Conflict Transformation

- Good evening everyone. Before we get started, our crowd control manager, Selena, would like to offer you some information about the exits.

- [Selena] Yes hello everybody. My name is Selena and I’ll be your crowd control manager. So just to keep in mind the exits, there’s an exit here, exit right here, one in back, and the one to my right, which might be your left. Keep in mind to please keep aisles clear of any personal items or any debris just in case of an emergency, please. And I hope you guys have a lovely night.

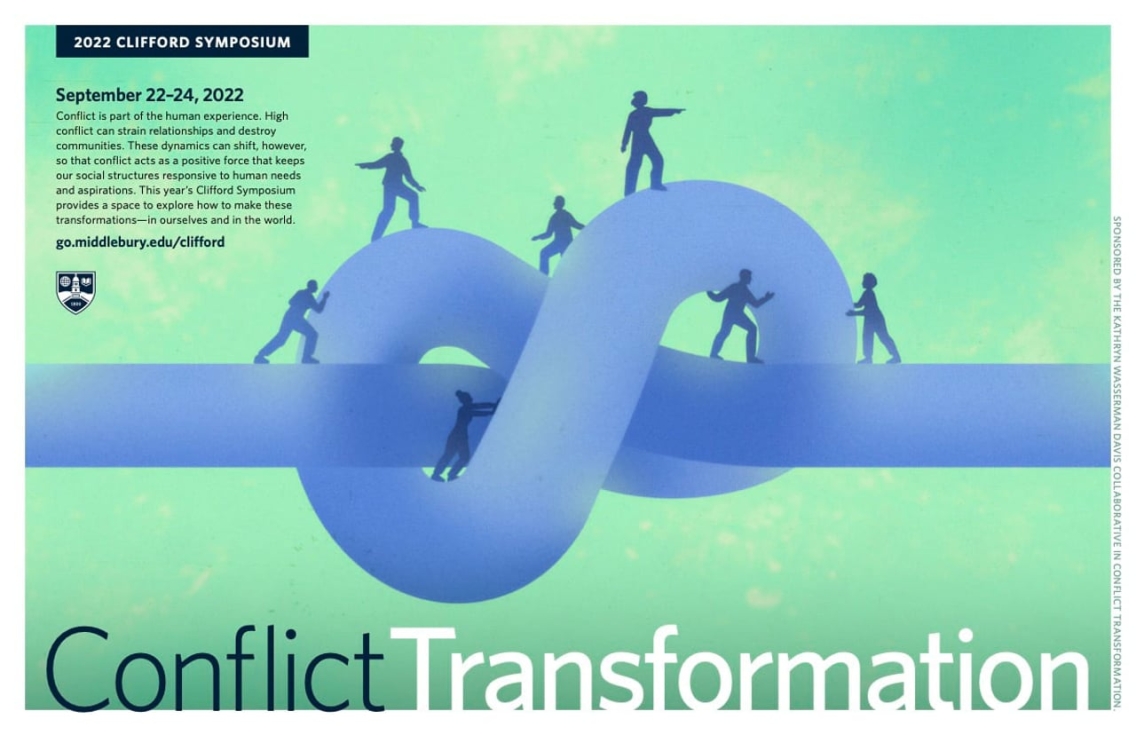

- Thank you. Thank you all for being here tonight. My name is Sarah. I am a professor of political science here at the college and the new director of the Katherine Wasserman Davis Collaborative in Conflict Transformation. I will be brief tonight, but I wanted to begin with one invitation and a few words of gratitude. First, an invitation. The Clifford Symposium is an early conversation about conflict transformation at Middlebury. There will be more. Our team is in listening mode this weekend, so this conversation is for you. We want to hear from you, but we are around, so please reach out with all of it. Your questions, comments, criticisms, thoughts. With that, I will move to gratitude. The work of conflict transformation is grounded in relationships and I am personally grateful for the encouragement, the aid and the support of so many people. The conflict transformation collaborative staff has taken on an enormous load in these first few months. Many thanks to Erin Anderson, our program manager and April Lajeunesse, our program coordinator. I have a lot, so I hope you’ll clap for all of them. The faculty, staff, and students who are supporting the grant and presenting at the Clifford are leading this conversation from within. Thank you for joining them tomorrow and the next day in the Mahaney Art Center on Saturday and in Wilson Hall in McCullough tomorrow. Okay, you can save your applause for all of these thank you to the college staff in communications, facilities, catering, media services, the Knoll, Mahaney Arts Center, Center for Community Engagement Events Management and more. You may not see these people up on the stage this weekend, but this set of events would not be possible without them. Michelle McCauley started off the collaborative and then took up a bigger load this summer as our interim provost, her early plans shaped the wonderful programming that we’re offering this weekend. Our president, Laurie Patton, has made it possible for us to invest deeply in this work. Finally, and I hope you will applaud for yourselves and all of these wonderful people. Most importantly, thanks to you for joining this conversation. You have invested your time. It is time that is the essential and yet seemingly scarce resource that we need to do this work. Thank you for being here and welcome.

