems and grasp technical skills like how to use or maintain a tool properly—as well as a place where students have the freedom to make mistakes, figure things out as they go, and build their own powers of observation and decision making while they put in the hours necessary to keeping the garden beautiful and bountiful.

Students founded what was then called the “Middlebury College Organic Garden” in 2002. Even then, it was affectionately referred to as “Kestrel Knoll” for the flights of raptors often seen overhead. The garden was officially renamed the “Middlebury College Organic Farm” in 2011, and then “The Knoll” in 2017.

“First and foremost, we were motivated to grow food,” said cofounder Bennett Konesni ’04.5. “We wanted the experience of planting a seed, caring for it, and eating whatever grew. We wanted to eat that food in the dining halls and share it with our friends, professors, and neighbors.”

Students also wanted to learn more about food systems, said Konesni. A Food Studies program joined Middlebury’s academic offerings in 2015. And, indeed, said Food Studies professor and program director Molly Anderson, “One of my things is to make sure that no student goes through the program without being aware of the Knoll and having visited.”

Konesni also related that students founding the Knoll simply wanted a place to connect with nature, with each other, and just be.

“Founding the Knoll really came from a need—a hunger—of just needing to get out of our heads and back into the earth,” said Sophie-Esser Calvi ’03, who now oversees the Knoll as associate director for the Global Food and Farm Program.

That spirit remains alive today.

“I knew that I wanted to be outside, and I wanted to be working with either plants or animals as part of my major, and also thinking about sustainability and how you can favor agricultural practices that are more sustainable,” said conservation biology major Theo Henderson ’20.

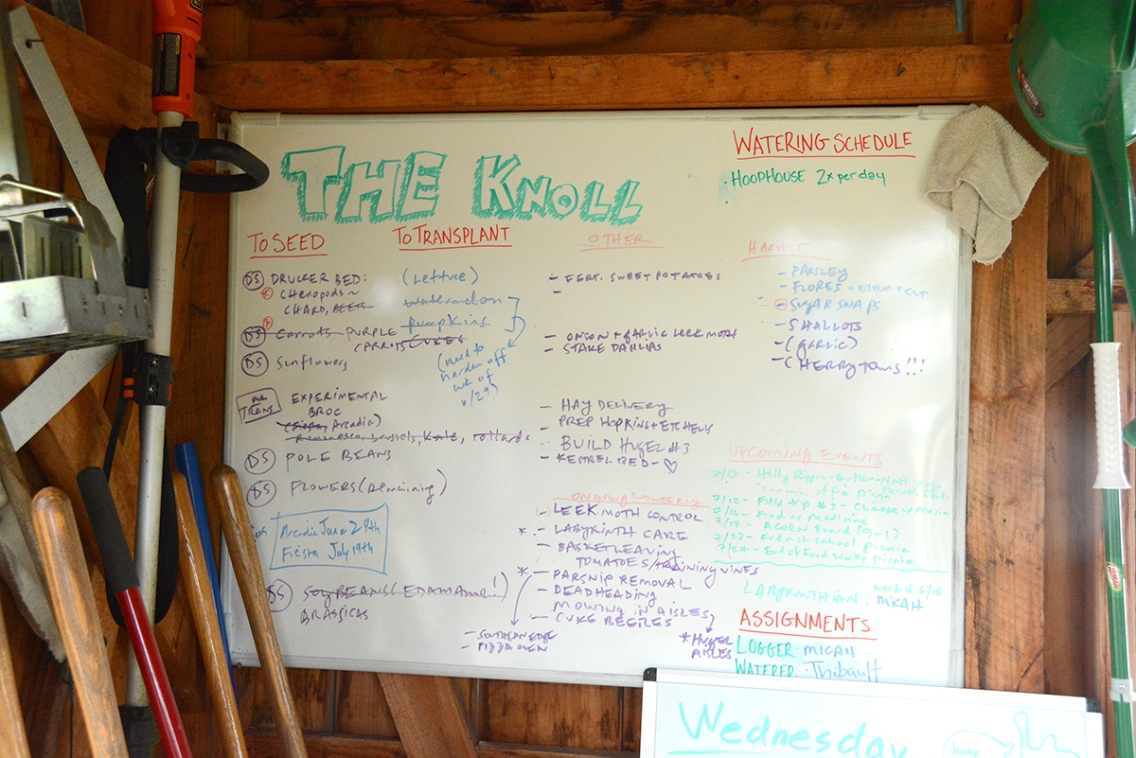

Micah Raymond ’21 harvests shallots at the Knoll.

A recent morning found this year’s Knoll interns hard at work, harvesting chard. All four worked companionably, sometimes in silence, sometimes chatting, carefully breaking off the outer leaves, bundling the chard with rubber bands, then plunging the bundles into a waiting bucket of water. Yellowed or decaying leaves went in the compost bucket. All kept a sharp eye out for insect eggs or damage or other evidence of pests. Off to the east, five turkey vultures circled overhead. Bees buzzed in and out of flowers, drawn to the purple poppies, especially. The air erupted constantly in tweets and chirps and twitters.

The day before—gray and rainy—saw the considerably less pastoral task of weeding out invasive wild parsnip, whose yellow blossoms found along roadways throughout the state are notorious for causing painful rashes and blisters.

“You should see us gear up,” quipped rising sophomore Micah Raymond. “We look like ghostbusters.”

Raymond also noted that one of the best parts of the work day is the “300-footers,” a term coined at a nearby organic farm for questions that can occupy a work crew weeding a really, really long row of vegetables.

“We pose these questions that are like, ‘What would you do if you all of a sudden had a million dollars?’ You can donate it, but you couldn’t invest it… . Or ‘If you had a superpower, what would it be?’ or ‘What is a weed?’”

The bulk of the food raised at the Knoll goes to local nonprofit HOPE (Helping Overcome Poverty’s Effects), which runs the county’s largest food shelf. The rest goes to dining services, local restaurants, and Weybridge House, where the students in the summer FoodWorks program (which includes the Knoll interns) cook, eat, and live.

To get a wider perspective on food systems issues, interns go on weekly field trips to local farms and other places of significance. Last Wednesday, for example, they visited a certified organic vegetable farm with a 191-member CSA; a farm that raises grass-fed, grass-finished beef, using carefully managed pasture rotation practices; and the HOPE food shelf.

“Seeing the whole HOPE operation just makes me excited to get our food out,” said intern Raine Ellison ’19, who said she finds peace of mind in knowing she’s making a contribution to battle hunger locally.Raymond, who volunteered in a local community garden in middle and high school and is one of the more experienced gardeners on this summer’s crew, said that because their dad is a chef, they’ve always thought about food. But this summer, growing food, looking at local food systems, and living in Weybridge House, has got them thinking about food in new and deeper ways.

“We can seed something and then watch it grow and then we harvest it, and then we cook it, and then we eat it. We see the entire process of meals that we make, which is really exciting,” said Raymond. “People are totally, completely disconnected from the food system. Even if it’s a local food system, they don’t necessarily know where it came from or how it got there or where that person got that. It’s like the chain is kind of cut short. But if you actually know the amount of energy and water and care that went into that thing, it makes you super grateful and almost patient and slower when you’re eating it.”

By Gaen Murphree; Photos by Robert Keren