Hillel Hayom 2021

Reflections

Summer around here is for planning High Holidays. There are logistics to figure out, honors and roles to fill, sermons to write, and prayers to coordinate with our alumnus cantor, Aaron Mendelsohn ’95. And there is orientation to plan for—welcoming new and returning students to campus, introducing them to the work of the Scott Center for Spiritual and Religious Life, and working with student leaders around tools to help new students make a successful transition to campus.

With all the planning we need to do, it’s been particularly hard this summer, watching the Delta variant bump up the COVID cases throughout the nation and even here in Vermont. Once again we are anticipating and dealing with new restrictions and scenarios that ask us to pivot, to change our approach, to reinvent something we thought we had all set.

What I have come back to over and over again during this pandemic period is the way that Judaism has held, throughout its history, the tension between innovation and tradition. Its innovative spirit has allowed it to adapt to extreme circumstances such as the destruction of the Temple, exile, and persecution. It has also allowed adaption to less extreme circumstances, such as the pressures and opportunities presented by the majority cultures within which Judaism lives as its own civilization. At the same time, Judaism still maintains most of the traditional prayers, customs, and observances, in some form or another, that it has maintained for thousands of years.

So here we are again, innovating. We are adapting our High Holiday services to outdoor spaces and masked participation, to shorter services and different choreographies. And yet we know that as soon as the opening notes of the High Holiday nusach (melodies) reach our ears this year, as soon as that first bite of apple dipped in honey reaches our lips, we will immediately be present in the experience of New Year, new beginning, taking stock and looking forward with hope. Opening the machzor for the first time to begin planning services, I am reminded that as much as we may play with the liturgy from year to year—a new poem here, a shorter prayer there, a rearrangement of the order to allow for various circumstances—the words, the ideas, the wisdom, and the guidance remain the same. Return to yourself. Return to your community. Make a new start. Begin again with intention.

At the start of this New Year, may we all find comfort, familiarity, and deep wisdom in the repetition of our tradition. And at the start of this New Year, may we all find that spark of creativity and hope that comes with beginning something anew. Shana Tova u’Metukah. May you have a sweet New Year.

Yom HaShoah

Yesh Kochavim

Words by Hannah Senesh, music by Michael Bell

Eleanor Mayerfeld ‘19.5 voice, Michael Bell, guitar

There are stars

whose light reaches the earth only after they themselves have disintegrated

and are no more.

And there are people

whose scintillating memory lights the world after they have passed from it.

These lights –

which shine in the darkest night – are those which illumine for us the path.

Hannah Senesh, originally in Hebrew

English Translator unknown

High Holiday Sermons and Poetry

Rabbi Danielle Stillman’s Erev Rosh Hashanah Devar

Ben Dohan’s ‘20.5 Rosh Hashanah Day Devar

President Laurie Patton’s Kol Nidre Devar

Rabbi Danielle Stillman’s Yom Kippur Devar

“If You Can,” by Gary Margolis

“Arias and Arguments” by Gary Margolis

Inside Out Wisdom and Action

By Danielle Stillman

Mimi (Michal) Micner ’10 and I met last fall when Professor Rebecca Gould and I attended a training for the Inside Out Wisdom and Action (IOWA) curriculum in Boston. After a round of introductions, she shared that she was a Midd alum who was finishing her last year of rabbinical school at Hebrew College in Boston. Professor Gould and I already knew that this curriculum in teaching Jewish spiritual practices to help support social justice work would be a good match for our campus, and meeting Mimi there just confirmed it. I caught up with her over the summer to hear more about her work with IOWA and what she is doing now. If you want to read even more about her approach to change and spiritual practice, check out this longer interview she gave for the IOWA website.

Can you tell me about your connection to IOWA and how you got involved in it?

