Climate Change Is Mostly a Human Problem, Not a Technological One

| by Jason Scorse

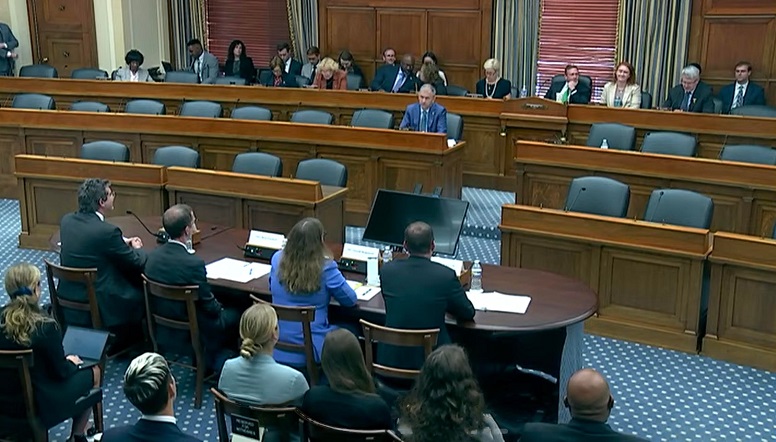

Tackling climate change right now is less about science and technology, and more about people, politics and behavior change, environmental policy Professor Jason Scorse told Foreign Affairs in a recent Q&A.