Shakespeare as Restoration

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

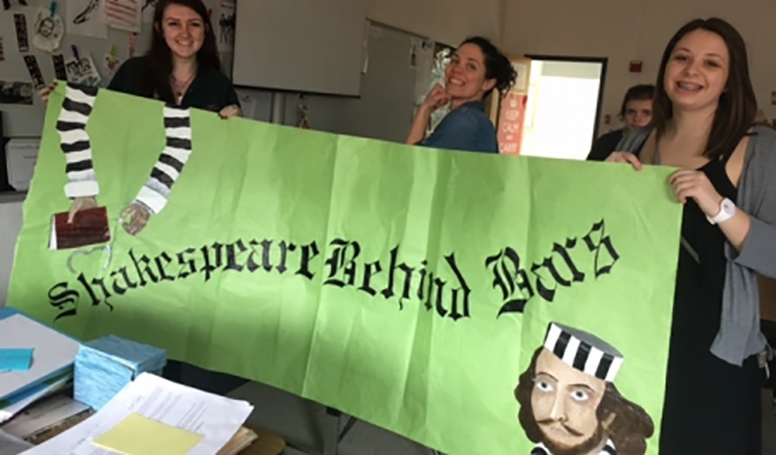

I suppose Frederick Douglass was quite right. As a teacher I find fixing folks (if that is even the appropriate way of thinking about it) is often more difficult than trying to form them from some point of beginning. But the business of building and repairing sturdy humans can’t be an either/or affair. One can, in fact, inform the other. It is this belief in the capacity to build strong children through healing broken men that drives my community literacy work with Shakespeare Behind Bars.

Based on a community engagement structure established by Carnegie Mellon Professor Linda Flower, the Shakespeare Behind Bars community literacy project was born out of a critical consideration of my own communities of participation—most notably my work at Bread Loaf as a Kentucky State Teacher Fellow and a member of the Bread Loaf Teacher Network. Consequently, multiple Bread Loaf professors informed this sort of hybrid classroom experiment in using Shakespeare performance and the public work of rhetoric for the promotion of literacy in prison. Professor Cheryl Glenn helped me to develop a rhetorical framework focused not simply on awareness of community partnerships but also on community action. Professor Emma Smith offered up suggestions for texts to help frame our conversations about Shakespeare performance and prison literacy including the Atlantic piece “Why Shakespeare Belongs in Prison,” as well as books by Laura Bates and Amy Scott-Douglass. And, as always, Dixie Goswami provided encouragement by emphasizing the importance of doing public work that extends beyond the classroom.

With all these resources in place, I have the task of convincing my students that promoting literacy for prisoners is a worthwhile enterprise, a process that will make us strong. This is no easy sale. When introducing this project to students, I first ask them to think about the purpose of prison, and students are typically quick only to identify the punitive function of incarceration—prison as punishment. Some students resist the idea that our time should even be spent on people who have committed horrific crimes. Others struggle with reconciling the use of Shakespeare (so often seen as impossibly fancy and inaccessible) in a place like prison. Put simply, many of my students have a hard time making any connection between their lived world and the world of our community partners in prison.

But then I see things begin to change. As students encounter the various texts giving shape to our community engagement project (the Shakespeare Behind Bars documentary, the Frontline episode “Prison State,” and the TED Talk “We Need to Talk about an Injustice,” among them), the disconnect begins to dissolve. Students read a thank you letter to our class from inmate Hal Cobb; he writes of what playing Prospero has taught him about atonement. Students talk to Shakespeare Behind Bars founder and producing director Curt Tofteland via Skype, and he tells the class that practices of empathy and human repair are worthy but also brutally taxing. “You have to be okay with your heart being broken,” he says. Tragedy comes with the territory.

And then it happens. These inmate participants, once distant and invisible, become our familiars. They, too, are part of a community of learners, within walls but just like us—wrestling with text to make sense out of uncertainty. Through the project, our two communities merge, if only briefly, in an exchange enabling both creation and restoration.