I got involved in the IOWA Project after meeting Rabbi David Jaffe through the JOIN for Justice Community Organizing Fellowship, which I did the year after I graduated from Middlebury. During the fellowship, I began to see the ways that Torah and the social justice issues of our time speak to each other, and I was curious to learn more. This brought me to a class that David was teaching about the relationship between our inner life and social justice work, and also brought me to learning with David one-on-one. We learned a Mussar (applied Jewish ethics) book called To Turn the Many to Righteousness, which was about some of the questions that those teaching Torah faced in their work, questions about responsibility, burnout, and relationships. I was so moved to read Torah that wrestled with the same questions I was wrestling with as an activist and organizer. That got me hooked into learning with David, and I have been learning and working with him since, and now with the IOWA Project.

How are spiritual practice and social justice work connected for you, personally?

Spiritual practice and social justice work are inextricably connected for me. The kind of transformation I want to be part of creating in the world lives not only at the policy level, but at the soul level. The work of opening and unburdening our hearts and changing culture are required for the success of the kind of policies many of us are advocating for. This kind of soul work can help expand our sense of imagination, and help us envision and reach for a world we might be otherwise too timid or constrained to imagine. There is something impossible about achieving a just, compassionate, and healed world in the absence of real spiritual work.

You just received rabbinic ordination this past spring from Hebrew College. Mazel tov! What are you up to now?

Thank you! Following our Zoom ordination, I began working as the rabbi of Temple Beth Torah, a small Conservative synagogue in Holliston, Massachusetts.

Did you imagine yourself pursuing the rabbinical path when you were at Middlebury? How did your time at Middlebury contribute to where you are today?

It wasn’t something I really considered at Middlebury. I was involved in the Jewish community and very engaged as a leader of J Street U, and I anticipated that my path would be more conventionally political. It was after Middlebury that I began to find a nourishing and powerful blend of spiritual and political work, and this is what pulled me to rabbinical school.

Any particular wisdom you would like to share from your journey so far? What would you say to any of us—current Middlebury students, alums, or parents—who are working toward a more just society right now?

My greatest spiritual advice would be to not give up on the world you want to see. We live in a status quo that makes itself out to be inevitable and unstoppable. This is far from the truth. The truth is that we are immensely powerful in our ability to shape our political and social reality, even though it may take a long time to see the results of our work, if at all. A lot of my spiritual work has been around hope and despair, and with the help of a lot of brilliant writers, I have come to see hope as being about leaning into the creative potential of uncertainty (thank you, Joanna Macy and Rebecca Solnit). We are always in the place of “maybe,” that maybe things could be otherwise if we do something. The fight for Middlebury to divest its endowment from fossil fuels began while I was a student, and it is amazing to see it finally happening a decade later. Imagine if people had given up. We just have to cultivate the capacity to tap into our yearning—our love for the world, our vision for the world—and allow ourselves to be sustained by that in the long fight for change.

Grounding Social Action in Spiritual Practice

By Danielle Stillman

We started our group in the living room of the Scott Center for Spiritual and Religious Life. It was J-term, and it was cold, so we poured hot tea as we settled into our places in front of a lit fireplace and began the session with a chant about gratitude. We were 11 students and one faculty member, with Professor Rebecca Gould and myself as leaders. While we came from a variety of spiritual backgrounds, we were there to learn from one another and ourselves about how spiritual practice could help ground and sustain social action, and we were using the wisdom of the Jewish tradition to do it.

Social justice and action have always been a huge part of college life. These days, they feel as urgent as they ever have, with multiple issues at hand, from systemic racism to the climate crisis to immigrant rights. With so much urgency, and with a sometimes-caustic culture within activist circles of “callouts” and egos, it is all too easy to feel burned out, rather than inspired, by one’s activism. Those challenging cultures can also derail the effectiveness of the activism itself. Organizers may want immediate results, when the situation may actually call for more patience. An uncompromising opponent may be better swayed by close listening than by demands.

