Middlebury Junior Discovers 'Archaeological Glory' in Cyprus

MIDDLEBURY, Vt. – The thrill of uncovering a 2,200-year-old Greek tomb in Cyprus and then crawling inside to find precious relics has opened the eyes of a Middlebury junior to the field of classical archaeology

Magnus Cleveland ’20, a classics major with a minor in museum studies, said the month he spent interning with a New York University–sponsored dig in the Mediterranean last summer was “by far one of the most rewarding experiences” of his academic career.

“The opportunity to apply my traditional education to the practical work of exploring the material culture of the ancient world has helped shape my passion and aspirations,” he said. “I went to Cyprus hoping to explore what some of my options will be after I graduate with my Classics major.”

The Lockport, N.Y., resident soon realized that “the only way we can get new information about the ancient world” is through archaeological digs like the one he joined in Cyprus. “Discovering the daily objects that people used more than 2,000 years ago, and holding them in your hands, was an indescribable experience. It gave me a strong sense of intimacy into the lives of an ancient people.”

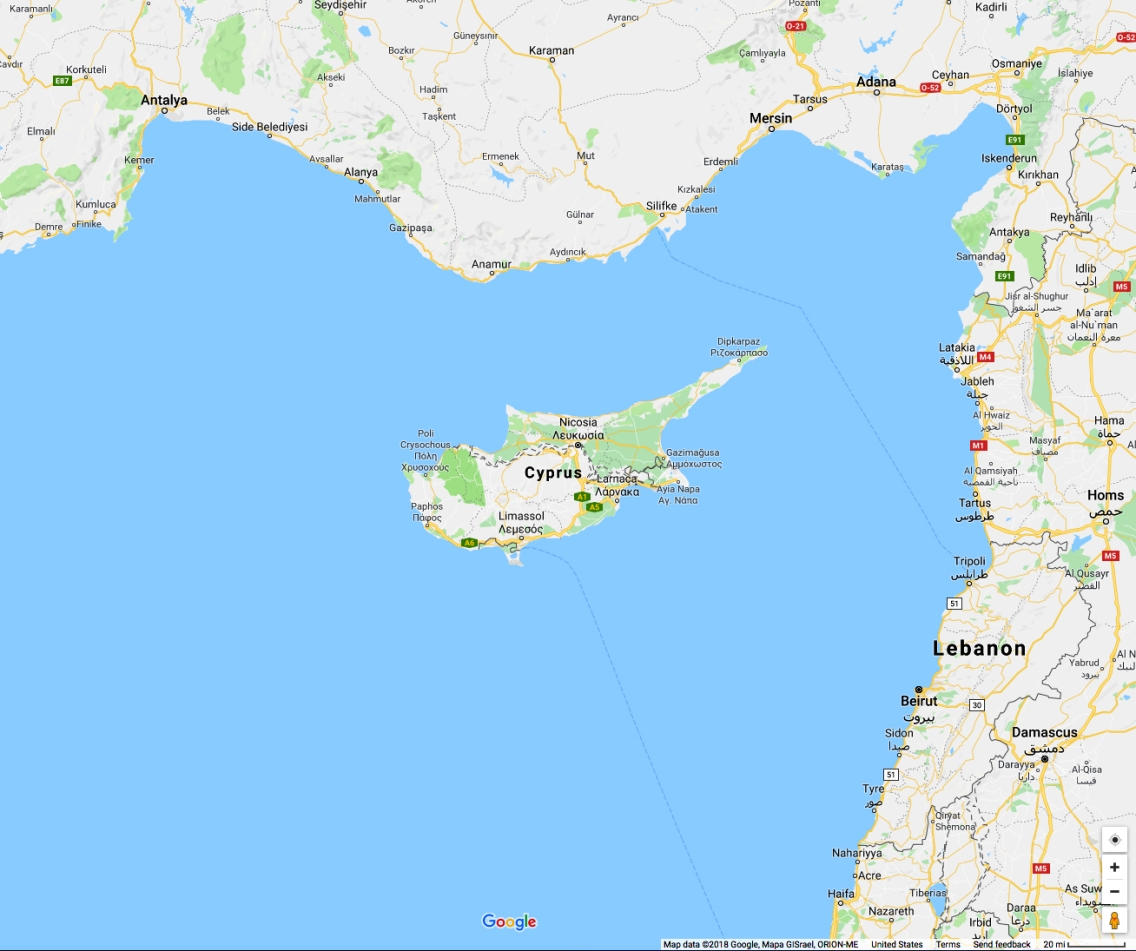

Cleveland was invited in 2018 to participate on the archaeological expedition that has excavated in the region for more than 20 years. Cleveland joined a team that explored a vast necropolis—i.e., a cemetery containing numerous below-ground burial chambers—on the western shores of Cyprus.

“The first big discovery we had was when we realized that what we had been digging for days was an actual tomb,” the Middlebury undergraduate explained. “We were more than two-and-a-half meters down when we came to what appeared to be the top of a door. We eventually got it open enough to see what was inside, and the archaeologist on site—an expert in Hellenistic tombs—looks in and says, ‘This is the oldest tomb in the cemetery!’”

Eventually the team was able to crawl into the tomb and begin the systematic process of taking photographs and documenting every object excavated inside. Cleveland said archaeologists on site were able to date the tomb to between the fourth century BCE and second century BCE based upon the position of the tomb’s loculi (compartments that hold bodies) and the pottery that had been used in the occupants’ funeral rituals.

“At that point, everyone was celebrating what we had found,” Cleveland said. “There is a degree of archaeological glory to working on a dig like that. It was a feeling I had never had before.”

This spring, the junior is hoping to experience more archaeological glory when he enrolls in the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome for a semesterlong program operated by Duke University.

