Writing from the Edge

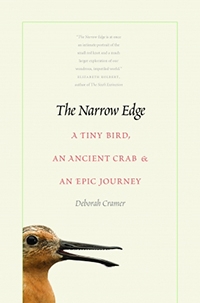

In 2017, the Sierra Club named Deborah Cramer MA ’76 “one of nine outstanding contemporary writers whose words can make us reconsider or better appreciate our relationship to the natural world.” She’s also been praised by Al Gore and Bill McKibben. A visiting scholar at MIT’s Environmental Solutions Initiative, Cramer writes for Audubon, the New York Times, and the Boston Globe and contributed to the 2017 PBS American Experience film Rachel Carson. She is also the author of Smithsonian Ocean: Our Water, Our World (Smithsonian, 2008) and Great Waters: An Atlantic Passage (Norton, 2002). Her most recent book, The Narrow Edge: A Tiny Bird, an Ancient Crab, and an Epic Journey (Yale University Press, 2015), won the 2016 National Academy of Sciences Best Book award, the 2016 Reed Award for Environmental Writing from the Southern Environmental Law Center, and the 2016 Society of Environmental Journalists Rachel Carson Book Award. Part travelogue, part rumination, part warning knell, part paean to a small but majestic bird and an underappreciated crab, the book follows Cramer’s journey with the Calidris canutus, or red knot. In an interview with CBC’s Quirks and Quarks program, Cramer explains that her initial fascination with the two species stemmed from a chance encounter on a beach with thousands of horseshoe crabs crawling ashore to lay eggs. The following day, she discovered thousands of shorebirds feeding on those eggs. She decided she needed to follow these tiny “red knot” sandpipers, remarkable for their marathon 10,000-mile journeys, and the crabs, remarkable for their 450-million-year longevity through five mass extinctions on earth. We wanted to probe Cramer’s tenacious devotion to telling their story as well as examine her own journey from Bread Loaf to science writing.

“Each year, students from 375 miles away [from San Antonio Oeste, Argentina, a beach where many knots stop to feed on their long migration north] raise money to spend the week with [biologist Patricia] Gonzalez on the beach, banding and resighting red knots. Their response is visceral: “Feeling such a small life in your hands,” one student, Cande Lorente, tells me, “you feel the importance of protecting it.” Emi Suarez describes the group as “The godparents of H3H,” a knot they banded. They eagerly follow H3H who, fattened on mejillines, worms, and clams, left San Antonio one spring on a nine-day, nonstop, 5,000-mile flight to Florida. “To hold a red knot and feel its beating heart,” Maria Belen Perez, another student, tells me, “is to feel the heartbeat of the Earth.” Harriet Lawrence Hemenway and Minna B. Hall would be proud. The mothers of conservation are alive and well.”

-Deborah Cramer, The Narrow Edge

When, how, and why did you enter the world of science writing?

Initially, it never crossed my mind to be a science writer. Holding a master’s in urban planning, I worked with local and state government to bring about a more equitable distribution of health and mental health care. I went to Bread Loaf because I love to read. Great literature offers extraordinary insight, perhaps the best insight, of people’s complex motivations and actions. I felt this keenly, but never knew how I’d use it until, a few years later, I felt compelled to write about the marsh behind my home, a marsh heavily polluted but still exquisitely beautiful. I walked it again and again, read scientific papers about marshes, and wrote an essay, published in the New York Times. The seeds for everything about that essay—its structure, content, perspective—were sown at Bread Loaf.

What are the greatest lessons you learned at Bread Loaf?

Stephen Donadio’s classes on Thoreau and Whitman, Richard Brodhead’s on Melville, and Lawrence Holland’s on Faulkner revealed immensely rich, powerful, evocative, and American views of our relationship to the earth: in Whitman’s sensuous immersion in the rhythms of the sea; Thoreau’s detailed observations of land he walks and rivers he paddles; Melville’s characters’ complex attitudes toward the ocean; and Faulkner, whose Yoknapatawpha County I felt and smelled on the page. I still see Robert Frost’s narrator peering into that well, and hear Thoreau in his canoe on the Merrimac, asking, “Who hears the fishes when they cry?” Bread Loaf showed me the power, the necessity, of conveying science viscerally.

You’ve read thousands of scientific books and reports and studies. Which have been most foundational or influential to your development as a thinker and writer?

I tried to choose. Can’t. The list would take up your entire newsletter.