The Inside Out Wisdom and Action (IOWA) Project aims to address all of these conditions by using traditional Jewish practices to help ground and guide people who are working for change. Based on a book of the same name by Rabbi David Jaffe, the program offers a curriculum to teach to small groups of students who want to grow spiritually in order to support the effectiveness of their social change work. They are introduced to practices such as journaling, meditation, and deep listening with study partners. The group worked with one virtue, or “soul trait” each session—a practice adopted from the Jewish practice of Mussar, an ethical practice of going deeply into a virtue to increase your capacity to practice it in life. Humility, trust, finding good points in oneself and others, and the significance of rest were just some of the virtues we worked on over the course of J-term and the spring.

Our group welcomed any member of campus, regardless of their religious or nonreligious background; the practices we taught through IOWA may have been drawn from Judaism, but the virtues we were working on were universal. We read Jewish texts right alongside texts from Martin Luther King and other traditions. We debriefed the experiences some of the students were having organizing on campus, and we offered group wisdom for approaching challenges that were arising on campus and within individuals’ lives.

Although the group ended on a Zoom call, with everyone in different locations rather than gathered cozily in the Hathaway House living room, the appreciation and gratitude were palpable through the ether. Professor Gould and I look forward to offering this group again to the next generation of students seeking change—for themselves and for their many communities.

Middlebury Students Take on Food Insecurity

By Molly Babbin ’22

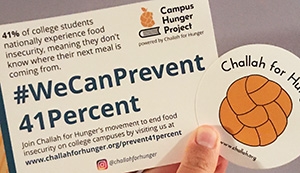

Last fall, about 25 Hillel volunteers, through the nationwide organization Challah for Hunger, baked more than 400 loaves of challah to raise money for anti-hunger organizations. In the nine hours of challah baking and selling, I was heartened by the way religion, culture, and our love of freshly baked bread could bring us together to think about the pervasive and multifaceted issue of food insecurity.

We ended up donating more than $1,360 to HOPE, a local food shelf, and Swipe Out Hunger, a national organization that works to eliminate food insecurity on college campuses, and this led me to think more deeply about the concept of charity.

In Judaism, the term tzedakah is commonly used to signify philanthropy or charitable giving. However, tzedakah also comes from the word tzedek, which translates to “justice,” and as Rabbi Jill Jacobs notes in her book There Shall Be No Needy, support for those in need of resources should be seen as an “obligation and as a means of restoring justice to the world, and not as an altruistic or voluntary gesture.” A well-known critique of charity is that it often addresses the symptoms of a problem and not the causes, and that those giving money are often valued over those receiving it. After reading Rabbi Jill Jacobs’s words, I wondered, How can we be more intentional about combating systemic injustices? How can we ensure that our work is reparative and not self-serving?

So this summer, Middlebury Hillel organized a four-part discussion group to engage with readings about systemic racism and the responsibility of Jewish people to be actively anti-racist. In these conversations, we unpacked that racism is not always obvious and immediately visible. Instead, it is an underlying system that is deeply rooted in many of our individual assumptions and Jewish communities, and it is further perpetuated by our overarching social and economic structures. As we continue to better understand that inequality is a result of historical and current systems, as opposed to individual actions, the “obligation” that Rabbi Jill Jacobs references becomes clearer.

Rather than viewing charitable endeavors as “heroic” or voluntary, it is expected that those with resources understand that they often have those resources because of the way that social systems privilege some and disadvantage others. It is imperative that they work with a sense of redistribution toward those who are harmed by those same social systems. It is through this analytical and reflective lens that we hope to continue our work with Challah for Hunger, transforming the once-a-semester fundraiser into a justice-focused initiative; we must ensure that students do not forget about the issue they are raising money for once they leave the challah-baking kitchen.

As we dove deeper into the issue of food insecurity, we realized that we could not donate money to off-campus organizations without also addressing food access among our own student body. Food insecurity is not something to be intellectualized, as it currently affects and/or has affected many of the lives of our peers and Challah for Hunger volunteers. According to the Hope Center, four out of 10 college students experience food insecurity, and that percentage is increasing due to COVID-19. College food insecurity also disproportionately impacts students of color. Middlebury is not immune to this issue: a survey conducted in Professor Molly Anderson’s course Hunger, Food Security, and Food Sovereignty found that nearly 10 percent of Middlebury student respondents either sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat when at school, with half of those respondents also reporting food insecurity over breaks.

