Student Research Spotlight: Sea Minks of Maine

Olivia Olson’s research on the extinct sea mink could help inform conservation strategies for the American mink and other furbearing animals in the Northeast. Her summer examining bones and teeth was funded by a Janet C. Curry Research Fellowship, and her findings will support her ongoing senior thesis.

My name is Olivia Olson and I’m from Islesboro, Maine. I am a senior studying ecology and evolution in the biology department in the HEDGE (Holocene Ecology, Diversity, and Global Extinctions) lab under the guidance of Alexis Mychajliw, associate professor of biology and environmental studies.

The work I did this summer will provide the basis of the data I use in my senior thesis: Investigating the Ecology of the Sea Mink (Neovison macrodon) in the Shell Middens of the Maine Coast. Shell middens are indigenous cultural spaces. They were used by indigenous communities to hold shell and bone refuse, artifacts, and remnants from burials. Some of these amalgamations date back 5,000 years and were used through contact with European settler-colonists.

![Olivia Olson and [GET NAME] hunt for shells on the beach.](/sites/default/files/styles/1136x639/public/2021-09/Screen%20Shot%202021-09-22%20at%202.58.09%20PM.jpg?fv=KmV9Gn8g&itok=Z0_AvEqM)

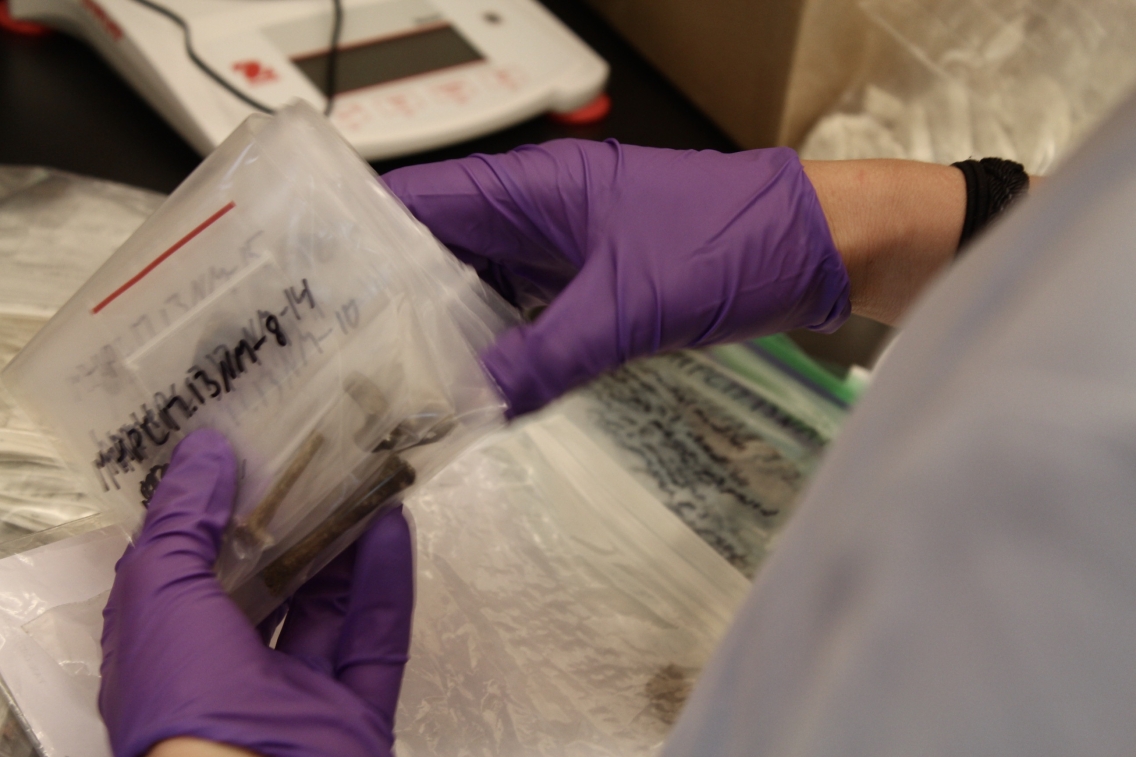

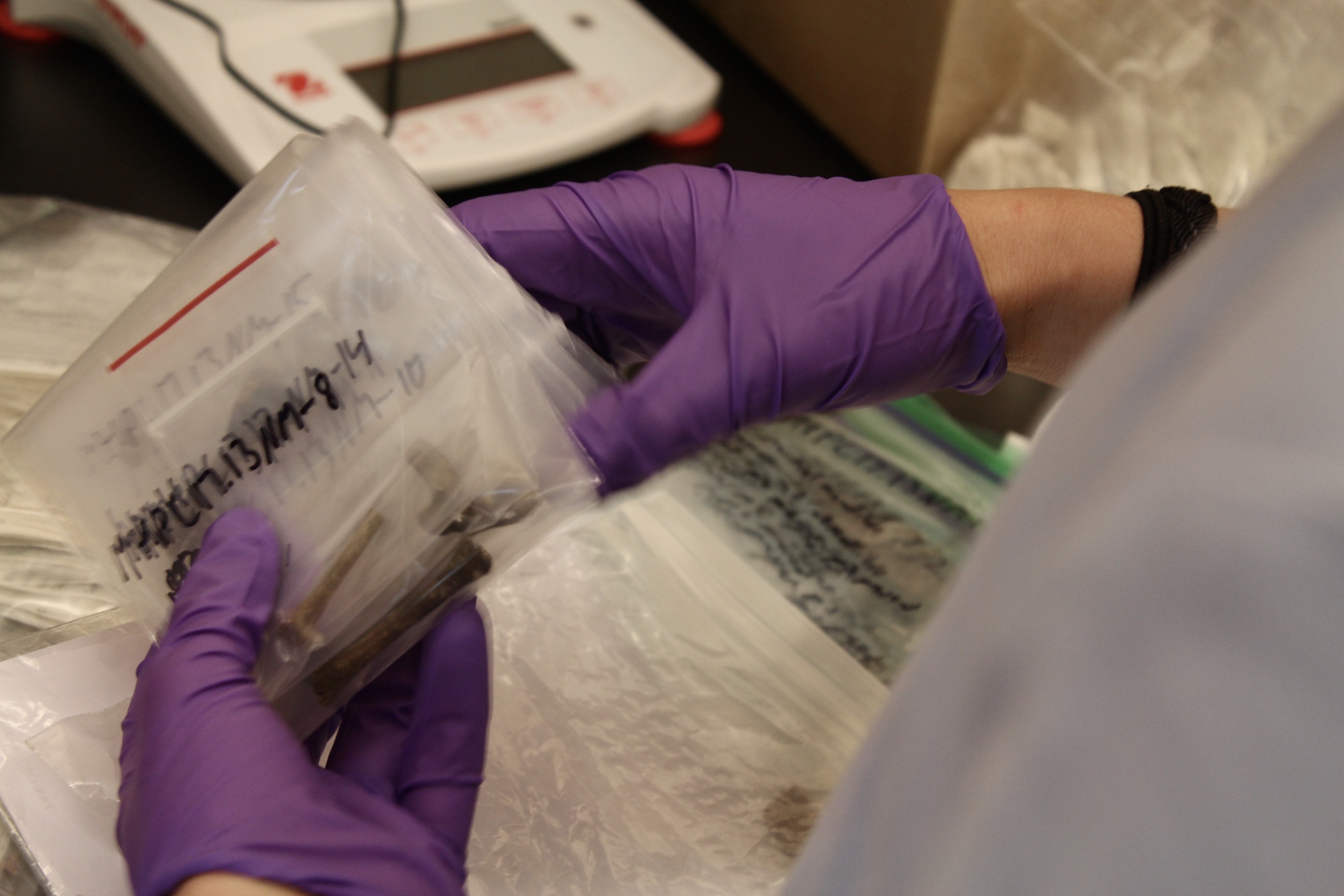

This summer, I cataloged over 925 elements of bone and teeth from three different shell middens along the Maine coast and measured 192 elements from those samples. These samples are on loan from the Maine Historic Preservation Commission and the University of Maine. Part of my summer work was