Assignment Ideas

On this page, you’ll find ideas for scaffolded assignments that make it easy for students to learn to love doing research, one step at a time. Foundational information literacy concepts like where to begin, how to develop a question, how to join the scholarly conversation, how to critically evaluate sources, and how to cite sources, can be overlooked when they’re wrapped up in the larger process of researching and writing a long paper. Shorter exercises give us a chance to encourage students to hone each research-related skill individually.

Tip

Talk with your librarian and see what makes sense in the context of your class. Your librarian will be able to answer questions and brainstorm, help you design an assignment, walk your students through an assignment, and more.

How to Begin Doing Research

- Dissect a scholarly journal article (or a book chapter): How did the author organize their article? What kinds of sources did they use? Might any of their sources be useful to you?

- Encyclopedias and other reference works can help you find and develop ideas for a research topic. Go to a discipline-specific encyclopedia and search for an essay related to your topic. Probably, you will need to think broadly about your topic in order to find something about it. Once you’ve found an essay, describe how it could help you work more on this topic. [NOTE to faculty: Our Reference Guide recommends alternative online reference sources.

- Watch Top Tips for Starting Your Research. Then, think of a time when you did research on your own. Share one tip that you would recommend adding to the Top Tips video.

- Create a five-step research plan for incoming Midd Kids. For example, “Step 1: Collect a handful of topics to research…” Follow your own research plan and adjust as necessary.

- Help students choose a research topic. First, students answer a prompt: What did you imagine you’d be able to learn about in this class? Students then pair up and ask one another questions: What strikes you as most interesting about those topics? Finally, each student selects one topic, writes a strong statement about it, and lists a few arguments that they expect to find in their research. The students can use these arguments as subtopics for an exploratory literature search. [Thanks to Professor Hector Vila for the idea!]

- Help students warm up to a longer research paper. Students record a two-minute oral presentation. The presentation must answer essential questions about a narrow topic. For example, a student might choose a historical figure and explain who the person was and why they were important. [Thanks to Professor Sarah Stroup for the idea!]

Develop a Research Question

- Dissect a scholarly journal article or book chapter: What question did the authors ask? What is their answer?

- Draft a research question for an imaginary research paper (you won’t actually write the paper).

- Pick a topic for an imaginary research paper. (You won’t actually write the paper.) Then, revise your topic by following the advice we provide in Top Tips for Starting Your Research. Describe how and why you revised your topic.

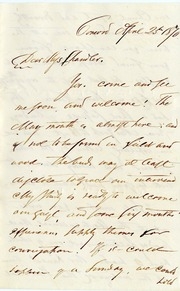

- Select specific online primary sources (especially from Middlebury’s collection of over 14,000 rare books, archives, and more) in order to model document analysis and historical thinking through directed, specific prompts, like “Who created this?” and “What questions does it raise?” Ask students to identify questions for further investigation, and offer strategies for how to answer them.

- Give students a dissertation by a well-known scholar and have them find related articles and books by the same author. Then, have students discuss how the author revised their research question over time.

- Have students generate questions about the historical events that provide the setting for a literary work, then try to find answers to the questions. Afterwards, invite the students to reflect on the process of using a question to guide their research.

Join the Scholarly Conversation

- Dissect a scholarly journal article (or book chapter): Identify one outside source that the author of your article refers to several times. Does the author of your article agree with it, or do they disagree? Pick a few specific passages in which the author refers to and agrees/disagrees with the outside source.

- Research a topic, then write 2-3 sentences of agreement (or disagreement) with one of the sources you’ve found.

- Pick a single primary source (from our collections or beyond). Ask students to analyze the source, read it closely, and summarize it. Then, ask them to find 2-3 primary and secondary sources that support, contradict, or deepen their understanding of the original source.

- Have all students read the same article, then write a commentary about some element in the article about which they feel strongly. The commentary should be concise and well supported, and students should be assured that if they take a critical stance, that doesn’t mean rejection, merely critical evaluation. Students should post their commentary to a class discussion board, then thoughtfully respond to at least one other opinion (activate a setting requiring users post before seeing replies). [Thanks to Professor Eric Moody and librarian Wendy Shook for the idea!]