In an effort to see the structural reasons behind campus food insecurity, we asked ourselves, Why aren’t students’ basic needs being met? We realized that there was no clear place for students experiencing food insecurity to learn where they could access support, food, and other resources. In response, Melanie Leider ’23, Bella Pucker ’21, Elsa Soderstrom ’22, and I developed a resource guide this spring, consolidating contact information for on-campus resources, food pantries, discounted grocery options, SNAP application resources, public transportation, and securing food over breaks. We publicized the guide though student organizations, College centers, and an op-ed in the Middlebury Campus (you can read it here). The resource guide was updated to support students who remained on campus after COVID-19–related closures, and it will be updated again in the fall of 2020. It can be accessed at go.middlebury.edu/foodresources/.

As the pandemic created a spike in the use of food pantries, we in Challah for Hunger felt the need to continue our fundraiser throughout the spring. Without the ability to bake and sell challah together, we transformed our typical bake sale into an at-home localized version in which we each baked loaves of challah and donated either to a local food pantry or to HOPE in Middlebury. Rabbi Danielle added an incentive to donate by deciding to match our donations, and in total we raised $640. We learned that our work did not have to end with Middlebury’s closure, and that we would have to break with tradition to confront the new barriers to food access created by the pandemic.

In addition to donating to community food pantries, we also understood the challenges unique to college students during this time. When we were evacuated from the College, I was amazed by the ways that many students put their community first, creating mutual aid spreadsheets and dedicating themselves to the fight for students’ basic food, housing, and mental health needs. In this spirit, and as student food insecurity began to climb, Melanie Leider and I decided to apply for the Campus Hunger Project Cohort for the 2020–2021 academic year. We completed training this summer and will conduct a project to support Middlebury student food access this upcoming year.

A list of resources is a good starting point, but looking forward, we hope to inquire deeper into why the resource guide was necessary in the first place. As colleges like Middlebury work to diversify their student bodies, they cannot expect academic success if they do not also take responsibility for meeting students’ basic needs. Just as COVID-19 revealed the food-access and wealth disparities in our society, it also exposed the inequities within university student bodies. Now, institutions must act on this knowledge and take responsibility for ensuring that all of their students have what they need to thrive.

Kneading Challah

by Lila Sternberg-Sher ‘21.5

“What was the highlight of your week?” This question was a favorite in the various Middlebury clubs and groups I was a part of during the first COVID college semester. With most of us at home struggling to find the motivation to continue with schoolwork, missing our friends, and grieving the loss of a semester on campus or abroad, identifying a good part of the past week could be a challenge. While sometimes my highlight was a FaceTime call, a phone call, or a Netflix Party with friends, there was one activity that became a treasured part of my Fridays in quarantine even if it wasn’t the one I chose to share: challah baking.

If you ask my friends and family, they’ll all tell you that I’m an avid baker. Before 2020, I was mostly interested in desserts. Nothing fancy, but I always enjoyed experimenting with recipes to create the most delicious brownies or chocolate chip cookies. I had baked challah before, as the Hillel co–meals chair and often at home over the summer. I’d played around with a few different recipes and had settled on a favorite. I’d also become a decent braider. However, calling myself an expert would have been a stretch, and I rarely got creative with my loaves.

My dream since early high school had been to spend time making my way through a cookbook: to essentially pull a Julie & Julia. When I realized that I would have several weeks between finishing J-term and departing for my semester abroad, I decided that this would be the perfect time to live out my plan. During those weeks, almost none of my friends from high school would be home, my brother would be away at school, and my friends from college would be busy starting their new semesters. Working my way through a bread book would give me purpose and keep me from loneliness.

