Middlebury Language Schools in a Book of Poetry

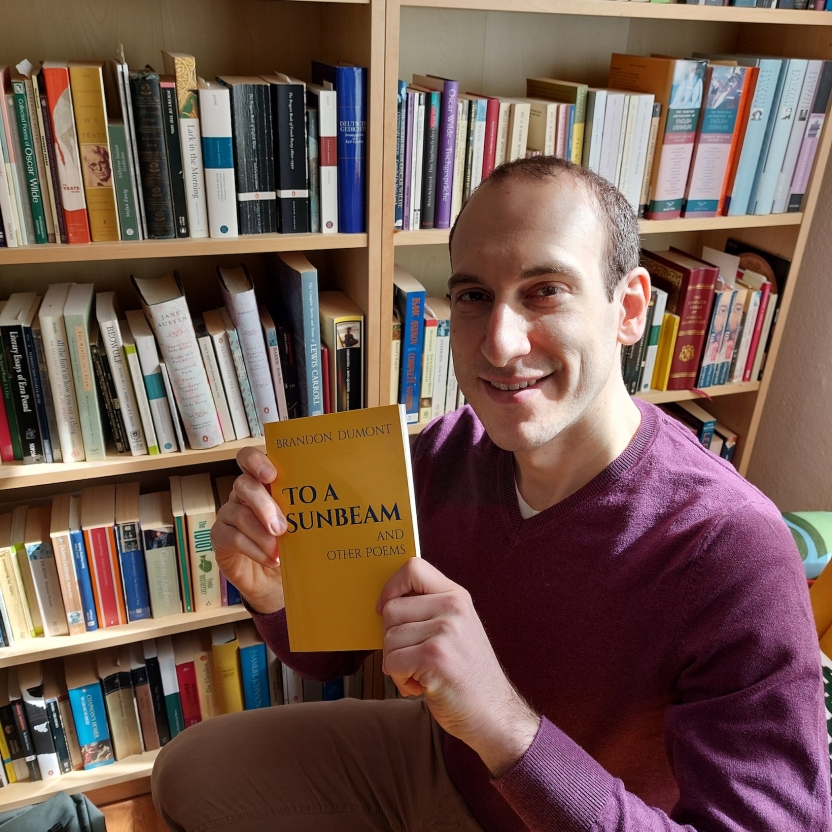

Brandon Dumont, German School 2009, describes his summer at the Middlebury Language Schools as one of the best summers of his life. Several of the poems included in his book, To a Sunbeam and Other Poems, were inspired by his Middlebury experience. He recently shared his writing journey with us.

I participated in the Language Immersion Program for German at Middlebury College in the summer of 2009. Because of the high demands of the program on us daily, we looked forward to the respites between sessions of study. At meal-times we talked, cheerfully and clumsily, as far as our vocabulary could bring us; we were valiantly fastidious about our pledge not to allow a single syllable of English to cross our lips, and if we didn’t know enough words to clothe the pose of our thoughts, we took humorous and elaborate linguistic detours to make ourselves finally understood. It was enormous fun. We ate heartily, and we were very happy. In the evenings when we gathered for supper, we could see through the tall windows of the mess-hall the hills struck golden by the sinking sun. Since I would be off to Germany within a few months after the program to continue my studies, those hills seemed to roll gently away toward some tantalizing and unseen limit, like a warm invitation to a beautiful future.

A few years after the program, when I tried to capture in a poem the wonderful feeling of savoring a prospect while looking out onto a beautiful, natural vista, it was that view from the mess-hall which was my inspiring model:

We watched and wanted breathing:

So amazèd we;

For all the varied glories

That are yet to be

Came forward as these pastures,

Urged us as the sea,

To set brave sail upon them —

Faith, the only fee

In our dreams becoming

Once reality.

—excerpt from “Possibility”

This year I published a book of poetry titledTo a Sunbeam and Other Poems (2023), and it is with this poem, “Possibility,” that my book begins. But this little ode to the future is not the only shape my time at the Language Schools takes in my book; the last poem, a long and ambitious one, was also inspired by an experience I had at Middlebury.

While we in the general program were busy merely learning how to decline adjectives or form questions with the second-person subjunctive, the participants of the German for Singers program were also learning the finest points of performing works from the great repertoire of German art-songs. They studied pieces by composers such as Brahms, Mozart, or Schubert, and performed them publicly at recitals throughout the summer.

