Two is Company, Three’s a Crowd: A Brief Bibliographic Study of Middlebury College’s "The New Testament, The Booke of Common Prayer, and The Whole Book of Psalms"

This past J-Term, I had the pleasure of taking Dana Hart’s HARC1060: Print Culture and the History of the Book. The class was embedded in Special Collections, so we had readings, lectures, and discussions on old books, and then we got to come into the reading room and see and touch the old books!

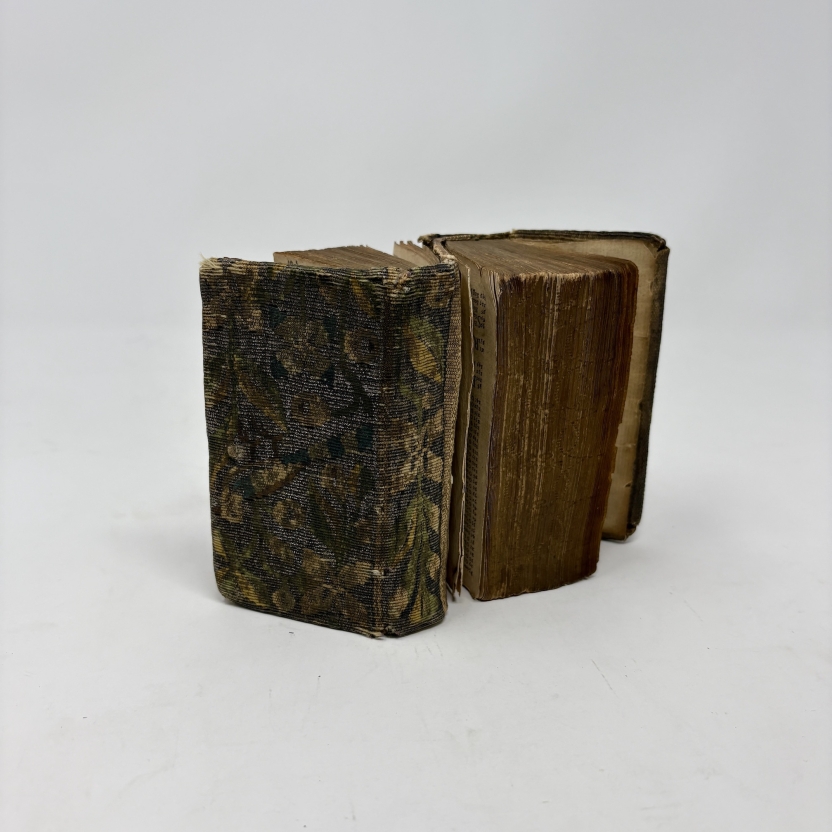

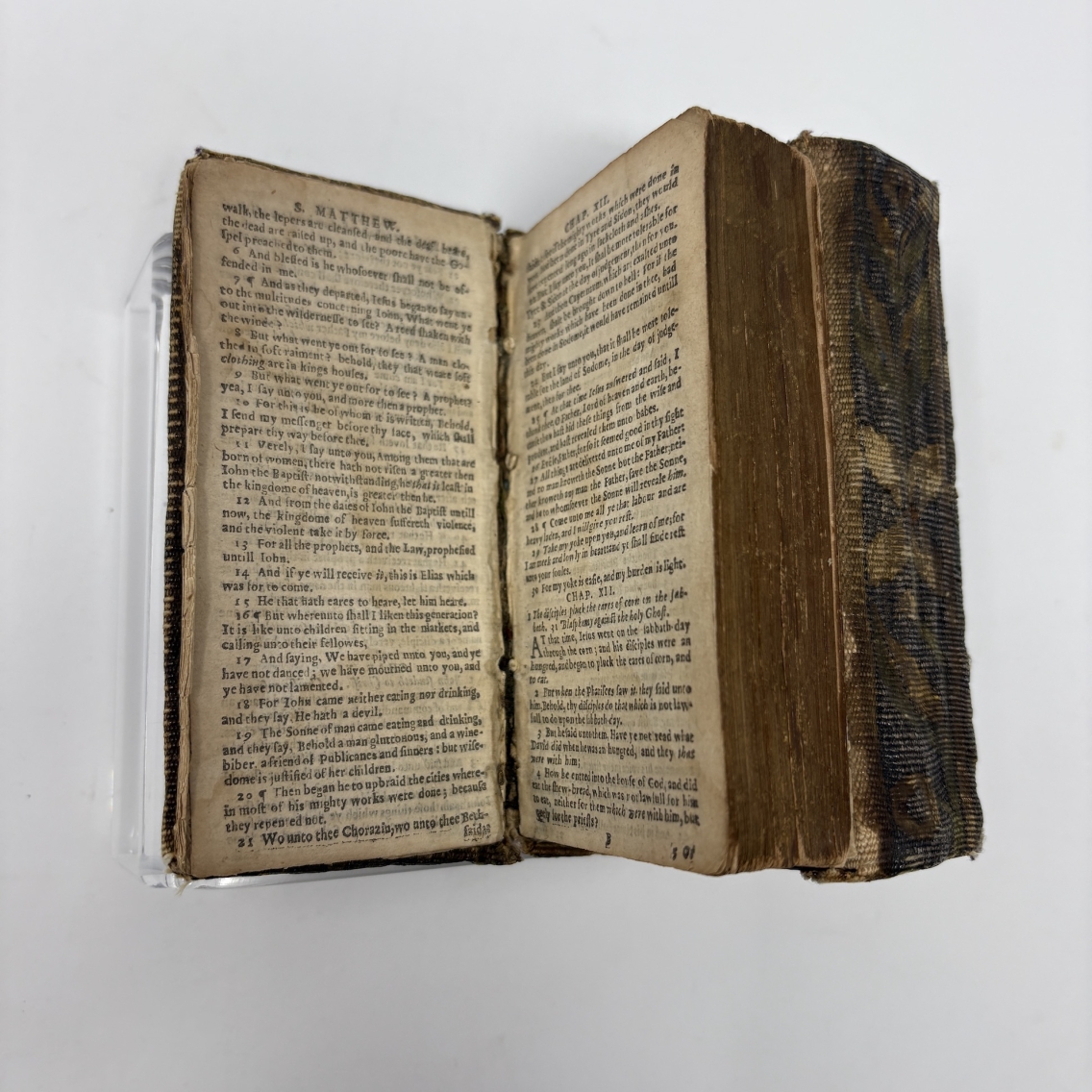

Our final project was a paper and presentation on a book printed between 1450 and 1800, and held in Special Collections. I selected a small book that actually contained three books: The New Testament and The Whole Booke of Psalmes (both printed by Cambridge University Press in 1628), and The Booke of Common Prayer(printed by the King’s Printing House in 1629).

This book is bound in a dos-á-dos binding (the books share three boards and two spines in a binding that zig-zags through the middle) and features an embroidered cover and binding and gilt and gauffered edges. The artistic and structural choices build off each other and make sense within the culture that produced them. These particular texts were bound together so they could be used together. For a large text block (1,224 pages!) a dos-á-dos binding maximizes the amount of content in one book, as the double binding configuration provides more support and structural integrity. In the seventeenth century, embroidered bindings were often paired with dos-á-dos bindings, and embroidered bindings typically received gilt and gauffered edges. Gilt, typically done in gold, makes the edges of the pages smooth and shiny and serves a functional purpose as well: protection from dust. Gauffered decorations were added on top of the gilded edges with heated rolling tools which indented small repeating patterns. Each aspect enhances the book’s durability and visual appeal.

