Queering the Archival Process: a Case Study from the Eugene Exman papers

“Archivists are trained to resist contextualizing historical artifacts in an effort to maintain ‘neutrality.’ However, it is naive to think that processing a collection will remain an objective process. This is precisely why it is important to forgo this presumption and affirm the significance of contextualizing materials so as to not foreclose any interpretations.” (Lizeth Zepeda, “Queering the Archive: Transforming the Archival Process,” 96)

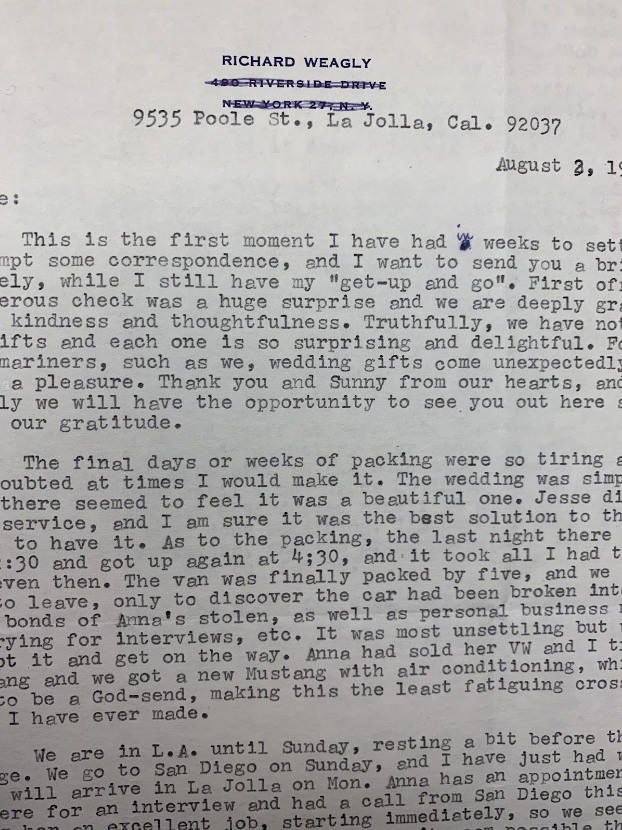

In early June 1965, Eugene Exman received a letter from W. Richard Weagly, the choir director at Riverside Church, where Exman and his wife Sunny were active in the congregation. The letter begins, “Dear Gene: Since yesterday, I have been thinking much about one of your statements: ‘I believe that I could bring Virgil back to you, but I feel he must make the decision in his own mind and heart.’” A few paragraphs into the body of the letter, Weagly continues,

As for myself, you asked me: ‘What will you do?’ I do not know! I have tried to say to myself, Virgil is dead, but this is a vain effort. With death there is regret and sorrow but peace eventually comes. I have no peace anywhere. When I am alone my mind is filled with Virgil and all the happy past; when I am with others I am a misery to them with my moaning….

As you told me yesterday, Virgil has also let me know that I am in his will. To me, this is an illustration of the entire matter. I could not balance my love for him with money or an inheritance due to death. I don’t want any of his estate and hope he will awake to the falseness of his gesture, and perhaps you will tell him to remove me from this will. I invested my life in his life for 34 years and the return in interest was generally of a very high calibre. That life is no longer wanted, nor can the remainder be invested in any other way, so what do I do with it? I gave all I had and it wasn’t enough.