It was at one of those recitals in Robison Hall one evening midway through the program where I heard for the first time three songs by the composer Hugo Wolf (1860–1903). Till the last chord sounded, my enthralled attention watched every melodic swell and climb, and sank into the luxury of every harmony. These works fit my soul so well, it was as though the tailor-artist had known its most intimate measurements; it was “the world as I sensed it,” but whereas I always felt it implicitly and intermittently, there it was before me in the concert hall, something solid, external and directly-perceivable; it gave me the full sense of what it’s like to live wholly in that world. For a while after the concert I was still walking the paths of the campus, dazed and in love, gripped by an exhausting mix of supreme contentment and exhilarating affirmation.

Immediately after the Language Program I tried to capture that experience in a sonnet. But I eventually saw that fourteen lines was not enough space to properly treat it. And so began work on “After a Recital,” the most ambitious poem I had yet undertaken, which I was amending even till late last year when I was preparing my book for publication. It’s the collection’s intellectual centerpiece, containing over 230 lines of unrhymed iambic pentameter. It narrates an evening of inspiring music on a college campus and expands into a contemplation of the power of Romantic art.

The poem begins with the narrator walking home. He pauses to enjoy the peace of the slumbering campus in a warm summer night:

An unillumined meadow

Meeting not distantly the forest wall,

And yonder it, the domes of tree-clad mountains,

Striving into the field of stars, outsweep

From my right hand, as from my left the campus

Spreads an undulating lawn, decored

With purple-headed maples, fountainous willows,

And feath’ry pyramids of fir, each lord

To ’n ample space. White walk-ways curve or arrow

O’er the close-mown green, conveyed by globes

Of glowing white spanned evenly, till reaching

One of wisdom’s several, darkened houses;

They are not dark for this top hour merely:

Gone is the sun-like face of curious youth

As now’s the holiday in mid of year.

But some and I remain these summer days

To pore upon our choicest lores at ease.

It has been clear since the beginning of the poem that the narrator is inspired, and eventually the cause is revealed:

This evening I attended a recital,

And this the cannon of my great propulsion;

That which was sung flung my heart’s portals wide

And stormed its whole capacity, that now,

A sweet and light exhaustion whelms all else[.]

But if from his too-inspired state he feels unable to sufficiently explain the music’s special power over him, he nevertheless decides to try, and we are taken in his memory to the concert hall, which is, for those who have been in it, unmistakably Middlebury College’s Robison Hall at the Mahaney Arts Center:

’Tis sumptuous to see: an ambery warmth

From walls of oak and stone of matching hue

Goes round in prismic aspect, while swart beams

Massively rise at every joint, and rib,

Till its low vertex, ’gainst the conic roof;

Kite-shaped fixtures freeze in flight above,

Bearing, like diaph’nous bowls, clustered

Balls of orange, misty-edgèd light.

After wondering how the music can be conveyed through poetry, the narrator decides to begin by reciting himself the poems the composer used for his pieces:

Come, then; a poet’s proper offering:

Those verses the composer set in tone

That I have brought from foreign tongues to ours[.]

What follows are three internal poems, the very ones Wolf used for his pieces for voice and piano; they are my translations from the original German.

The first is “Secrecy” (“Verborgenheit”) by Eduard Mörike (1804–1875). Starting and ending the piece is the same calm, certain, rhythmically regular music, which mirrors the poem structurally, whose first stanza reappears as the last. This structural adamance of the poem mirrors the insistence with which the speaker argues that it is not any second-hand values that the world might happen to offer which will motivate him, but values of his own intensely-personal choice. And he will cherish the emotions that come from that, be they painful or sweet:

Leave me world, O, it is vain!

Tempt me not with offerings sweet;

But for this my heart does beat:

Its own sweetness, its own pain!

—excerpt from “Secrecy”

The music of the two middle stanzas, which seems to convey the intensity of the pursuit of such values, struggles upward, grandly and emphatically, until, seeming to collapse from the intensity of the climb, it reaches the height, at last.

The next poem, “Even Small Things” (“Auch Kleine Dinge”), is itself a German translation of an anonymously written Italian folksong. The poem presents a little list of physically humble objects (pearls, olives and roses), and considers how even things of small stature can evoke great responses in us. Appropriate to its subject, the music is delicate and unobtrusive, as light and innocent as the sparkle of champagne bubbles:

Even small things can delight us,

Even they beg lofty sum:

Bear in mind the pearl’s petiteness

And how grand the cost for one.