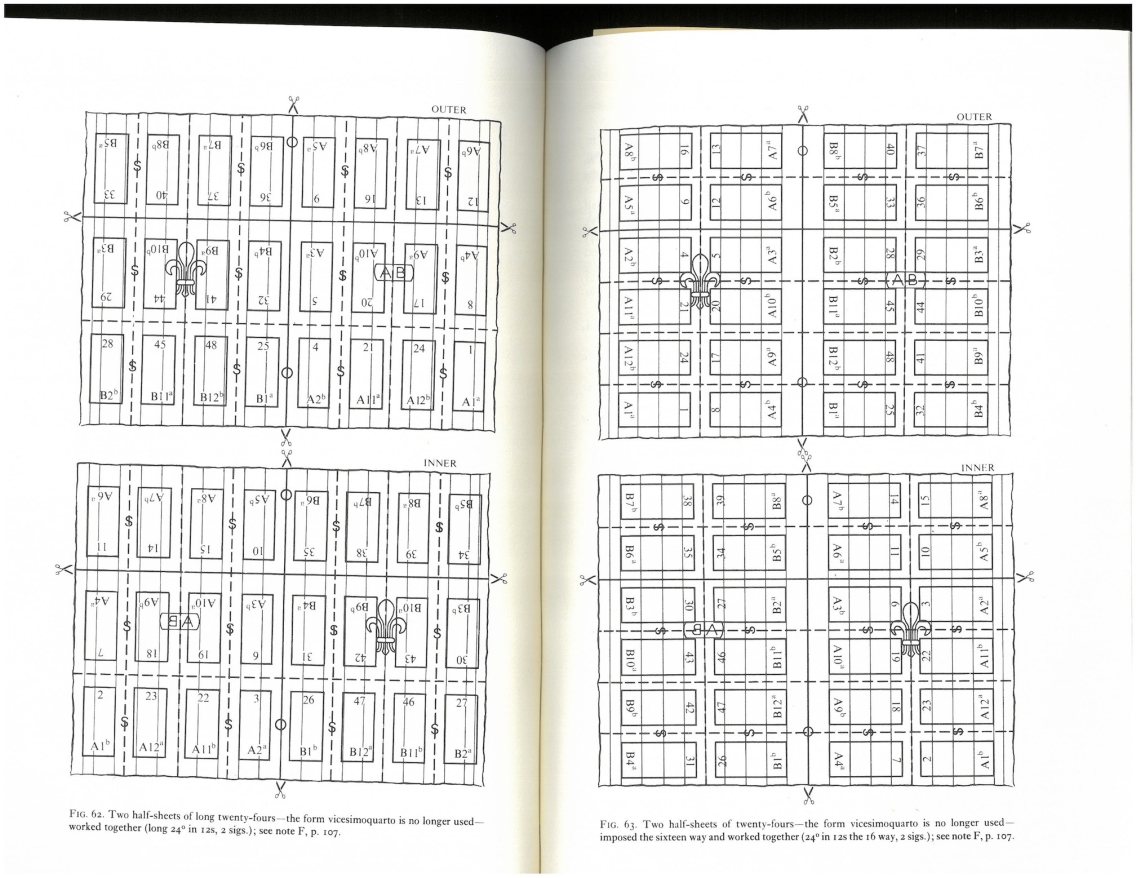

This book’s format is a “long vicesimo-quarto,” meaning one sheet of paper was cut and folded to create twelve leaves (twenty-four pages) per gathering. The following image is from Philip Gaskell’s A New Introduction to Bibliography and shows how a single sheet of paper would be cut, folded, and imposed to create a vicesimo-quarto book.