To me, bread is one of the most magical things you can make. Although I don’t know all the chemistry behind it, I’ve watched enough of The Great British Baking Show to appreciate the importance of each step. Whereas with cooking, adding too much or too little of an ingredient at the wrong time probably won’t ruin your recipe, bread baking is more sensitive. Many professionals recommend using a scale to weigh the ingredients instead of using volume measures because it’s impossible to know how tightly things like flour are packed (i.e., one cup from one brand could be much denser than another, leading you to have significantly more flour in the first cup than the second). Kneading is also essential, to break down the gluten and give the finished product a softer texture. And, of course, rising. Although the layperson won’t notice an overproofed loaf, when my bread has risen too much, I joke with my family that Paul Hollywood would be very upset.

Excited about my plans for February, I dug up a yellowing copy of Beard on Bread that my mom had baked from as a teenager. Throughout those few weeks I made five or six loaves, not quite as many as I would have liked, but enough to keep me satisfied.

The process of making food, as well as the community that it brings together, has always been an important part of my Judaism. Whenever I’m introducing people to my Jewish identity, I like to do it with food. During my short time overseas, I was able to make two loaves of challah for my host family. Upon seeing me add more than a quarter cup of sugar, my Chilean brother asked, “Is that a sweet bread?” I had no idea how to respond. How can one possibly explain what challah is? It can be savory, sweet, or somewhere in between, and all of it is still challah. The two loaves I made for my host family were certainly not my best attempt, but they were appreciated nonetheless. While my stay with my host family ended abruptly with the closing of both the American and Chilean borders, and the cancellation and evacuation of my program, I left having shared a special part of my people’s heritage and tradition.

After arriving home, I began to grieve. Attending Zoom classes in Spanish at the dining room table in my childhood home was not the adventure abroad I’d worked so hard for the past year and a half to make happen. I knew that what I needed at the start of this incredibly tumultuous and destabilizing time was some sort of constant. So I began making challah. It soon became something that I had to do, an activity required to maintain my mental health. Every Friday at noon when I would get out the flour, the sugar, the water, the yeast, the honey, the eggs, I knew that by that evening I would have kneaded my stress away.

In the beginning, I would make two large loaves every Friday. We’d eat half of one (maybe a whole one if we were feeling hungry) and the rest would be tucked in the freezer for later. Soon the freezer was overflowing, so I gifted loaves to friends and extended family. By mid-April, it was clear that many others had caught on to the virtues of bread making, leaving yeast in short supply. Luckily, my Beard on Bread endeavor meant we were still stocked up.

Before long, my Fridays involved experimenting with new recipes. Each week, Middlebury Hillel’s Jews News would include a challah recipe sent in by a member. There were variations on regular loaves, cinnamon sugar loaves, Rabbi Danielle’s whole wheat rosemary loaves, cheesy garlic loaves. If I saw a recipe that intrigued me, I would bookmark it for later. On the Fridays when I had more time and was feeling adventurous, I turned to these for inspiration.

I love the ritual that goes along with making and eating challah, as well as the room that is left for improvisation. On weeks when I’m feeling more audacious, I might put an exciting filling inside each strand (maybe chocolate chips—a Hillel favorite—or sundried tomatoes), add a fun spice to the dough (will it be Jordanian za’atar brought back for me by a close friend after her semester abroad?), or switch out a cup of all-purpose flour for a cup of whole wheat. Sometimes, instead of doing my typical six-strand braid, I try my hand at four strands or even a double-decker design.

In a time filled with so much uncertainty and instability, I feel grounded by the structure and creativity of my weekly challah-making practice. I know that whatever I attempt, I’ll always be able to put a golden-brown, homemade loaf on the table and share my creation with loved ones. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got some bread that needs braiding.

Challah Recipe

Interested in baking challah at home? Here’s a terrific recipe frequently used by Hillel when we bake at Middlebury. Let us know how it turns out!