In your research for The Narrow Edge, you traveled literally across the globe, you unearthed medieval University of Oxford menus featuring knots as fare, you visited a particle accelerometer at a PET radiopharmaceutical manufacturing facility, you tagged knots on beaches, you flew over a Texas wind farm, you learned how to fire a 12-gauge shotgun to protect yourself in the Arctic. Was there anywhere you weren’t willing to go to follow the story of the knots?

No. It helps to be open to where a story takes you. It helped not knowing details in advance. I might not have chosen to accompany a scientist chasing birds over the Laguna Madre if I’d known I’d be throwing up in his swooping plane all morning. It was worth every minute.

How many years did you spend working on the project?

Between three and four.

Besides patience, diligence, and dedication, what are the requisite qualities a science writer must possess?

I can’t speak for all science writers. To patience, diligence, and dedication, I’d add curiosity and humility: admitting what I can’t understand; querying scientists whose papers seem incomprehensible; taking hours, days, weeks, whatever is needed to understand those papers; waiting for the right stories—those rooted in strong science that illustrate a pressing point, that resonate; interviewing people without rushing to fill silences; writing and rewriting. I think I wrote The Narrow Edge six times.

Three years after publishing your book, what do you believe are now the greatest threats facing the red knots and other shorebirds?

,p.The number of shorebirds migrating through North America has declined by 70 percent. They are losing their homes and sustenance to development, erosion, storm surges, the conversion of wetlands to agriculture, overfishing, global warming.

Jonathan Franzen wrote recently in National Geographic about why we should care about birds. In your book, you present a strong argument based on our dependence on birds for their reduction of agricultural pests, for their dispersal of seeds and rebuilding of barren habitats, for their vital role in decomposition, for their nitrate- and phosphate-rich excrement, for their role in an intricate food web—the foundations of which, as you say, “may not be apparent until they fray, the value of individual threads unseen until the fabric is torn.” Do you believe the strongest case to be made for caring about birds, and about the red knot in particular, is a rational one, rooted in a commodification of birds’ usefulness to humans? Or is it an emotional one, rooted in appreciation for the dignity and beauty of these fellow creatures?

Cases for caring about birds are strong in different ways. Calculating nature’s monetary worth helps conserve nature. Though shorebirds may never “prove” their financial value until they disappear, if then, the monetary worth of their homes is huge. Salt marshes, for example, provide millions of dollars in storm surge protection: saving salt marshes saves shorebirds. Powerful arguments about birds’ “usefulness”—such as toucans dispersing seeds from nutmeg trees, ensuring the trees’ survival, or birds reseeding Mount St. Helens after the eruption—reveal the interconnectedness of nature and illuminate a beautifully woven web of life so much larger than ourselves. And beauty, beauty that touches peoples’ hearts, moves people deeply. Watching shorebirds arcing over the waves or lifting into a night sky, or horseshoe crabs emerging on a dark beach—moments where, a young woman in The Narrow Edge said, you can “feel the heartbeat of the earth”—I am filled with joy and peace and strength to fight for animals that have no voice at the tables where their fates are decided. We all share this earth. From an ethical standpoint, humans are relatively new arrivals, appearing—if you collapse earth’s animal history into one year—a few minutes before midnight on December 31. Who are we to decide who can stay and who must leave? God giving man “dominion over the fishes of the sea and the fowl of the air” is Genesis calling us to care for the Creation. My ideas about which of these views presents the strongest case aren’t relevant. I can’t save birds myself. When we are losing so much, we need every possible argument for why birds matter.

Why do we need humanities—and readers and writers—to tell us the stories of science?

Science is critical to addressing our pressing problems, but as is painfully evident, even the best research doesn’t always persuade. Understanding human experience and the human spirit—these are core concerns of the humanities. Great stories—those told by Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, Terry Tempest Williams, to name a few—touch people’s hearts, where in the end, decisions are made.

You also write that you’ve seen “evidence that a web, once torn, can be respun.” What gives you hope for the future of the horseshoe crab and the red knot?

We know what to do: we need will. It may be daunting, yet the dedication of so many people joining to give shorebirds safe passage—along the edge of two entire continents, across disparate languages, cultures, and politics—is uplifting and inspiring. The people, and the birds, are exemplars of tenacity and resilience, beacons of courage and hope. Readers drawn to The Narrow Edge are raising additional funds necessary to rebuild the Atlantic flyway. Others are calling for biomedical and pharmaceutical companies to further test and then adopt a synthetic substitute for horseshoe crab blood. This would happen more quickly if all of us who get vaccinated or have a flu shot demand that manufacturers test and use the synthetic. That should be easy, shouldn’t it?