- Thank you Sarah, and welcome everyone. It’s so great to see folks here ready to come and talk and listen and engage. Just a reminder about the person that inspired this symposium, the Clifford Symposium was named after professor of History emeritus Nicholas Roland Clifford. Nick Clifford taught at Middlebury from 1966 to 1993 and also served as a trustee, a vice president and a provost at the college. He was well known during his many years on the faculty and in the administration for his ability to cultivate critical inquiry, the kind of inquiry that we’ll be exploring over the next few days. And during this annual event of this symposium, which is in fact the kickoff to the academic year, this year’s theme of conflict transformation is particularly timely. As Sarah just mentioned, we have been the recipient of a grant that has allowed us to create the Catherine Wasserman Davis Collaborative in Conflict Transformation. And it’s an initiative that we intend will embed the principles and practices of conflict transformation in the full continuum of a liberal arts experience from high school through a graduate school with a seven year 25 million grant supporting courses, research and projects across our institution. Middlebury serving as an incubator for the development of a research base, pedagogical tools and student experiences that will reach across multiple states and more than 100 partner universities around the world. And today I am honored to introduce to you one of the central thinkers in this field. John Paul Lederach. John is senior fellow at Humanity United Foundation, which is looking at all of the world’s challenging problems and creating really pragmatic solutions to them. He’s also Professor Emeritus of International Peace Building at the Joan B. Crock Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. And he is perhaps most importantly for all of us today, a practitioner in conciliation processes who is active and has been active on long-term basis in Latin America, Africa and Southeast and Central Asia. John Paul is well known for his work in developing culturally appropriate approaches to conflict transformation and the design and implementation of integrative and strategic approaches to peace building and where he goes peace slash. We served as the director of the Peace Accord Matrix initiative at the Crock Institute and is currently a member of the Advisory Council for the Truth Commission in Columbia. He’s also the author at editor of two dozen books and manuals including Building Peace, sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies, published by the US Institute of Peace Press and Moral Imagination, the Art and Soul of Building Peace published by Oxford University Press. And those students, faculty and staff who are involved in this initiative have all read his little book of conflict transformation, which in its ideas is not so little at all. And I wanted to share with you a few of his words before we hear from him to frame what we are doing here at Middlebury as we continue to explore conflict and its transformation. He writes, “In conflict before we even hear what the other side has said, we assume we know what they mean. We have already attached motives to their messages and even before they have finished are developing our responses. But John Paul argues if we develop our moral imagination intentionally, we will listen differently and be able to make a dent in the systemic forces of oppression and violence that we ourselves are a part of. This capacity of peace building as moral imagination is an instrument more powerful than force and peace building as an endeavor that no longer is a function of outside interventions demanding outcomes foreign to those inside the conflict. Peace building instead becomes a local endeavor, often slow where local actors lead and where we are not cut up in a fascial reflex of “forgiving and forgetting”, but rather remembering and changing. And remembering and changing is a great description of the work of liberal learning.” We are so fortunate to have Jean Paul here with us today speaking to us on conflict transformation, the challenges and promise of this century. Please join me now in welcoming Jean Paul Lederach.