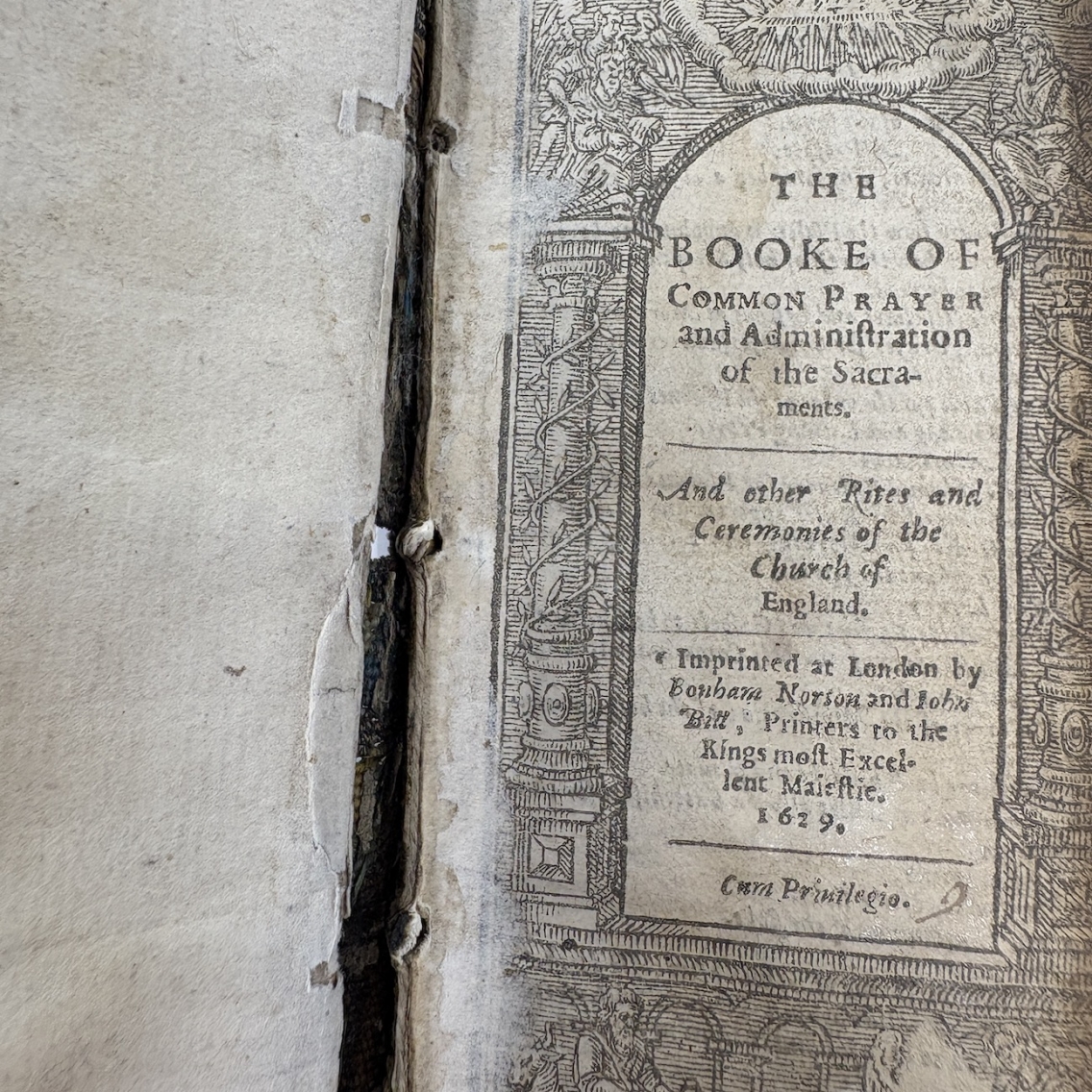

Beyond structural components, this book has a fascinating printing history! I began to look into the history of the King’s Printing House (KPH; printers of The Booke of Common Prayer), and realized it was an incredibly complicated story (re: lawsuits, transferring assets and debts, strategic marriages, etc). The KPH had the (nearly) exclusive right to print the Bible and The Book of Common Prayer, and King James IV assigned Robert Barker as the King’s Printer and John Norton as the King’s Printer in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin in 1603. Barker and Norton set up a three-way partnership with fellow printer John Bill to print and deal books. In 1611, Robert Barker headed the task of printing King James’ Bible, which put him in significant debt. In 1615, Robert Barker, Bonham Norton (cousin of John Norton), and John Bill entered into the “1615 Assignment,” and Norton and Bill agreed to settle Barker’s debts in return for land, estates, and a strategic marriage between Sarah Norton (Bonham Norton’s daughter) and Christopher Barker (Robert Barker’s eldest son). Bonham Norton and John Bill bought into a three-way partnership with Christopher Barker. Within this partnership, many court battles, transferring assets, debts, and titles ensued. In 1620, Bonham Norton was reinstated as King’s Printer alongside John Bill, and in 1629 they printed the The Booke of Common Prayer included in the book I focused on. In October of the same year, the court ordered that Robert Barker was to replace Bonham Norton as the King’s Printer (joint with John Bill) and Bonham Norton was imprisoned (where he stayed until his death in 1635). John Bill died in 1630, leaving the King’s Printing House duties to Robert Barker, who was sent to prison for debt in 1635. However, Barker continued his duties from prison, and books printed by the KPH continue to list Robert Barker as the King’s Printer, assigned by John Bill.

Printing in seventeenth century London was not a stable or secure job, even for the highest of them all. This complicated and dramatic history is so interesting to me, and not something that I ever would have guessed when I first opened up my book and saw John Bill and Bonham Norton listed as the printers.

If you are interested to read my way-more-in-depth final paper, it can be found here: two is company. To book an appointment to see this book (or many other fabulous incunable books) in person, visit go.middlebury.edu/specialvisit. And, follow us on Instagram @middleburyspecialcollections!

References:

Baillie, William M. “Bibliographical Notes: Early Printed Books in Small Formats.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 69, no. 2 (1975): 197–275.

Davenport, Cyril. English Embroidered Bookbindings. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company, 1899. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/17585/pg17585-images.html #plate_10.

Gaskell, Philip. A New Introduction to Bibliography: The Classic Manual of Bibliography. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 1995.

Queen Mary University of London, Department of English. “Time-Line of English Printing under the King’s Printer (1506–1640).” http://www.english.qmul.ac.uk/kingsprinter/ publications/transcripts/Reader_Aids/TIME-LINE.pdf.

Wakely, Maria. “Printing and Double-Dealing in Jacobean England: Robert Barker, John Bill, and Bonham Norton.” The Library 8, no. 2 (June 2007): 119-153, https://doi.org/10.1093 /library/8.2.119.

Liefe Temple is a joint English and Dance major from the class of 2025.5, and a Student Associate at Special Collections. Her passion for librarianship extends to her current work as note-taker for the Ilsley Public Library Board of Trustees and previous summer work including with the Bixby Memorial Free Library in Vergennes, Vermont.