The Still-Untold Stories of September 11

| by JM Berger

It’s been 23 years since September 11, 2001. In that time, the public has seen mountains of evidence about the historic terrorist attack, yet many questions still remain unanswered. This week, ProPublica revealed another piece of the puzzle.

Working with lawyers who represent the victims of 9/11 families in a lawsuit against the Saudi government, ProPublica and the New York Times obtained and reported on newly public evidence regarding Omar al-Bayoumi, a Saudi national who has long been the focus of investigators inside and outside government, including the 9/11 Commission. Some of the new evidence was withheld from the Commission, which found that Bayoumi assisted two of the hijackers, helping them rent an apartment and get drivers’ licenses, among other things. The Commission did not allege that Bayoumi had advance knowledge of the 9/11 attack. Investigators and journalists have long pursued a theory that Bayoumi was a Saudi spy, although this has never been conclusively established.

The new evidence, which includes videotapes and phone records, shows that Bayoumi lied to investigators, according to the Times. According to both the Times and ProPublica, the new evidence suggests that Bayoumi’s interactions with al Qaeda operatives and soon-to-be hijackers Nawaf Al-Hazmi and Khalid Al-Mihdhar were part of a much tighter web than his testimony indicated—starting with their first meeting, which Bayoumi told investigators was a chance encounter in a cafe. New video evidence also shows Bayoumi “casing” the Capitol, according to intelligence experts interviewed by both publications.

According to ProPublica, the new evidence “suggest(s) more strongly than ever” that Bayoumi and other people “deliberately assisted the first Qaida hijackers when they arrived in the United States in January 2000.” It’s well worth your time to read both reports, especially the ProPublica piece, which describes the activities of Bayoumi and others in considerable detail.

Through my website, INTELWIRE, I have also published one of the largest collections of primary source material on the 9/11 attacks as a searchable database. Most of the documents can also be accessed and downloaded as PDFs from the Internet Archive, including documents cited by the 9/11 Commission Report and the Commission’s extensive memoranda on its investigation. Today, I am publishing a 1,966-page PDF of Awlaki’s FBI files obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, which is also searchable in the 9/11 database.

I want to talk briefly about another long-simmering aspect of this case—Bayoumi’s relationship to American al Qaeda ideologue Anwar Awlaki. I’ve written about this before, most extensively for The Atlantic in 2011. (Document links in that story are dead, but all of the documents are available in the database above or here.)

Awlaki was an American citizen who earned a wide mainstream following among English-speaking Muslims before fleeing the United States in Year after investigators began to probe his links to 9/11. Years later, he eventually revealed himself as a member of al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. He was killed in 2011, in an unprecedented U.S. drone attack targeting an American citizen. To this day, it’s not clear exactly when and how Awlaki became associated with al Qaeda, but his links to the hijackers raise serious questions that are only emphasized by the new evidence.

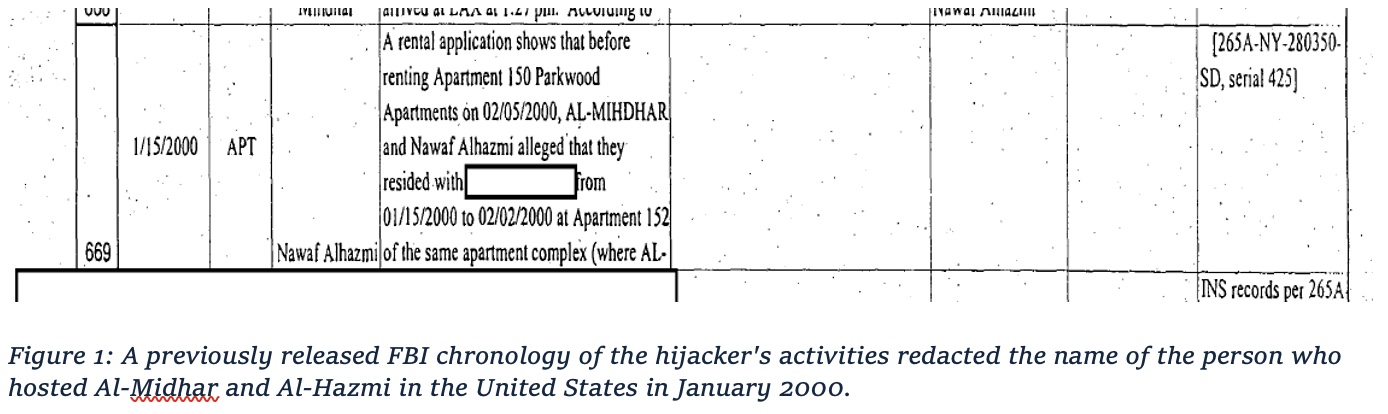

Al-Hazmi and Al-Mihdhar arrived in the U.S. on January 15, 2000, flying into the Los Angeles International Airport. The 9/11 Commission report and FBI FOIA files withheld information about where they spent their first two weeks in the country. The next known event on their itinerary was February 1, 2000, when they met Bayoumi in the café—a meeting that looks increasingly likely to have been planned rather than random. The new evidence shows that Bayoumi lied about the timing of the trip.

The hijackers had relocated in San Diego no later than February 4 and rented an apartment on February 5. According to ProPublica, the new evidence shows that “Awlaki appears to have met Al-Hazmi and Al-Mihdhar as soon as they arrived in San Diego.” Awlaki was an imam at a San Diego mosque at the time. He and Bayoumi were well-acquainted, and Awlaki became acquainted with the hijackers as well, offering them spiritual guidance and perhaps material support while they were in San Francisco.