- Thank you Laurie for this welcome and Sarah and others for such a a wonderful day today. In the conversations that we’ve had, it’s the first time that we’ve, my wife and I have visited Vermont and the first time in this famous Middlebury campus. So it’s really an honor and a privilege to be with you for the Clifford Lecture. And I was telling Laurie the other day, that she succeeded where I failed all of you in many regards, some years back attempting to bring the notions of this idea about conflict transformation into the mainstay of the liberal art endeavor. So this this beginning point, this starting point that you’re at is an extraordinary moment. I’m hoping that it ripples into many, many locations. I have, as Laurie stated, come mostly from a practitioner scholar background and this has been a lifetime endeavor starting back in the 1970s until now. I am getting gray hair. I can’t calculate how many decades that is, but it’s a few. And much of that engagement over the years has mostly been in settings of really violent conflict. Journalists sometimes call these war zones local people that I tend to work with I think understand the challenges and the odds that they faced. But they have mostly been my teachers. And I’m always a bit taken aback when people assume that these people who are the teachers are sometimes referred to as the victims because I experienced them as artists, artists of resilience, artists of resistance, artists of social change. So you can imagine that over these years at times my soul has sought to find the ways to sit with suffering and with time my activism as a younger person began to find its way toward more of a contemplative understanding. I go on meditative walks almost every day and I write haiku. Small side note, in fact, my dear wife who’s sitting in the back room here, the back of the room sometimes says that if I had not met her, I might be a monk in the Himalayas. So it gives you some idea. Over these past five years, I have been writing centuries what I call centuries. It’s a kind of a odd style of writing it. It has some roots that trace back to the 14th century mystics from England to the desert fathers and the desert mothers, a way of carrying with them their learning and their understanding in a simplest form that could be remembered at least in my case, this kind of writing falls somewhere between poetry and probes and so it’s mostly unpublishable. It’s not an easy, an easy task to accomplish and to find its way out into the world. It requires kind of letting your hand follow your heart more directly. So not totally circumventing the head, but finding ways that the embodiment of experience moves more directly into the page. It works a lot with paradox. It can move by associations back and forth you hope. Of course for the occasional bit of wisdom, the century name comes from the fact that they were typically numbered one to 100 and that completed a century of ponderings. So I have a book of that’s nearly completed, 10 chapters numbered one to 100, that is 1000 ponderings and I promise not to share them all tonight. But the book starts with something that I learned from a mentor of mine teacher, a Quaker, a pioneer in the peace studies field whose name was, Elise Bolding and she and her husband Kenneth Bolding were two of the founding people who really began a lot of this field here in the US of peace studies. She always taught us through a little exercise how we can locate ourselves in the 200 year present. Now you could take the word present to mean gift and it was a gift what we received from her, but she was referring to a temporal present as in the past, present, and future. And so I wanna start this evening with a little interactive exercise with you because I would like for you to take a moment to locate yourself in your 200 year present. Now I’m gonna follow the basic instructions a bit circumvented because time is short and you can do this in your head if you have a piece of paper, you may want to take a small note or two, but it goes like this. So please join me think for a moment as a starting point of the earliest memory that you have of the oldest person who would’ve held you, tussled your hair, or played with you. So the earliest memory that you have of the oldest person that would’ve held you just get that image of that person. Maybe there’s more than one, pick one. Now if possible, I’ll give an example. Mine would be my great-grandmother, Lydia Miller. My great-grandmother lived to be nearly a hundred years old, ages three, four, and five. During the summer visits I would sit on her lap. Now with the image of that person in your mind, do a rough calculation back to their birth date or better yet to their birth decade, roughly what decade might they have been born in? So I’ll go back to my grandmother, Lydia Miller. She was born in the 1860s. 1860s. Okay, now jot that number down, whatever your decade number is of the earliest memory you have of the oldest person at that time that held you and we’ll segue to the second part. And the second part is to think about your extended family and friendships. Who is the youngest person in your extended family or in your close relationships? The youngest person that you have tussled their hair, played with them or held them on your lap. In our case, it’s our little grandson Issa, who is now three years old right now. Once you have the image of your youngest person in mind, think out ahead and imagine they live a robust life, a robust life. To what decade might they live to enjoy their children, their grandchildren, possibly their great-grandchildren. I think in our case little Issa probably has a very good chance to live past the turn of the century and possibly in past 2110. 2110. And he might be a grandfather by then. So here comes the 200 year present. Take your two numbers, the number of roughly the decade that the oldest person that you knew was born compared with the number of how far out the youngest person of your extended family might live and do this little mathematical equation where you subtract one from the other. So in my case, let’s just take 2110 and 1860. That’s about 250 years, 250 years. Elise would say that is your 200 year present. These are the lives and the people that have touched you and these are the lives and the people that you will touch. It’s an extraordinary thing to imagine our location across centuries. So as a starting point, two thoughts and then I promise to go to conflict transformation thought one, maybe this is the century, maybe this is the century. The century when our ability to imagine our common humanity as a global family will shape whether our species survives. This could be the century of whether our imagination about our humanity as a global family will lead us in the direction of finding the survival of our species. We might call this centuries and centuries forward. Looking back, oh that was the century when humanity found its vocation Thought two, our species vocation and we don’t usually talk about a vocation of a species. I’ve been exploring this question of what is the vocation of a species? Ecosystem Biologist, take note that when a species go missing, all kinds of things start to happen in the ecosystem, which means they have a niche, they have a place, they have a purpose. What is the vocation of the human species? This innate pull to find humanity’s unique niche in our wondrous world where we live. And I do not think that our vocation sits primarily with our capacity to create miraculous cures for the life deadening challenges that we ourselves have wrought. Lemme repeat so that it’s clear. My sense of vocation is not that we invent miraculous cures for what we have wrought our vocation. This is thought two. So thoughts always require counter thoughts. Thought, two, our vocation lies with the imagination we bring for how we stitch repair and weave our way from harm to healing. How we weave our way from harm to healing. In all that has touched us and in all that we touch in our 200 year present, this I think is the century of transformation. We will either get it or we won’t. So hold on to those thoughts. So what’s the seed of this thing? That sounds a bit odd when we use the phrase conflict transformation. You have no idea how odd it sounded when we first started using it with the accreditation boards in Virginia, North Carolina and the southern states that were a part of the association where we first proposed a program in conflict transformation. I imagine here that on occasion people hear it and quirk their head to say, “Hmm, what is this exactly?” It can ring a little odd. So let me start with a story. Where did it happen that for me this became a formative way of understanding my life vocation? I guess you could title this, the story of how a single question gave me everything I needed to ponder for a century of work. I hope in your lifetimes you have a single question at some point in your life that shakes you up enough that you ponder the whole of where you’re going and the purpose that you have. My timeframe was Central America in the 1980s. It was my first deep engagement with peace building in a context that contained at least three civil wars and other countries that had deep social divisions. They were devastating. I was asked by a humanitarian and aid organization whether it might be possible to correspond with and respond to local community leaders who are facing a lot of violence around their question of how do we respond differently and better to these patterns that are tearing us, our communities and our countries apart? I was coming through a program that was focused on social conflict. I have been trained primarily in the skills and approaches of conflict resolution and mediation. So after much consultation, I developed a proposal and met with 30 leaders in Central America from Mexico to Panama, 30 significant social leaders. I vetted my proposal, it was well consulted, it was contextually oriented, it was practically focused and I outlined this around what could happen in a three to five year period. And then we opened up for discussion and that’s when the question came. That’s when the question came. It actually came from a good