to connect with and support our collaborators in Maine. They were generous with their loan and time spent answering my questions. At the end of the summer, I compiled the data and sent them a summarizing document outlining my summer work and what I plan to do in the future using the samples they lent the HEDGE lab.

I am interested in comparing the ecomorphology of the sea mink to its extant sister taxon, the American mink (Neovison vison). By using the information I’ve gathered on the size and shape of its bones and teeth, we can learn how the extinct sea mink moved, hunted, and ate. Additionally, this fall, I will be conducting biochemical analyses to date the bones and teeth and to find out what they ate. This research will indicate how differently sea mink and American mink may have used their environments and how humans may have interacted with them. This work can inform conservation strategies, and will hopefully contribute to the management and care of American mink and other furbearers in the Northeastern United States.

In addition to the lab work I conducted this summer, I also wrote several blogs for the HEDGE lab. In them, I described the fieldwork I participated in in June. Professor Mychajliw, her collaborator from the University of Oklahoma, and I visited several shell middens and spoke with local naturalists, hunters, trappers, and academics along the way. I also wrote about the lab work I was engaged in. These blogs publicize the lab and the work we are doing. The pieces have added to my portfolio of published science communication and have allowed me to practice my writing skills.

Read Olivia’s blog posts from “Ecology and Evolution”: