Seminars 2022-2023

’Toxicity‘ Seminar Participants

James Calvin Davis

George Adams Ellis Prof of Liberal Arts; Professor of Religion

Seminar Leader

Moral Imagination and the Liberal Arts

This project considers imagination as an ethical concept, a social virtue, and an essential “learning objective” of the liberal arts. As a virtue, moral imagination is the intellectual capacity that allows us to see (albeit imperfectly) from perspectives not our own, to understand convictions we ourselves do not prioritize, and to appreciate experiences we have not had. Moral imagination enables us to critically reshape our understanding of history, while envisioning futures that differ substantially from the present or past. By contrast, the failures of virtuous imagination—and the triumph of hegemonic imagination in creating cultural interpretations of reality that reinforce privilege—help to explain much of the social toxicity in which the US is embroiled at present, particularly around issues of race, class, religion, and gender identity.

In this essay, I develop the concept of moral imagination as virtue, in conversation with the ethical writings of womanist (Black feminist) theologian Emilie Townes. I then argue for why moral imagination is integral to the social contribution of the liberal arts. Moral imagination depends upon other skills we more routinely associate with the liberal arts, namely critical thinking and creativity, but it also reminds us that the social endgame of the liberal arts goes beyond the critical and deconstructive. It empowers some of the other public-oriented capacities we consider important to the liberal arts, like multidisciplinary understanding, intellectual curiosity, empathic other-regard, cultural humility, and historical perspective. Properly understood, moral imagination equips individuals and communities to build connections with other people, communities, and moments across substantial difference.

Finally, to demonstrate its importance as an antidote to social toxicity, I will briefly discuss the relevance of moral imagination to current public debates around critical theory education, political tribalism, and ecological crisis.

Elsa Barraza Mendoza

Assistant Professor of History

A “Diseased and Noxious” Landscape: Toxic Geographies, Illness, and Slavery in the Maryland Jesuit’s Enslaved Estates, 1717–1865.

My project for this Faculty Research Seminar uses toxicity as an analytical lens to examine the living conditions of enslaved men, women, and children across the Jesuits’ plantation complex in Maryland and Washington, DC. This work will analyze how toxic geographies and hazardous conditions shaped the experiences of enslaved people under Jesuit rule, proposing that the intersection of racial capitalism, religion, and violence created the environment that defined their everyday existence.

The Society of Jesus was a major slaveholder across the Americas. However, most of the research on its slaveholding practices in the United States has focused on the theological underpinnings of their adherence to slavery, and most recently, on the sale of more than 300 people in 1838. This work will shift the focus to the long-running living conditions and health outcomes of generations who endured enslavement by this religious order. From 1717 to 1862, fevers, cholera, smallpox, foodborne diseases, and “tremors” were common at the Jesuit’s enslaved estates in the Chesapeake, from their urban college at Georgetown, in Washington DC, to their plantations scattered across Southern Maryland.

This research offers a view from the bottom, using medical humanities to analyze health and healthcare in different settings: an urban school and rural plantations. It uses administrative records, correspondence, diaries, financial ledgers, and sacraments to reconstruct how enslaved people experienced illness, nursed each other to health, and died during epidemics in the Jesuits’ complex of enslaved estates. By focusing on the health and medical experiences of enslaved men, women, and children, this article will depict the structural factors behind their living conditions, the challenges of their labor conditions, and their exposure to disease while toiling for the profit of Catholic priests in the United States.

Patricia Saldarriaga

Professor of Luso-Hispanic Studies

Toxicity and the Making of a Monster

I am currently working on a book project (in co-authorship with Emy Manini) titled Monsters vs. Patriarchy: The Rise of the Scapegoat in Global Cinema. During the course of these semesters, I will be working on two chapters: “Canibalia,” and “The End of Anthropos.” While the first chapter studies the gory way cannibalism has been used as a colonial tool to perpetuate oppression of female subjects, the second one studies shapeshifters and interspecies monsters.

A theoretical perspective on toxicity will enhance the way issues of race, gender/body, affects, and the environment can be treated in relation to monstrosity.

The making of a monster, from the very beginning, as pointed out by Antonio Negri, is linked to the notion of eugenics. What constitutes monstrosity, in many cases, has to do with a kind of deviation from what is considered normal. Exploring the connection between eugenics and toxicity in racialized bodies would allow me to explain why Latino bodies are considered monsters that need to be sterilized and eliminated in movies such as Madres (Ryan Zaragoza, 2021). Eugenics, on the other hand, has always been linked to the environment, especially through the notion of deep ecology that popularized during the Nazi regime. In the very same movie Madres, people believe that infertility is linked to chemicals in the environment. However, as explained at the end of the movie, doctors are performing sterilization on unsuspecting Latina women, as the women themselves, and their fertility, are what is perceived to be toxic to white society. Lines between environmental toxicity and eugenics in this and other movies are almost imperceptible. I would like to learn how to express this connection with a more targeted theoretical foundation. What we try to do in the book is point out parallels to historical and current events on different political and philosophical levels. In that sense, the movie resembles what happened in ICE camps with Latinas, Blacks and Indigenous women during the Trump administration. I also would like to focus on the pathologization of the body and explore the connections between toxicity and the making of the monstrous body. Can menstruation, (and its counterparts of menopause and aging), be considered a toxic fluid that determines the rejection of menstruating women in many societies? How is it that we have culturally construed menstruation as a toxic component of feminine bodies? How is it that new female monsters can resemantize menstruation?

To sum up, I believe that my participation in the seminar on toxicity would provide me with the theoretical knowledge needed to enhance my definition of monstrosity throughout the book. Precisely because the book focuses on female bodies that have been turned into monsters within a heteropatriarchal society, it would be of great help to delve into theories of toxicity that apply to issues of race, gender, the environment, medicine, and others. Listening to my colleagues will also give me a better idea of how this notion can be applied within the humanities. In the long run, my participation in the seminar will also improve my teaching. Courses like span0489 “Making Monsters” (cross listed with GSFS) or my summer course titled “Political Monsters in Cinema from Latin America and Spain” could very well benefit from my knowledge on toxicity.

Jacob Tropp

John Spencer Professor of African Studies

“Transnational Networks of Nuclear Suffering: Solidarities between Diné (Navajo) and Japanese Activists in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s”

Project abstract: The toxic impacts of uranium mining on the Diné (Navajo) peoples of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah in the late 20th century – from high cancer rates among Diné mineworkers and their families to the contamination of local reservation resources – have now become well known in both scholarly and popular accounts. Yet much less understood is how these experiences were significant on a global stage. In my ongoing work on this topic, I have investigated how Diné activists strategically utilized various opportunities in the late 1970s and early 1980s to globalize their toxic predicaments, connecting their local problems with those of other marginalized groups similarly contending with settler colonial legacies and the expansive power of multinational uranium corporations (specifically, Aboriginal communities in Australia’s Northern Territory and Namibians opposing apartheid South African control). My project for this year’s “Toxicity” Research Seminar explores another particularly revealing and previously unrecognized dimension of Diné transnational networking in these years: the development of solidarities with Japanese activists from a variety of environmental, antinuclear, and peace movements. At rallies, workshops, and conferences across the U.S. and Japan – from the Navajo Reservation to Nagasaki – Diné and Japanese activists found common ground in their shared histories of nuclear suffering, past and present. Moreover, through these exchanges, Diné participants’ personal accounts of uranium mining’s toxic toll had a transformative effect on many Japanese activists’ understanding of the nature and scope of global nuclear problems. On one level, these dialogues helped foster a growing awareness within Japanese antinuclear and peace organizations of the need to expand activist efforts beyond conventional concerns over bombs and energy production, to confront all stages of the nuclear fuel cycle and their toxic impacts – from uranium mining on indigenous lands in North America to nuclear waste dumping’s effects on Pacific Islanders. At the same time, Diné activists utilized their access to Japanese international networks and platforms to highlight how the nuclear suffering they and other Native American communities endured was intimately tied to deeper questions of indigenous sovereignty and survival.

’Translation Studies‘ Seminar Participants

Marybeth Nevins

Associate Professor of Anthropology

Seminar Leader

Hobos and Healers: The World Legacy of Indigenous Californian Communication Networks

My project treats enduring linguistic and social innovations that emerged from and circulated far beyond the contact zone between Maidu, Wintun and early gold rush immigrants. These “squatter” and migrant labor communities were formed within some of the same communicative networks that spread the Ghost Dance and other decolonial religious movements (Du Bois 1939. Hittman 2010), and have their own forward legacy in early 20thcentury labor movements, as well as in the formation of the northern California rancherias. They also left imprints and use-patterns on the northern California landscape in camps, one of which is named “Hobo Heaven,” that endure to this day. I examine Shipley’s (1956) and Dixon’s (1912) Maidu texts, Du Bois’s Ghost Dance survey (1939) and Dorothy Lee’s Wintun writings for what they reveal about indigenous and immigrant communicative dynamics on the post-gold rush landscape. My project places the expressions of indigenous speakers in early twentieth century linguistic text collections within what Jan Blommaert proposed as a sociolinguistics of globalization, bridging ethnography of communication and Wallerstein’s world-systems theory. This project brings Chase-Dunn and Mann’s (1998) adaptation of world systems theory to indigenous California together with what we know of widely circulated word of mouth texts in late nineteenth to early twentieth century in order to demonstrate the constitutive part played by indigenous communication networks in this world-forming epoch.

Karin Hanta

Director of the Feminist Resource Center at Chellis House

The Translator As Reconciliator: How Astrid Berger “Repatriated” Exile Writer Eva Kollisch In The Austrian Literary Field

My research lives at the intersection of translation studies and exile and Holocaust studies. In my dissertation and monograph, “Zurück zur Muttersprache: Austroamerikanische ExilschriftstellerInnen im östereichischen literarischen Feld” (Back to the Mother Tongue: Austro-American exile writers in the Austrian Literary Field) (Mandelbaum, Vienna, 2020), I investigated the role of translation in the creation of Austrian memory culture, as it relates to the Holocaust and Nazi-induced exile. I interviewed 6 writers who were able to escape Austria as children and started their literary career in English as well as 20 translators and publishers of exile literature and cultural brokers from governmental and non-governmental institution devoted to Austrian memory culture. I established that translation on a literal and metaphorical level had a bridge-building function where the trauma that the exile authors suffered was especially heeded.

Taking my research forward, I have examined translators’ subjectivity in greater detail. I am specifically looking at the inter-generational collaboration between Eva Kollisch, one of the founders of women’s studies, and Austrian translator Astrid Berger. I argue that the translator’s role is not only a bridge-building one, but also reconciliatory. I bring my vision of this translator’s role in conversation with Michael Rothberg’s concept of implication in histories of violence, thus adding further nuances to a much-discussed topic in Translation Studies—the translator’s subjectivity.

Renee Jourdenais

Professor TESOL/TFL

The development of professional identity: A case study of translators and interpreters in training

This project explores the ways in which novice interpreters and translators come to perceive and integrate their professional identities during the course of their MA studies. Of particular interest are the ways in which authentic learning activities, such as those provided in the interpretation and translation practica, help the students connect classroom learning with professional practice and see themselves as engaged, knowledgeable professionals. While there has been considerable research done in recent decades on the definition of skills required for the interpreting and translation professions, there is very little research on the development of interpreting and translation professionals.

During the past academic year, a colleague (at San Francisco State University) and I collected weekly journals and monthly interview data from four interpreting students at the Institute as they engaged in their final year of study and participated in interpreting events in the local community through their Interpretation Practicum. We are currently following three of these students as they begin their first year (post-MA) of their professional careers. During this academic year, we will be engaging translation students in a similar way: meeting with final semester students as they enroll in their Translation Practicum, in order to see the ways in which they perceive of and engage in the translation profession. We’ll also be inviting the incoming translation & interpretation students to participate with the hopes of following their development during the course of their two-year MA program.

Rebecca Mitchell

Associate Professor of History

Untempered Existence: Ivan Wyschnegradsky and Microtonal Music in Interwar Europe

My article-in-progress explores the translation of ideas from one cultural context to another through a case study of Russian émigré composer Ivan Wyschnegradsky (1893-1979). After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Wyschnegradsky joined thousands of other Russian émigrés in Paris. However, in contrast to many of his exiled compatriots, Wyschnegradsky sympathized with the Soviet project of building a revolutionary new society and sought to express his visions of a new world through his microtonal music as well as his philosophical and theoretical writings. I explore Wyschnegradsky’s navigation of Russian and French cultural worlds and argue that he emerged as a transnational mediator caught between worlds: while his pro-Bolshevik sympathies alienated him from Russian émigré circles, his work resonated with French avant-garde circles in the 1930s. This very success, however, was predicated on a process of “cultural translation” that stripped his compositions of key aspects of their philosophical basis. Through examining Wyschnegradsky’s public and private writings in French and Russian, I uncover these disparate identities.

Stefano Mula

Professor of Italian

Translation Between Politics and Ecdotics: Ignazio Silone’s Works in the 1930s

The Italian novelist and politician Ignazio Silone (1900-1978) was forced to leave Italy during Fascism, and wrote his first literary works while in exile, between Switzerland, France, and Germany. His first novel, Fontamara, was originally published in German, and soon in many other languages, its Italian version, appearing clandestinely in Switzerland a few months later, was never officially distributed in Italy.