friend from Honduras. Now let me take a side note for just a moment. Authentic friendships hold honesty and grace together, which is why good friends are usually weird friends because they’re gonna be honest enough to point out things about your quirky life and graceful enough to stay with you. The psalmist once called this kind of friendship, the place where truth and mercy meet the place where truth and mercy meet and went on to say. It also happens to be the place where justice and peace kiss apparently they’re making out. If you can imagine the place where truth, mercy, justice and peace meet, that would be an unusual location in this world. But that’s where the friendship sit. So remember, the friendships that we need for transformative social change are the ones that keep us alive enough to notice what John Lewis, for example, always called good trouble alive enough to notice good trouble connected enough to nurture our courage and vulnerable enough to be reflective, honest and invitational. And I think this is what my friend did. He publicly stood and asked me this question, My friend conflicts we certainly have in this region. I’m just not sure I understand the second part. What do you mean by the word resolution? What do you mean by the word resolution? Because if resolution means that you come down here to solve our problems without changing anything, we’re not interested. We’ve had way too much of that already. There’s a lifetime vocation in those three sentences. Let me just list them out as they hit me in waves for a few years until I had the courage to peer deeper and longer and with a sustained set of conversations with these good and weird friends, the clarity that indeed conflict is with and will stay with us. The simple unveiling that what dominates is a tendency to want to solve problems quickly get rid of them but not really change anything that produces ‘em. The personal journey that he opened up when he said, if you’re coming down here, that’s an onion. I gotta start peeling onions. When you peel, you may notice, have a certain olfactory capacity to spread a room full of smell and often create no small level of tears. Peeling the onion when somebody says who are you? To be able to look at that with honesty was maybe the greatest gift that I received in the early years in Central America. In a word I think he was asking the question, how do we put change at the center? How do we center the changes that we’re after more than the temporary solutions that are often given to us? What is the nature and what is required of us to pursue real and significantly lasting constructive transformation? That’s where it started a shift in my language, my writing and my books that began from that time period forward. It’s always hard to know in a short conversation like tonight’s talk what all to include or not in this wide reaching idea of conflict transformation. In fact, I think Sarah was today asking if all these things are in what’s not in? The big umbrella. And I said, well mostly everything is in because change requires some very significant ways that you hold different streams and understandings. So I thought I would just share a few as a starting point tonight. And the first goes back to that basic notion that conflict is a normal part of human relationships. We were just ordering breakfast the other day. My wife and I and I went up to do the ordering because they had this kind of leftover COVID approach where you would go through a line and they would bring things out, but they weren’t quite full restaurant yet. So I went in and ordered and she likes her eggs a certain way, which where she grew up in in northeastern Indiana, her father always cooked the eggs and he would give them three options. You can have your egg over easy, you could have your egg scrambled or you could have your egg dutched. Dutched, exactly. Big question, right? So I have this in back of my mind that dutch is what she really likes and dutched is when you put your fork in the egg and you fry it. So it’s what some people call over hard and I actually used the word dutched kind of unexpectedly and the person looked at me and said exactly what you said “Dutched?” Well it reminds me of a story that Wendy tells of when she was traveling for the first time in the southern states, I think it might have been Georgia. And they sat to get breakfast and the waitress said, how would you like your egg? And she said, dutched. And the waitress with her southern accent said, “Dutched?”. And Wendy said, “Yeah, you know, without the yolk”. And the waitress looked at her and said, “Honey, any way you fry that egg, you bound to get a yolk. Any way you fry that egg, you bound to get a yolk.” Now that’s conflict in human relationships. Any way you mix the human relationship, you bound to get a little conflict and that is usually not appreciated because conflict kind of messes stuff up for us. What we don’t always notice is what it might offer. And I think it offers a couple of gifts. We don’t always experience it as a gift, but it seems to me that that really is where it’s at because conflict can be the great disruptor of our life, but it can also be the great revelator. It unveils things, it lifts things forward that aren’t fully visible. It functions often as kind of a motor of social change and perhaps least understood conflict offers us a chance to learn to human together better. By the way, spell check has never liked my use of the word human as a verb, so I’m just gonna keep with it. It helps us to learn to human better. This in many ways, sits alongside of the fact that conflict can spiral and it can spiral in nasty and destructive ways. It can move in ways where we lose sight of who we are, where we question everything that’s happening and where it harms our relationships. And there are a lot of dynamics that go with that. But I want to start with the basic point that the question that we face is not whether we’ll have conflict. The question that we face is how and toward what purpose will we mobilize the energy of conflict? And this requires a kind of a mindset shift. A paradigm shift of sorts. And I think the transformational with a transformative understanding often has us looking at a set of deep paradoxes that never really go away. Paradox is the opposite of contradiction, not the pure opposite, but contradiction is one excludes the other paradoxes there’s something of deep truth in both. Yet they are so different that they seem exclusionary. At least three or four of those that I think we face pretty consistently. Conflict will pose the paradox of how we dignify memory while unleashing the creativity of imagination. How do we hold what we’ve experienced with what might be possible, especially when harm has happened? How do we hold nonviolent social civil resistance which escalates conflict in order to lift forward something that is not right with dialogue and engage forms of facilitation and mediation that may be trying to deescalate that which has gone destructively out of hand. How do we hold a place where it’s possible to have both? How do we navigate through the fact that conflict will always be a combination of the personal and the systemic? We are embedded in systems and we are acting as human beings as people who are a part of those. How do we, similar to the psalmist, how do we pursue justice and healing? Those are rarely placed side by side. Those are rarely seen as parts of a bigger equation that’s not fully yet visible. I think my friend in Central America was intuitively on this horizon. He was asking about what image we had of resolution, not that he was opposed to solving a problem but that he had experienced that it takes away the motor of change if it’s dealt with in a way that doesn’t attend to something deeper. And he was begging for something deeper. I think he was right. The transformative lens does not come at this by offering you quick answers. It opens up to discovery and learning. It helps us explore a more holistic understanding of the patterns of harm and the strategies of change and that those have a horizon that we’re aimed for into dignity, repair, healing and flourishing. And in the middle of that, change will always be relationship centric. It will evolve around the quality and the nature of how we organize our relationships, how we experience them, how we respond and nurture them. I often get asked the question, so in this big picture, where do we start? And I do not believe there is only one starting point, but I do think and I lean toward that, a good starting point is some form of proximity. Start with what you have most at hand. What is accessible to you? What comes from the places that you live and the relationships that you have? Because there is a fractal nature to the whole of the equation. Fractal meaning the patterns are similar whether in microcosm or in systemic expression. I sometimes use a small raspberry plant as a way to describe at least two of the significant levels of conflict transformation. Raspberries I used to grow or tried to and discovered, I don’t know if any of you have raspberries here in Vermont. They’re one of those plants that have a mind of their own so to say. You pick place in your garden to plant ‘em and by next spring they’ve arrived in other places where other zucchinis or something were supposed to go and they keep just cropping up because raspberries are one of those plants that have a life above the surface that’s very visible, gives a lot of fruit and a life below the surface that’s very generative. And if you want it, the analogy, it’s very simple, we often pay a lot of attention to what we see above the surface. The times when conflict rises with tension and difficulty, often calling our our attention because it’s creating something that is both painful and difficult below the surface, less visible below that content of what we’re fighting about above the surface is the nature of our relationships, the relational context in which things happen over time and is ongoing. So conflict is often like the raspberry that’s cropping up and you don’t want it there so you may get rid of it only to discovered that you’ve reinforced the dynamics and patterns underneath