- Show students that the creation of information is a process, not something that occurs at a single point in time: Have students analyze how an event is written about over the course of severalyears, tracing the progression from newspapers to magazines to scholarly articles.

- Have students trace the development of a medical treatment. Include a discussion of how current research has changed earlier medical practice or scientific understanding.

Tip:

The book They Say, I Say provides practical advice and examples that can help students learn how to enter the scholarly conversation.

Evaluate Sources

- Have students watch an instructional video about scholarly authority, then analyze the coverage of a topic by investigating different types of materials (popular vs. scholarly, primary vs. secondary). Additionally, students could describe the goals of each form of writing.

- Find a popular article in a magazine or newspaper article that is based on scholarly research, and have students track down the sources that were used. Students should describe how well the facts are presented, and whether important findings were misrepresented. This assignment might work best for topics related to science, health and public policy.

- Find a persuasive editorial that does not cite sources for its claims. Have students look for evidence, then rewrite their own version of the editorial with sources acknowledged.

- Choose one book from your course reading list. Have students find and read 2-3 reviews of the work, then write a response to one of the reviews.

- Choose an article that has been heavily critiqued by scholars. First, have students read the article and submit their own response. Then, have students research the article to and respond to what the critics have said. Bonus: Have students reflect on what they learned about evaluating scholarly sources.

- Assign an article that was based on industry-funded research (common topics might include smoking, obesity, health effects of particular drugs or products). Have students check the author’s affiliations and note the funding source for the research. For background, have students read articles that discuss industry-funded research. Example: Coca-Cola Funds Scientists Who Shift Blame for Obesity Away From Bad Diets.

Cite Sources

- Have students compile an annotated bibliography on a topic that they’re investigating for a research paper. Be sure that in each annotation they describe how they might use the source. You may wish to direct students to our Annotated Bibliographies Guide, and our Citation Guide.

- Use the Academic Integrity Tutorial. It creates opportunities both for students to ask questions, and for faculty to demonstrate that identifying the best course of action sometimes isn’t easy.

- Have students take the Tutorial outside of class, and ask each student to pick one question to discuss in class. (Alternatively, discuss all of the questions that the students answered incorrectly.)

- Have students take the Tutorial outside of class. Do not check the results, and don’t ask students to share. Instead, discuss all of the answers. (Bonus if you take the tutorial and get some answers wrong; this can serve as a useful discussion point too.)

- Put students in small groups and have each group take the Tutorial during class. Then, as a class, review all of the answers together.

- In a first-year seminar, you might pair the AIT with a ceremony around the class’s virtual signing of the pledge.

- Watch Citation for People Who Hate Citation and write one question that you would add to Middlebury’s Academic Integrity Tutorial.

- Do some backwards-engineering of the in-text citations (or footnotes/endnotes) in a scholarly journal article. Which sources seem to have formed the foundation for the main idea that the author presents? Does the author provide at least one source that suggests the existence of a counter-argument?

Research Within a Genre

- Give students a scholarly article from your discipline, then ask them to identify its key elements and compare them to those of a magazine article.

- Literature Review: Have students read the literature review section of an assigned journal article. Then have them write a literature review with bibliography on another topic.

- Have the students read a critical analysis of a theatrical performance. Have students describe the types of sources cited and how the sources are used.

Special Collections & Archives

- Contact us at specialcollections@middlebury.edu to learn about curated primary sources on your course topic, exhibits, class meetings, mini lectures, and more.

- Introduce students to the history of the book, the dissemination of text, materiality in a digital environment, and other hands-on, creative experiences.

- Help students search the Internet Archive at Middlebury for digital copies of items in our collections including photographs and films, unique manuscript items, letters, maps, Middlebury College yearbooks and newspapers, College documents, and more.

- Give students experience navigating finding aids for archival and manuscript collections in ArchivesSpace, our online Special Collections inventory.

Brainstorm with a librarian

When you’re to start planning a research workshop, contact your library liaison.

Or, chat with any librarian at the Research Desk!

Research Desk

- Email:

- ResearchDesk@middlebury.edu

- Tel:

- (802) 443-5496

- Office:

- Davis Family Library