In 1999, the FBI had begun investigating Awlaki on suspicion of involvement with Hamas. The investigation concluded in March 2000—at least a month after the hijackers had arrived in San Diego and made contact with him. Records of the Hamas investigation were almost entirely redacted from the FOIA records I obtained in 2012.

Awlaki left San Diego later in summer of 2000, traveling first to Yemen and then taking up residence as imam of a Virginia mosque in early 2001. Fourteen months after first meeting Awlaki, Al-Hazmi and Al-Mihdhar showed up once again on his doorstep, this time in Virginia, where they received yet more assistance and spiritual guidance. The available evidence strongly suggests they had crossed the country specifically to seek him out after completing flight training in Arizona.

Eerily, Awlaki was sitting in an airplane bound for Washington, D.C., as the September 11 attacks unfolded. As I wrote in my 2011 book, Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go to War in the Name of Islam:

The Yemeni-American imam was returning home from a conference in San Diego, the city where he had first befriended two of the men who were even now helping Hanjour complete his suicide mission. A third hijacker on Flight 77 had also met Awlaki, later, at the Dar Al Hijrah Mosque near Washington, where the imam now worked.

Awlaki was landing at Reagan National Airport around the time that the hijackers were boarding their flight at the nearby Washington Dulles International Airport. The timing was extraordinarily tight. Awlaki heard news of the hijackings during his cab ride home.

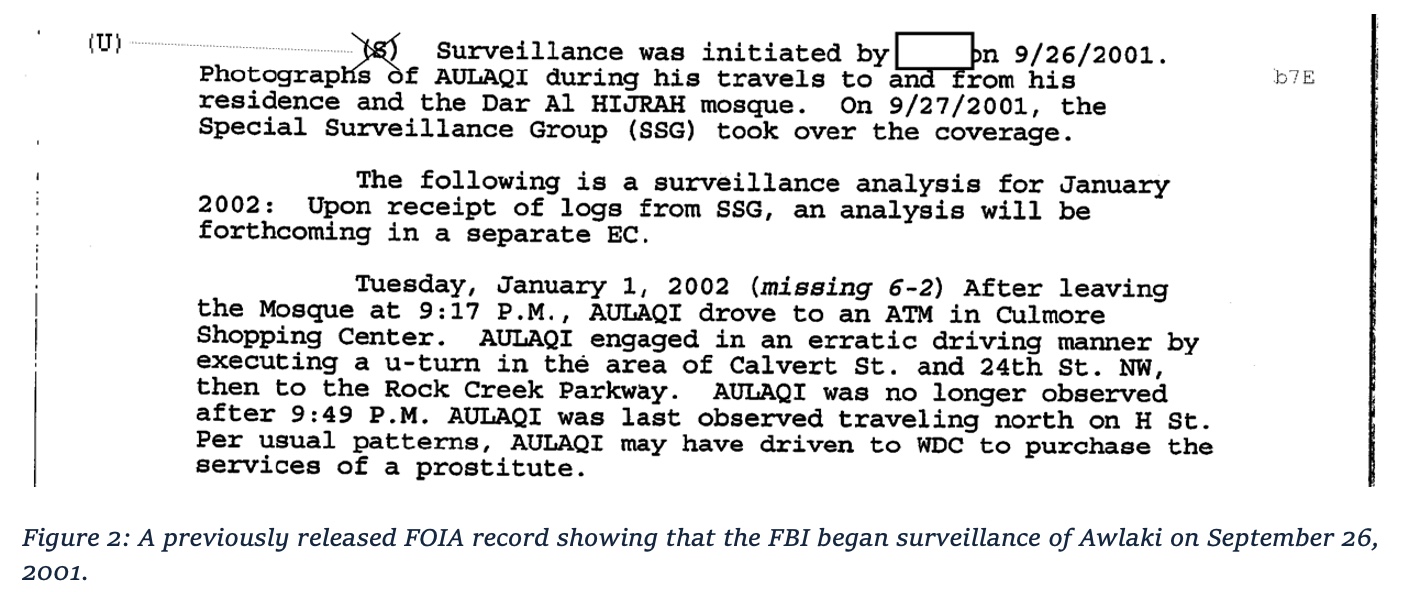

Before the end of the month, Awlaki was assigned an FBI surveillance team, which followed him around the region. On some occasions, they witnessed him patronizing prostitutes. On multiple occasions, he used evasive and aggressive driving techniques to throw off his pursuers, sometimes running red lights to shake the tail.

The face Awlaki presented to the general public prior to September 11 had been one of moderation. In the wake of the attacks, his sermons and conversations became more and more overtly dark and radical, a descent that would continue for years. Was he truly radicalizing, or was the façade simply slipping? It’s hard to be certain, but the evidence increasingly suggests the latter.

In 2011, I wrote, “Ten years after September 11, the case against Anwar al-Awlaki remains unsolved, but it can hardly be considered closed.” Unfortunately, that statement is still true. Questions about Awlaki’s role in the September 11 attacks may never be fully resolved, but the latest New York Times and ProPublica reports hold out hope that more evidence may yet emerge. Awlaki, “as American as apple pie,” was one of the most important figures in modern extremism. We deserve to know everything.