the ground that will then shoot up these children in other locations. And this is part of the challenge that we’re after in transformation. We include the creativity of a finding good solution to what presents itself as a problem today. But we understand what is being presented as a window and avenue of opportunity into the patterns and the dynamics of the relational context that are ongoing. Maybe take a simple home dorm, vacation home, Challenge that we typically have. Who does the dirty dishes, who left all these dishes in the sink? That’s usually the question that gets asked. I don’t, this is not something that comes from our experience. Of course we have this all sorted out, it’s good transformational people. But I imagine that some of you have faced the question of who exactly is responsible for doing what in household care. It is amazing how dishes can talk. I do not know if you’ve ever noticed this, how something that appears to be fairly straightforward and simple can at a moment’s notice open up into something that goes deeper and further than you could possibly imagine. And when two tired people are back and forthing over who’s doing the dishes or who didn’t do them, sometimes what comes rushing up is the whole of the relationship. And I think that relational context, if you look at it really carefully, tends to pose three questions that get repeated over and again, even if nobody says them. ‘Cause one of the challenges is while we can fight over the content, we have not been so good at finding the vocabulary to locate the deeper dynamics that may be unfolding in our relationships. The three questions are pretty simple. They’re just hard to answer. Who am I? Who are you and who are we? Here’s a simple formula for you to try out. If you fight with the same person three or more times over, basically the same thing. You’re not fighting about the thing, you’re fighting about your relationship, you’re fighting about the nature of who you’re choosing to be with each other and how things are organized. This could be dishes, it could be centuries, could be dishes, could be centuries. Take our country, take a question like belonging, participation, freedom, dignity, say like the way they talked about it in the sixties. I wanna stop a minute and just ask you when I said you know the way they talked about it in the sixties, which century did you locate your sixties in? Was it 1760? Was it 1860? Our civil war? Was it 1960, our civil rights movement or were you thinking out ahead to 2060 and maybe asking the question, is this the century? If we ask? So what is it that sits at the heart of the relational context from a transformative view? I would suggest there are three things that I have almost always found present. Power, identity, and building shared meeting. The first, power. Power has everything to do with the quality of our relationships. Who matters, who is included, who has access, who has influence, who has voice? Who has decision making power? How will the public good and the institutions fulfill their need to serve people and who is served and who is not? Who benefits from the structures, the ways we organize our collective relationships. These questions just keep cropping up at all times in violent conflict, when it goes nasty it often has a deeper resonance around the question of who has been invisibleized, who has not been visible and has had to move to that recourse of last resort? They say that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. What they don’t often say is that powerlessness is a seed bed of violence. The sense that there is no other option. What Bethelheim once commented, As the person who chooses violence, whether against self or other, has no longer seen or imagined the alternative. It’s all that’s left. So it’s one of the biggest challenges is how these things are driven around power and the ways that that is shared. I have never met a relational or social change process that has not traversed the terrains of power and powerlessness, of dignity and humiliation, of exploring the hidden aspects of how much human flourishing ties in with the ways that we organize our interdependence and our mutuality. The second thing always present is identity and identity has a lot to do with how conflict speaks into and back from our sense of place, our sense of belonging, our sense of wellbeing and the experiences on the other side of that, that we are excluded or that we fear or that we see a threat to our very survival. The easiest way to hear identity and conflict is just to listen to the opening of sentences. So if sentences start with you and it’s usually the you with one finger pointed out and three back, well nobody notices the three back you. It’s often coming with accusation and blame and responsibility displaced to the other. That often goes hand in hand with they this generalization about larger groups of people who have created this. The lack of specificity that often comes with that and the circle of kind of us and them-ing that begins to go round and round. These destructive patterns of conflict can be described by the ways in which division defines the boundaries of who’s in and out of the narrowing of groups and of the sense of belonging. They are an interesting and necessary part of finding ways that we associate, but they also can take the patterns of rising polarization until they reach toxic polarization. As conflict intensifies, we tend to have less and less contact with people who disagree with us and we have more and more contact with those who do agree with us. And curiously that contact we have is usually only with people who are like us and already agree with us and we have less capacity to sit with that which is different. We talk a lot about them, we just don’t talk much with them. Here’s another rule of thumb I learned a few years ago. It came out of people that do large scale data visualization and they created these two giant bubbles, red and blue, and they were tracking the blogosphere back in the election of Obama and the blogosphere had them all separated except for a little tiny bit of some ties that went between the two and in the middle of their visualization article, it was based on large scale tracking of how communication flowed in two separate communities. They said this 91 percent of the discourse stayed in the community where it originated. Now one could speculate all interesting things about polarization. I actually kind of took it as a personal question, so lemme pose it to you. Did 91 percent of your communication this week stay only in a community of people that mostly agree with you and that are like you? The third one, creating meaning. Human beings are rather interesting and extraordinary. We have this human interplay of perception and interpretation. It sits in the middle of everything conflict precisely because conflict serves as a disruptor, it often stops us short. We have to look and look again at what exactly is happening and it demands that we look more carefully at ourselves, at others, at what has transpired at what might be coming. But most significantly we find ourselves asking, what does this mean? What is this about? We are so intriguing that we are capable of hearing one spoken word and creating five ways it can be interpreted. That’s our capacity. We hear one spoken word and we create five ways that it can be interpreted. And for good measure we throw in interpretation about the five things that were not said. Even silence speaks when conflict disrupts in conflict. Silence is never the absence of words. Silence is always the presence of something interpretable. These dynamics can be so powerful that it actually has the capacity to change our body functions. I’ll give you at least one example in deep polarization, we start listening with our eyes. I don’t know if you’ve ever noticed this. I more than I care to acknowledge this actually happens to me. Well let’s put it honestly more than I like. We listen with our eyes because we look first to who is saying it and who they’re associated with and then we determine what it means according to who they are, not to the quality or lack of with reference to what they say. Sometimes our feet do the talking. I dunno if you’ve ever noticed this. You’re coming down a hallway, say after a good faculty fight may, maybe it’s a student related thing that took off in the wrong direction and you just noticed at the other end of the hallway somebody who you just disagreed with and you find your feet going “Looney Tunes” exit stage right. And off you go because you’re moving quickly to avoid having to have that human contact with that which creates discomfort In all of this, the court of understanding the transformative approach is how we understand this multifaceted nature of what is happening. So let’s go for a moment to the systemic changes, to the ways that systems evolve. Since the late 1980s, I have been engaged with Columbia. It’s the country where I have had the longest and most significant relationships around the peace building and conflict transformation work. Columbia is a country that has come through 60 years of civil war. If you’re unfamiliar with it, let let that phrase settle in a moment. 