The Project Cycle

What is the Project Cycle?

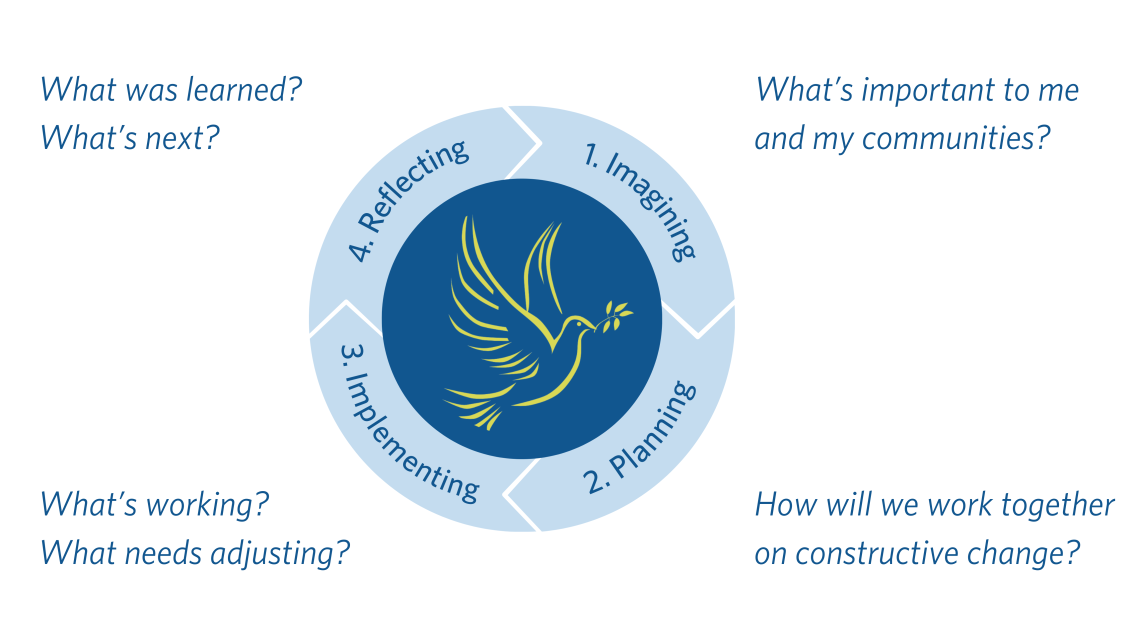

The Project Cycle is a management tool that can help applicants and grantees create thoughtful, meaningful projects. It can also help campus liaisons mentor their students.

It is composed of four stages: Imagining, Planning, Implementing, and Reflecting.

In the following subpages, you’ll find information about each stage, including an interview with Middlebury College campus liaison Heather Neuwirth Lovejoy, resources to help you work through your project, and prompts to inspire discussion, creativity, and critical thinking. This content is designed to help applicants and grantees apply the Project Cycle to their work.

Not every prompt will be relevant to everyone but all projects will move through these four phases. Keep in mind that the cycle doesn’t always move in one direction. It’s often necessary to take a step back and reconsider your next move, rather than rushing ahead.

Additional Resources

Relevant resources for peacebuilding project cycles will be added here as they become available. If you need further guidance, reach out to your campus liaison for support.

Is there a resource you find helpful that isn’t on this page? Send it to us and we might add it to this collection!