The letter is just one example in the collection of Exman’s advising role among his friends and colleagues, but it can also serve as an exercise in what archivist Lizeth Zepeda describes in “Queering the Archive: Transforming the Archival Process” as “contextual research” in “places that could be read as queer” (95). The Virgil that Weagly refers to in this letter is organist Virgil Fox, who had just resigned from Riverside Church and ended his personal and professional relationships with Weagly after several years of repeated fallings-out. Fox and Weagly had been hired as “a partnership,” according to Riverside’s monthly publication, in 1946, at which point the pair had already been living, working, and vacationing together for over a decade. In his other letters to Exman, Weagly occasionally refers to his relationship with Fox as a “friendship” and an “association.” Usually, he doesn’t define their relationship at all, instead alluding to arguments, events, and dynamics that Exman was presumably already familiar with. Weagly’s misery at the loss of his relationship with Virgil is palpable in the following letters, which document his “sabbatical” from Riverside, during which the church Board and officials including Pastor Jim McCracken arranged for Weagly to receive psychiatric treatment from Dr. William Sargant and Dr. Albert Mason in England. Weagly eventually resigned as choir director at Exman’s urging, due to an increasing likelihood that the church Board, looking for stability, would dismiss him otherwise (Eugene Exman to W Richard Weagly, April 19, 1967).

During his time away from Riverside, Weagly concluded a Christmas letter to Exman with a paragraph about a mutual friend, Anna Brandt: “Anna is the nearest and dearest thing I have, but I still can not see my way to follow your suggestion, and she is willing to sacrifice herself for me, for what companionship I can offer. So– my selfishness or doubt or hope still rules the roost.” (W Richard Weagly to Eugene Exman, December 25, 1966). Exman’s suggestion seems to be related to Weagly and Brandt marrying: when Weagly eventually wrote to Exman in 1968 to invite him to their “extremely simple” wedding, he noted that “I had not thought the matter through carefully, as there are so many things that are new and different about all of this… I would not want to feel that I have posed a problem or burden for you, but if there is a desire on your part to be in at the next chapter, one which you have envisioned and favored for a long time, both of us would be more than grateful.” (June 6, 1968).

The following summer: “On July 7 we will have completed at least our first year of marriage successfully, and with a high degree of contentment and happiness. I never could have believed it!” (June 15, 1969). A year after that, on June 17, 1970: “We have a beautiful home, and I am happy in the marriage, despite the memories of another thirty-four years. Anna is another gift of God, and, like everything else in my life, more than I deserve.” The last letter from Weagly in the Exman papers is dated March 24, 1975, seven months before Exman’s death, and contains a P.S.: “Not having heard from Doktor Fox in seven years, I phoned him Christmas Eve, and after many delays and much shuttling from person to person, I finally made it…… only to learn he couldn’t recognize my voice. HA!”

The traditional approach to describing these materials would not include making space for a queer interpretation of Weagly’s experiences, as Weagly does not self-identify as gay, bisexual, or queer or explicitly describe his relationship with Virgil Fox as romantic or sexual. Instead, an archivist might only state confirmable facts like names, dates, and locations in order to maintain as much “neutrality” as possible. A traditional description for this unit of correspondence between Exman and Weagly, therefore, might look something like this:

This folder contains correspondence between Eugene Exman and W. Richard Weagly dated between 1955 and 1975, regarding Weagly’s departure from his position as choir director at Riverside Church, as well as his medical treatment in England, relocation to California, and marriage to Anna Brandt.

However, according to Zepeda’s definition of queering the archive, insisting on a “neutral” interpretation of these materials by leaving the implications of Weagly’s and Fox’s “association” unacknowledged would be a disservice to users, as it would keep them from accessing the whole story. Handling these records through what Zepeda calls a queer lens would require acknowledgement of the places in these records that deal with emotion, implication, and circumstances – that is, not only what Weagly did, where he went, and who he interacted with, but also under what circumstances he did so, how he felt about it, and how these factors might make space for interpretations that contradict the dominant, heteronormative perspective. Drawing these elements into an archival description of these materials might result in a description that looks like this:

This folder contains correspondence between Eugene Exman and W. Richard Weagly dated between 1955 and 1975. It includes many letters regarding the end of Weagly’s personal and professional relationships with organist Virgil Fox, with whom he had lived and worked since the early 1930s. These letters also refer to Weagly’s subsequent psychiatric treatment under English psychiatrists William Sargant and Albert Mason, as well as Weagly’s resignation under pressure from Riverside Church officials from his position as choir director. Later letters refer to Weagly’s relocation to California and his marriage at Exman’s suggestion to his and Exman’s mutual friend Anna Brandt.