—excerpt from “Even Small Things”

The final poem is “Anacreon’s Rest” (“Anakreons Grab”) by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832). The narrator in the poem comes upon the final resting-place of the ancient Greek poet Anacreon. But rather than a place of melancholy, the grave is bursting with life, covered with lush vines and flowers, loud with the cooing of doves and buzzing of insects:

What grave is before me, which the gods lushly dress

With such animate beauty? ’Tis Anacreon’s rest.

—excerpt from “Anacreon’s Rest”

The narrator contemplates that it is indeed a fitting resting place for a poet whose favored themes of good-natured fun, sensuality, beauty and romance indicate a fair and untroubled disposition, which, though surely acquainted with sadness, believes it so insignificant as to be unworthy of mention:

This fortunate poet enjoyed spring, summer fall,

But was spared of the winter, by the burial knoll.

—excerpt from “Anacreon’s Rest”

Wolf’s music embodies the contemplative mood of the narrator, pausing and musing; it lingers but then decides, sweeping up, assured. But there is a touch of wistfulness. It is as though the narrator of Goethe’s poem felt discomfort in acknowledging a disparity felt between his and Anacreon’s own remarkable, sun-like attitude. But if pain is considered, the music succeeds in its wish to ignore it, and it settles into a still contentment.

After the three pieces have been recited, the narrator then relates the audience’s enthusiastic applause, whose intensity the narrator attributes to a profound response to the Romanticism of these pieces; for Romantic art presents life as it can be and ought to be, which can rejuvenate one’s belief that he can become the hero of his own life. The narrator explains that it is this reminder which propels the audience to its feet as it sends up the ovation, and tells how each listener feels urged to reexamine his values and recommit himself to his highest ones:

The two stood beaming

In our peal of praise, and bowed to eyes

That shone from the sweet sting of soul’s relief;

For we did feel our spirits mercy-tuned,

Resounding with a sort of kind reproof

That came to this, though several each one’s way:

‘That I could learn to quail in Life’s involvements! —

Lose in its workings out this pure conceit:

Life is such a simple, simple thing!

My greatest loves are flowrets o’ the field!

Sweet pinks and mauves, that never could have vexed,

Never vexèd be! It is high wrong

To make a monstrous action of a pinch

That would so eas’ly bring my blisses home!

So far may unchecked fear encroach — no more!

To earn such feeling through grand doings done,

Should have been — will be! — my most constant purpose.

If ’t prove a dream to reach what my whole heart

Has set upon — but no! it has been done!

Might yet be done! This Music proves, it’s true.’

Finally the narrator has reached an intersection of paths. Going left would bring him to his dormitory, and going straight would bring him past the limits of the campus, into the surrounding countryside:

I slowly know – and like a strange idea,

For I’ve stopped like some long-adventured peak

Were won, and all to do now gaze, and gaze –

That leftward I should go, and I should sleep.

Ah, sleep! Though it were welcome to the lid

That weighs, the limb that can bear nothing more,

Could all the soothing darkness it can gather,

And gentle promisings of swevens sweet,

Douse this tall lightning that has dayed the mind?

Or would I trust unto its lethean charms

My heapèd gold? Oh, soon enough must man

Redip the spirit’s chalice – too soon drained! –

At bright Apollo’s spring; let mine as yet

Half-drunk, not be set down, nor let the head

Upon soft pillows lull its pleasing riot

Oversoon!

And so the narrator prolongs his night-time reverie, deciding to continue his walk that takes him into the dark countryside.

Ultimately the tone, form and subject of each of my two Middlebury poems suggested where I should place them in the story-arc I sought to build with the forty-one poems of the book. Although their origin was not directly the reason that they begin and end it, when considering how profound the experiences were that gave rise to these poems, I think it is perhaps not accidental after all that they should each claim such conspicuous positions in the book. Middlebury was a radiant time in my life, and since the book overall expresses (to quote the book description) “a longing and passion for the human soul at its most radiant,” I find it remarkably fitting how Middlebury became both the book’s quiet and alluring opening chords, as well as its grand finale.

Of course, what attending the Language Schools concretely means will be unique to every participant. But I think common behind everyone’s particular experiences in the program is the exciting sensation that hidden possibilities are revealing themselves. Whatever the reason you come to Middlebury to acquire a new language, whatever locked passage there is you wish you could enter, the Language Program places the key into your hand, closes your fingers gently around it, and whispers thrillingly at your ear: “now, open the door.”

To read these poems in full, along with the others in To a Sunbeam and Other Poems, visit Brandon’s website www.brandondumont.com/books to purchase a copy. Readers of the Middlebury Language Schools Blog can use the coupon code MLSSUNBEAM to get 20% off an autographed copy of the paperback version. The offer lasts through December 31, 2023.