Silone’s only and early novellas were also first published in a German volume, and the Italian originals have not yet been found. Silone enjoyed great popularity abroad, also for his political positions against fascism, while being almost unknown in Italy before WW2. After the war, he rewrote most of his early works, but his political positions (having left the Communist party and being at the same time critical of the Catholic Church) limited his fortune at home.

My project has two main goals. The first is to assess how politics played a role in how Silone was read and appreciated abroad, with a particular focus on how translation and his political positions helped and hindered at the same time his reception both abroad and in Italy. How did Silone’s antifascist position influenced the decision to translate his works, and then the translations themselves? The second is related to ecdotics, and the reconstruction of his early texts: what is the status of a translation in the (re)construction of a text? How to deal with variants imposed by censorship? What about changes introduced by translators, and later adopted by the author in a second version of a novel? Additionally, and lastly, I intend to explore how translations have often been neglected in the study of Silone, often with the consequence that his pre-WW2 reception was illogically based on readings of his post-WW2 rewritings, and not on the original texts, or better their many translations, on which Silone’s fame rested.

Jennifer Ortegren

Associate Professor of Religion

New Women, New Muslims: Gender, Class, and Religion in Contemporary India

I have proposed and am presenting work related to ethnographic research I conducted in Summer 2022 on class mobility among emerging middle-class Muslim women in urban India. The focus of the broader research is: 1) how women are redefining middle-class values and practices as Muslim values and practices and 2) how class mobility is reshaping relationships between Muslim and Hindu neighbors. Specifically, I am developing a conference paper and article related to girlhood as a time of boundary crossing when Muslim and Hindu girls become close friends, which shapes how their families engage and think of one another and how these young women continue to think of themselves as having interreligious friendships even when they move into homogenous conjugal homes where they do not interact with women from other religious traditions.

For this seminar, I’m interested in thinking about translation at three levels. First, I will literally be translating fieldwork conversations from Urdu and Hindi into English. I had a research assistant in India help transcribe and translate recordings while there, but am still facing critical decisions about which terms and religious concepts to translate in my writing (as opposed to retaining the original Urdu and Hindi) and, where I choose to do so, how best to translate them. Second, as part of the broader project, I’m thinking about how Muslims “translate” “Islamic” terms into “Indic” frames, and vice versa. By this, I mean understanding when, how, and why Muslim women explain Islamic ideas, practices, and concepts in ways specifically marked as Indian, when they appeal to a broader, global Muslim community, and what those differences may reveal. As tensions between Muslims and Hindus continue to rise in contemporary India, thinking about this “translation” practice is critical for understanding present and future relations. Third, I’m thinking about if and how, at the analytical level of the scholar, we can “translate” religious concepts from one tradition into another to make sense of ideas for ourselves and our readers.

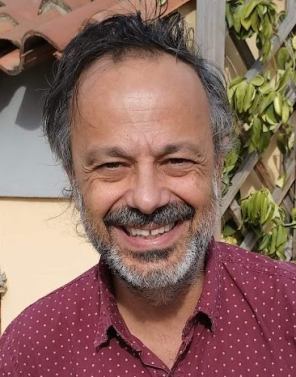

Fernando Rocha

Professor of Luso-Hispanic Studies

Afro-Brazilian religions in Afro-Brazilian literature: Translating across the Atlantic

One of my present lines of research focuses on Afro-Brazilian religions and how they are represented in and constitutive of various cultural objects, be they literary pieces, films, or songs in Brazilian popular music. Terreiros, the communities that have formed around Afro-Brazilian religious practices, have been a space of resistance against Eurocentric colonialism and anti-blackness. Mentions to Afro-Brazilian religions appear in canonical works, such as Mário de Andrade’s Macunaíma (1928) or Jorge de Lima’s Poemas negros (1947), and are even recurrent in the works of celebrated author Jorge Amado. More recently, as literature written by black Brazilians gain more space in academia and publishing houses (such as Mazza, Ogum’s Toques Negros, or Malê) focusing on their works gain more recognition and distribute their works, Afro-Brazilian religions occupy new spaces. Their disseminated presence — never limited to the geographical space of the terreiros — in the lives and experiences of those who embrace them begin to compose new texts in Brazilian culture, as we see in Cidinha da Silva’s crônicas or in Muniz Sodré’s short stories. For the Humanities Faculty Research Seminar, I am interested in exploring the translatability into English of texts that incorporate the experiences, concepts, and language of Afro-Brazilian religions, particularly in view of Afro-diasporic dialogues. In this sense, I am also interested in the work that academics such as Geri Augusto and Denise Carrascosa have been doing on translation across the Black Atlantic.