Cleveland plans to follow up his studies in Rome by joining an archaeological dig in Italy “to gain some firsthand experience with the Roman portion of ancient civilization.” All of these encounters in the Mediterranean have led Cleveland to consider undertaking an independent senior project next year, perhaps on the subject of ancient food culture.

“That second when you start coming into contact with the ancient world in a very physical and personal sort of way—that was a really great moment for me. I was in Cyprus on the dig when I realized that [Greek and Roman archaeology] was something that I might really enjoy doing for the rest of my life… . It’s a way to combine my interest in the classics with something very cool and very concrete.”

Cleveland’s faculty advisor for museum studies, Professor Pieter Broucke, spoke about the value of field experiences. “For undergraduates like Magnus, field work in classical archaeology presents extraordinary opportunities. Not only do students get to work with primary sources, they actually help find the primary sources because that’s what archaeology is all about: trying to fully understand ancient civilizations.

“And the best way to learn about archaeology is to actually do it and experience firsthand what it is to discern changes in soil color, handle fresh pottery shards, get a sense of the weight of architectural blocks, feel the heat of the sun, and take in the smell of the excavation trenches. In terms of place-based experiential learning, it doesn’t get much better than that.”

Broucke, who also serves as associate curator of ancient art for the Middlebury College Museum of Art, added, “Ancient objects do not come out of the ground with labels. Interpretation, therefore, is an important aspect of what we do, and it is great to involve students like Magnus in that process.”

Cleveland was quick to point out that the tombs and everything found inside them “are the property of the Cypriot people” and that none of it belongs to the archaeologists.

“We are there working with the government’s permission, and we are not allowed to take a thing,” he said. “We are required to maintain detailed notes because anything that comes out of the dig will have great value, and it’s our job to make certain that value stays with the entities who are the inheritors of that cultural tradition.”

Cleveland was housed with other students in a small hotel in a seaside town, while the dig’s faculty and staff—including Broucke—were accommodated at a nearby villa. “It was a great communal environment,” Cleveland said. “We all had our breakfasts and dinners together, and there was always plenty of lively conversation.”

Magnus Cleveland received financial support from a grant administered by Middlebury’s Center for Careers and Internships to help cover the cost of his unpaid internship in Cyprus.