S4 EP 3 - Big Tech and Its Populist Critics

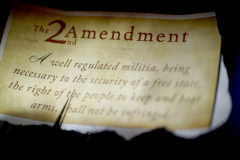

What are some of the common critiques that American populist politicians—on the Left and the Right—lodge against Big Tech? How valid are their critiques? In this episode political scientist Gary Winslett discusses his newest book project—“Big Tech and Its Populist Critics”—which examines populist critiques of Big Tech giants like Apple, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and Google. While Right-wing populists criticize Big Tech for suppressing “free speech”— and Left-wing populists target economic concerns and these firms’ monopolistic practices—Winslett explores these issues, questions the validity of populist critiques from both political sides, and advocates for a “dynamist” approach to public policy that promotes risk-taking, innovation, and a positive outlook towards technological progress.