60 years of civil war, Most of my work has been with local communities, many of whom have had to face waves and different decades of people that were coming and going with weapons and demanding their allegiances. Close to 5 million people were displaced in Columbia, over these years, it’s a number that defies the imagination in some ways, but now it’s coming out of a half century of war. Six years ago, a peace agreement was fashioned and was embedded into the national ethos and commitments. It’s come through a change of presidential elections. It’s been moving slowly but surely. As part of that agreement, a truth commission was established. I always say that in the National Peace accord, when they established this particular truth commission, it must have been a poet that wrote the title because it’s almost impossible to translate it back from from Spanish to English. So this might be a great location to give it a try with a range of students. My best approach to this in English is the following. The commission is what we refer to in short. This is the commission to shed light on truth, living together and never repeating violence, the commission to shed light on truth, live together and never repeat violence. Now how would you possibly fulfill that mandate coming out of a 60 year war? For the past five years, I’ve accompanied the commission in particular Father Francisco Deru Pacho as we know him, a Jesuit priest who was chosen as the president of the commission. He and I had worked together in a number of regions. He has a deep understanding of various of the worst hit areas in Columbia. And now suddenly he was at a national level leading 12 commissioners and 200 employees in the search for truth across 60 years of war. I want to just take this a little bit so that you can unpack the significance. How do you listen to the suffering of a whole nation? How do you listen to the suffering of a whole nation? This is it, it defies in many regards the the very nature of what we’re accustomed to think about. How do you accomplish that when the war lasted 60 years? How do you, according to their mandate, acknowledge those who in repeated ways experienced deep harms? The plurality of victims in a 60 year war is nearly unfathomable. How does truth contribute to healing these? These are the questions that the commission struggled with just a month ago, couple months ago, they delivered their findings after five years. It would be impossible tonight to summarize their 10,000 pages. Maybe it’s captured in the remarks that Father Francisco Deru gave as he delivered the public delivery of the report to the incoming president. In the course of that delivery, he said these two sentences of the more than 500,000 people killed in the armed conflict, 80 percent were unarmed civilians of the more than 500,000 that were killed in the armed conflict, more than 80 percent were unarmed civilians. And then he said, “If we took one minute to remember each victim, it would take us 17 years. If we took one minute to remember each victim, it would take 17 years.” In the course of accompanying this commission and watching the evolution of choices that they made for how they would address the deep harms that were experienced in their country. I could not help but think of our own country here in the United States. It seems to me that while Columbia is climbing its way out of the hell of civil war, we seem hell bent on climbing into one. It’s often said that the first victim of war is truth. Let me add two other truisms. The first victim of divisive conflict is trust. The first victim of toxic polarization is curiosity. Toxic polarization will kill curiosity, divisive conflict taken deep will kill trust wars, eliminate truth. Truth, trust, and curiosity. If we are to find a way to transform conflict from harm to healing, from toxicity to flourishing, I think these are the three pillars we will need to nurture. So here’s the three lessons that I have taken from Pacho and from the Colombian truth-seeking process. If I’m reflecting on what might be interesting here at home. First their listening shifted. Their listening shifted in the direction of what St. Benedict called, “Listening with the ear of the heart.” Much of the kind of presence they had to create was not about only looking at statistics and reports and data they had that what mattered was the quality of presence they brought to the communities and the families that had suffered. We aren’t accustomed to listening with the ear of the heart, especially when we’re listening to people we may not like. I think it reminds us that that kind of listening is partly what it takes to move from knowing to acknowledging these seem like such connected and simple words. Knowing and acknowledging. But there’s a world of difference. Most of us in the middle of conflict know that harm has been done. People in Columbia know that harm has been done. Why is it so hard for us, whether at an individual or at the level of a whole nation? Why is it so hard to acknowledge the harm? Partly because acknowledgement peels some layers and the biggest layer it appeals is that it unveils, it reveals it. It shows us the things that have been there but not fully understood from the perspective of the lived experience. This is very significant because what acknowledgement does is that it visualizes and validates that the experience of harm that you’ve had is seen. You are seen and it was wrong. Remember that the next time you are in any level of conflict, the difficulty of knowing that those things are there, but the challenge of how they are acknowledged and done so in a way that brings a wider public validation. The second thing this commission did was it worked day and night to reduce the distance between the national and the local. They did this through a number of mechanisms. One certainly was the travel that the 12 commissioners made. The second was the establishment of nearly 30 houses of truth located in the territories as they call them. The locations of the country were the worst of the suffering had happened so that it was proximate and close to the people who had suffered. Reducing the distance is one of the biggest challenges that I think we have. The third element they did, which had never been done by a truth commission, was that they dedicated resources in people to circulate around the world to all the locations where there were exiled and displaced Colombians over the last 60 years. So that the residue of the pain and the suffering that led people to flee, they actually had the commission hold local direct conversations with those 28 countries where exiled communities live. This is a fascinating thing that went hand in hand with open and public interviews of the five presidents who agreed to make what they often called in Spanish, their contribution to truth. For those of you that speak Spanish, contribution to truth, I find it kind of a fascinating thing that truth is not just something you’ll go out there and discover like hanging out somewhere, but you’re gonna need contributions. And that often came hand in hand with people speaking publicly about their responsibilities with communities gathering under the facilitation of the commission to actually meet and talk about where they had harmed each other and how because the commission had this mandate, how you gonna live together? I mean one of the things that happens in a place like Columbia that happens in a place like the United States is that if we look carefully, the conflicts are not half a world away. They’re in our backyards, they’re in our neighborhoods. So part of what was happening was the ability to travel to rather than convene in. To spend time and presence with, to visualize the systemic patterns of what was emergent across those decades of how it could be that across five to seven presidencies the same patterns could repeat. How could it be that even when you had peace agreements that failed the patterns repeated, even this one that we’re talking about today. I think this approach exemplified this commitment to truth, to reestablishing a sense of trust and the ability to sustain a curiosity that was opening and invitational. I think that they in many ways put at the very center a proposal for transformation. Their recommendations by the way, I wouldn’t expect any of you’ll read all 10 of the volumes, but among their recommendations is one that implicates us here in the United States that the war on drugs failed and that new ways of understanding the changes that have to emerge must be acknowledged and invested in that extradition under the war on drugs often removed people who needed to give public testimony to the Colombians but are found in Pueblo, Colorado and outside Sarasota, Florida. In many regards, the commissioners would tell me, we find it strange that people we don’t even know come up and with sometimes tears in their eyes are just telling us, thank you, thank you. And they say, we were so tired we didn’t even know we did anything. I think they embodied hope. I think they embodied hope. Now I cannot tell you how many times my dear friends in the academic world, policymakers and philanthropy that I now work with, how many times I have been told hope is not a strategy, but I have never seen a significant process of transformation without hope. Jorge, the Argentinian poet was one time asked what his view of hope was and he responded, “Ah, hope, ah this hope, this beautiful memory of the future, this beautiful memory of the future.” maybe hope is the muscle that links memory and imagination. Because hope, as I understand it from the communities who continued to seek change was never a thing about waiting for an ideal future to be delivered to them. Hope was them taking a step that embodied the change that they were seeking to build. Hope is the step, not the waiting And maybe we need to exercise this muscle of hope. So let me conclude with a little exercise that I’d like to invite you into to conclude this talk. We started with our 200 year present. I once told a story, it happened to come just after September 11th. I won’t go into the detail because time doesn’t permit, but the story started with this phrase. Everything in this story is true except for the parts that haven’t happened yet. Everything in this story is true except for the parts that haven’t happened yet. So I’d like for you to take a minute and I’d like for you to imagine your 200 year present. I’d like for you to think about that young person. I’d like for you to think about one change, one significant transformation that you would love to see happen in the course of that young person’s lifetime that likely for most of us leads close to the end of this century. One change you hope we can accomplish this century. And when you have time, write the rest of the story. Write it as if you can imagine you telling a great-grandchild how it happened. I think that’s the transformational orientation. It refuses to separate memory from imagination. It understands the difficulty and the complexity. It knows that we traverse a multifaceted ways that change happens, but it comes back, it comes back to us. How are we gonna choose to show up? Thank you.