See Weagly’s folder in the Eugene Exman papers finding aid, with descriptive note: Weagly, W. Richard “Dick”, 1949 - 1975 | ArchivesSpace Public Interface (middlebury.edu)

Unlike the first example, this note contains context that makes space for a queer reading of these materials in the following places: firstly, it directly acknowledges the intimacy and importance of Weagly’s and Fox’s relationship, even though it does not attempt to define this relationship or the two men’s orientations or identities. Secondly, it specifies that the treatment that Weagly was sent to in England was psychiatric in nature during a time when homosexuality was heavily pathologized, and it provides further access points in the names of his doctors. Notably, William Sargant was known for his controversial practices, including multiple practices historically used to “treat” homosexuality, such as electroshock therapy. Thirdly, it notes that Weagly’s resignation from Riverside Church was under pressure from church officials related to the events following Virgil Fox’s departure as organist, rather than being an unrelated decision on Weagly’s part. Finally, it notes that Weagly’s marriage to Anna Brandt did not follow an assumed, heteronormative trajectory (they met, they fell in love, they married) but rather resulted from the combination of Brandt’s and Weagly’s long-term friendship as well as repeated external suggestions from a close friend and advisor. While none of these contextual elements assume Weagly’s identity, they all work to disrupt the heteronormative assumptions allowed by a more traditional, “neutral” description of these materials by bringing the user’s attention to the tonal, emotional, and cultural information “between the lines” of these letters.

In “Queering the Archive,” Lizeth Zepeda describes her experience processing the Sarah S. Valencia collection at the Arizona Historical Society using a queer of color lens, using contextual information about Valencia’s life, family, identity as a woman of color, and religious experiences to make space for a queer interpretation of the materials from Valencia’s archive. Zepeda notes that she “did not label the manuscript collection as gay, lesbian, or queer,” but that she “considered other possibilities like adding context to the significance of those photos and Valencia’s life in the historical or biographical note of the finding aid.” She also decided to revisit this collection and request to add context to the control file and to add ‘cross-dressing’ as a Library of Congress Subject Heading in the catalog record (Zepeda 98). It should be noted that my experience of processing these materials differed from Zepeda’s experience processing the Valencia papers due to the fact that the creators of the records in the Exman-Weagly correspondence were white men and, therefore, a queer of color lens was not completely applicable. However, I was able to draw from her process of “queering” in my own professional process with the Exman-Weagly correspondence. Like Zepeda, I recognize that ascribing identity terms to this portion of the Eugene Exman papers as subject headings may not be accurate or assist users with access. However, I plan to incorporate the above note based on Zepeda’s queer lens into the description of these materials in order to ensure that users interested in 20th-century queer history in the United States, particularly with regard to interdenominational communities such as Riverside Church, are able to find and use these records for their own research.

Works Cited

Kaskell, Lilo. “Virgil Fox and W. Richard Weagly at the New Organ Console in the Nave, 1948.” The Riverside Church, riverside.whirlihost.com/Detail/objects/11996. Accessed 20 Mar. 2024.

Torrence, Richard, and Marshall Yaeger. Virgil Fox (The Dish): an Irreverent Biography of the Great American Organist. Circles International, 2001.

Zepeda, Lizeth. “Queering the Archive: Transforming the Archival Process.” DisClosure: A Journal of Social Theory, vol. 27, Jan. 2018, pp. 94–102. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.13023/disclosure.27.14.

Anna Hurd is a second-year Masters of Library and Information Science/Archives Management student at Simmons University. She will be working to process the Eugene Exman papers at Middlebury through November 2024. Stay tuned for updates, behind-the-scenes glances into the processing process, and details from this enigmatic collection.

Anna self-identifies as queer and uses both she/her and they/them pronouns. Some resources about describing LGBTQIA+ identities and stories in archival materials are listed below:

Homosaurus: an international LGBTQ+ linked data vocabulary

Resources about controlled vocabularies and classification schemes, compiled by ALA Rainbow Round Table