- We have microphones for questions on both aisles, so maybe we’ll take a round of questions or thoughts and responses and then give our guests a chance to respond and we’ll keep going for a few more minutes.

- [Amy] Hi, thanks very much. I’m Amy Morsman. I teach in the History Department here and I also direct a couple programs at the College and I really appreciated your insights and I kept trying to relate them to my everyday life here and my work and maybe also at home and thinking about conflicts and I loved the verbs that you used human as a verb and then listen and acknowledge, et cetera, et cetera. And I guess I’m wondering if you could speak a little bit more to how important or is it important for both parties or however many parties there are in a conflict to all be understanding conflict transformation? Or does it only require that one party understand what you’re talking about? Thank you.

- [John] Okay. That’s such a good question.

- Just go for it, huh?

- [Audience Member] Would you address that question? Okay. Well it’s, I have rarely had the experience that everybody’s on the same page. Sometimes it happens. But you know, I come from a Mennonite kind of Quaker background if you aren’t familiar with Mennonites. And I learned most of what I needed to know about dealing with Somali warlords in church pacifist conflicts where supposedly we’re all on the same page and we’re all trying to be nice and we end up nice each other to death. So even when we are on the same page, it doesn’t always work in in exactly that way. So I don’t think that it requires that everybody has exactly the same thing. I do think that there are ways in which, because we are, whether it’s even interpersonal or family or something like a faculty or city of Middlebury, as you go on up, every one of those creates a kind of a system and a system of interaction. And often when it’s conflicted, it’s a system of interaction that has a lot of reactivity to it. And the reactivity is not exclusively, but often based on harm that has been experienced or fear. And so the reaction expresses itself quite often in some form of blame or projection or accusation, which is another way of saying I can escape ‘cause if it’s your fault, it’s not mine, I can defend. And that reactivity creates a kind of a cycle back and forth that often makes it difficult to be on the same page. Now having said that, what we know from systems theory and in particular family systems theory ‘cause you were mentioning kind of something a little more proximate and microcosmic in nature, is that as even one or two people within the system define themselves in ways that is proactive and invitational, the system itself has a capacity to rise. This comes from stuff that’s kind of odd in its origins, but it was a lot of family system therapy is based on the idea that you can take out a person from a system who seems to be expressing a lot of the symptoms and work with them individually, but when they’re reintroduced the patterns keep coming. So the questions that I would pose is not so much getting the need for everyone to have exactly the same frame of reference, but the capacity of people to take note of the dynamics in the system and to make intentional choices to be less reactive, more prepositive, more open to hearing, more invitational. There are small things that can sometimes make bigger nudges. Now there are patterns that we are looking at in some of those contexts that date way back around things that may include exclusion and forms of a range of things that might require us to think in much bigger terms. But I think to the kind of question you’re asking, more often than not, the starting point that I’ve experienced is that not everybody’s on the same page. And one of the things you try to work with is clearly that you get people to agree to a kind of a process. If you’re using that dialogical approach, that can be very helpful. But the dynamics even with a good process, are likely to continue. And so the question becomes how do you take note of them and in particular, how do you take note about how you participate in it and what might you do that shifts that a bit? Faculty meetings are a great one. Now as an example, they tend to have the residues of generational conflict, and they kind of cycle back. Yeah, I one time proposed that I thought the whole of the campus could use tea time. I think if there are people that are, you’re having difficulty understanding, perhaps the best thing you could do is go to tea once a week. And that proposes to students as well. You got a four year experience, look out across this campus, find the person who you imagine might be the most different from you find, maybe somebody’s slightly different than you, but reach, you have in your microcosm of these years difference, available, accessible, present. They have a life story. Don’t take it from the angle of something they said in class that you’re rebutting. Take it from the angle that tea coffee once a week offers the opportunity not to agree or solve a problem but offers the opportunity to understand the life story that a person brings. And this is, I think part of what we haven’t fully, fully understood that it’s not just about a technique or arriving at a particular solution or consensus it, it is about how and by what means we rehumanize those things that actually have very subtly slipped into forms of dehumanization and distance.

- Hi, I wish I were a member of this wonderful college, but I’m not. I’m a member of the community and for 25 years I was a mediator for the state of Vermont in special education, did divorce mediation and I taught conflict management and I failed a lot. And what I learned was when I was most successful is when I could love the students and the people I was with and had time to do that. That seemed to bring some progress, not solving problems, but it, it helped a great deal.

- [John] It’s a great observation. I think there was a back here Sarah, there was somebody. Thank you for sharing that.

- Hello, my name is Liam. I’m a first year here at Middlebury College. My question would be in contexts of violence, is transformation always a discussion or at what points does discussion turn to physical violence when there isn’t a clear solution? I guess my question more generally be what is the interplay between physical violence and discussion and conflict?

- Yeah, well.

- Quite so. I don’t know if you’re thinking of a context that might be international in nature or here at home violence is usually the extreme expression of very toxic polarization and often a sense of that are very… that the options have reduced so much that there only are few things that we can do for survival’s sake. Those situations are the ones that I’ve had a lot of opportunity to work with. So similar to what you’ve just heard, I don’t have like fantastic recipes that I’m gonna give you that you will always work. I think what I’ve learned is it takes about as long to get out of a conflict as it took to build it. And so if you’re in a place where it’s been going on for a long time and violence is very prevalent, I think it’d be wise to think in decades if not generations. The second is that many places have combinations of structural and open violence, structural being forms of exclusion, less access, things that are less visible, and direct violence being weapons and the whole kit and caboodle. These are places that I think require a real commitment to understanding the significance of what it means to be born into repeated cycles of this. And how trauma is not just captured by the understanding of a post traumatic event, but that trauma is carried in the body and can be transferred generationally. And so this again, kind of pushes us in the direction that much of what we need to do is to create the spaces for people to feel that they are attended to, even when they express some of the worst behaviors are attended to for the purpose of understanding more deeply where they have come from, what their life is about and where they’re hoping to get. And that it’s kind of a form of bearing witness more than a form of taking in solutions. So I think my friend in Honduras, just to give you an example, what he was saying, you’re coming down here is, as they say in Spanish, you do gooders that are arriving with the answers. We don’t need that. We need people that are gonna be alongside of us. So in those settings of violence, I have a somewhat different approach than some of my colleagues in the international world of mediation in that most of my explorations have been in the direction that even in the situations that appear to have fewer, no resources are often places that are filled with people who do have ideas and resources and relationships. So I’ve worked mostly with an approach that if the technical term was used, we might say, rather than an outside neutral that kind of moves between and tries to get people to reach a ceasefire, are approaches that are working with people who are embedded in the conflict, but whose relationship keeps them proximate and close to one or another side, but who have an ability to bridge and where a few of the inside partial rather than outside neutral, where even a small number of them have a capacity to coordinate and circulate. Something happens within that resourcing that has a deeper connection to the context, a better understanding of the meaning that people are giving to things and an ability to hold the conversation over the periods of time that will often be needed. My Central American experience was initially of that model, of that approach between the indigenous armed groups in the Sandinistas government in the 1980s. The people who were involved in that early conciliation were not outsiders. They were people who were mosquito and from Managua, from the capital city. But who had the trust of each side, but who was a team created a repository of a circulating trust. The same exact thing we found to be true in the prisons in Northern Ireland. So working across loyalists and Republican para militaries, the day that they began to catch an imagination that given the long history of what they had participated in could be transformed in the direction of them contributing to ending the violence, which for most of their views was something they did not want to transfer to their grandchildren. So that’s the starting point. Quite often it’s this notion that you understand that the wellbeing of your grandchildren is actually tied to the wellbeing of your enemy’s grandchildren. When that started to happen, there was something that created, I think the social tissue that helped the Good Friday agreement stick, even though they were not primary negotiators and they were much more proximate to the street violence. So their capacity to know what was happening and to move in a way that could both coordinate and alert and to move back in a way when it was too dangerous was extraordinary. I’ll go on to one more. It’s the same exact thing that I’m finding with the engagements that we have here in the US where to take Anacostia outside of Washington DC they have sets of what they refer to as credible messengers. Credible messengers are people who are mostly people who have returned from prison and who at an earlier stage, were a part of very significant levels of some form of violence. Now in the place that they are in life, they’re opening up mentoring relationships on the street level. And they’re credible messengers because the younger kids carrying today know who they are. I could not do that work. That’s not the kind of thing that I can do. Now, what I, what what can be possible is I can give, I can give encouragement, accompaniment support. I can be a sounding board, but it’s people who have captured that imagination are often the ones that are most proximate to the situation and are able to mobilize the resources that are most needed for the hardest of the situations. And yeah, so it’s not easy. Violence is so much harder to back down and away from what happens with violence. And so this whole notion of finding ways to prevent it before it gets there is really key, which is a lot of what the credible messengers work with. They pick up what’s happening where they try to move quickly in a way that alleviates the need to create the next cycle of some form of back and forth, either revenge or killings or drug related stuff that sometimes happens. So context matters. And I think it’s the power in many ways of culture that we misunderstand from the outside because we only see it as something that’s bereft of everything that should be good. The opposite in my experience, is true. There’s extraordinary resource and most often in great proximity to places that are the hardest hit.

- [Moderator] I think we have time for one more question.

- David Stoll anthropology, judging from some of the examples you’ve just mentioned, which would include I think violence interrupters in Anacostia peace negotiations in Northern Ireland, Columbia, would you accept that what you’re doing is trying to build up a peace party of people may have been on one side or the other, but now they realize they’ve lost a lot more than they’ve gained? Their mother’s surviving brothers, some of them did buy into one side or the other, but it’s a burned over district. Columbia after 60 years definitely a burned over country. And so in effect, you are looking for people who are willing to talk to each other, which sounds great to me. That’s wonderful. But if that’s what you’re doing, then there’s a separate problem of who you can’t really talk to because they have benefited so enormously from the status quo and to deal with them, I’m not sure, well, would you accept that basically to deal with the capos, the Vladimir Putins, the Mexican cartel leaders, who are now making extortion a way of life. They apparently get more of their money from extorting their fellow Mexicans than they do from selling us drugs. Basically, you still need some combination of police in even military, military domination in some of these cases, and then in other cases, really tough policing. Would you accept that? Obviously quick and nasty summation of what you might or might not be trying to say.

- Yeah. Well the answer is from a practitioner scholar, where the realities of a situation create the contours of who you need to deal with. But this is also a practitioner scholar who’s one change this century is that we move away from the production of weapons, is the way we handle our differences. So yes and no. There are realities that you have to deal with and you don’t walk away from ‘em. But on the other hand, even the Putin’s right now of the world, this rise of authoritarianism, there’s a lot of things that facilitate that. It’s not exclusively that they’re somehow just bad people. And there’s a lot of ways in which have we, if we can develop… So to take your question, yes, I am trying to create a peace constituency. One that believes that humanity has the capacity to understand ourselves as a global family, and one that believes that it’s possible that we can reach the evolution of the aspirations of most of our deepest value structures, which are those that we respect dignity, and we encourage words over weapons, but our investments are not going those directions. And there is a lot of people at benefit. So one of the big challenges is the fact that Mexican cartel, where do most of those guns come from? It’s not just Mexico. It’s a extraordinary stream of flow of weapons that is in this world. There’s a lot of money in it. The Columbian peace accord posited the shift in production of cocaine. And you have to imagine the challenge of establishing a capacity to shift small production farmers from coca into something different when you’re looking at a chain of value that runs globally. And so I what I want to try to express as clearly as I can, I do not negate the complexity of the challenges that lie before us, but I believe that we are capable of finding ways to do it differently. And little by little, I think those are the steps we take. So yeah, I’m a pacifist who’s spent most of his time sitting around table with people that carry guns going through their neighborhoods. And the thing that I found is basically this, we’re not called upon to judge the choices that other people make in that kind of a situation. I think our challenge is how do we imagine alternatives that they can find acceptable to move away from it? And that’s where my invitation is. I’m looking for a lot more people to help sort that out. And it’s gonna take every single discipline and student that we can possibly think of to move in that direction that may be unsatisfactory. But welcome to my life.

- [Moderator] Thank you all for being here. For tomorrow’s events and Saturday’s events, please check out go/Clifford for the schedule. Hope to see you soon.