Dangerous Organizations and Bad Actors: National Action

| by CTEC

Introduction

National Action was a neofascist, militant accelerationist terrorist organization active in the United Kingdom from 2013 until its proscription in 2017, being the first far-right group to be banned in the U.K. since the Second World War. Established by Alex Davies and Benjamin Raymond, National Action was the first group to develop an offline presence from the Iron March web forum and grew into a model for other accelerationist, fascist organizations to emulate in their infancy. In its four years of public activity, National Action engaged in online harassment, stickering campaigns, and antisemitic and Islamophobic street demonstrations. It publicly celebrated the murder of Member of Parliament Jo Cox by far-right activist Thomas Mair, who has no known organizational ties to the group. This, along with subsequent death threats made to a number of other left-wing MPs, was instrumental in their proscription. Following their banning, some leaders sought to continue National Action through a clandestine network of devoted members and continued to meet in secret through 2017, but enforcement led to a steep decline in organization membership and the conviction of several prominent figures of the group.

Ideology

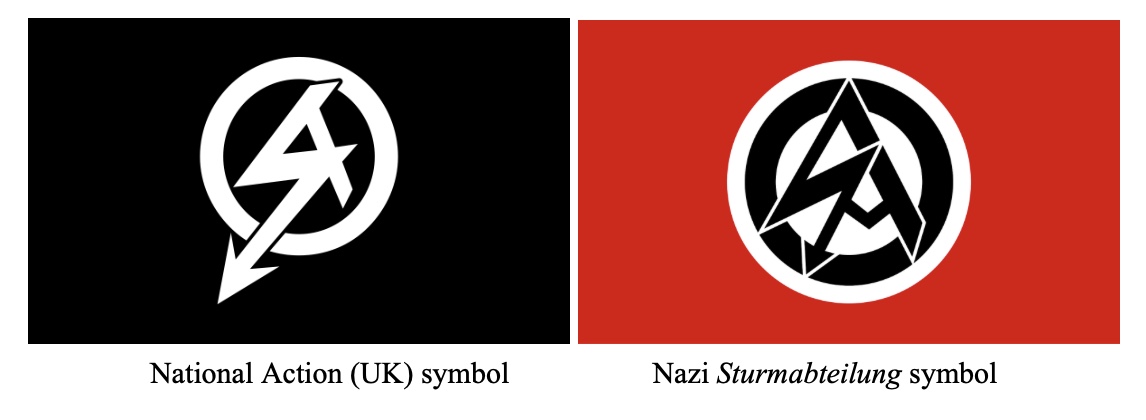

The group’s founders first organized their conception of National Action on the Iron March forum, an important ideological breeding ground for militant accelerationist groups. National Action was founded in part as a response to other far-right groups in the United Kingdom, especially the British National Party (BNP), drifting towards electoral politics and more socially palatable rhetoric in the 2000s. Skeptical of the BNP’s moderate shift, National Action’s founding members envisioned a youth-oriented, “white jihadist” movement that embraced overt racism and militancy. They idolized Nazism, international fascist groups, and the legacy of British fascist Oswald Mosely and his British Union of Fascists (BUF) party. The group’s insignia was itself modeled after that of the Nazi Sturmabteilung, the original paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. Seeking to cultivate a broad, pan-European perspective and network, National Action derived ideological inspiration from fascist movements both contemporary and historical, such as José Antonio Primo de Rivera of the Spanish Falange, the Jobbik party of Hungary, Adolf Hitler, Corneliu Codreanu and his Romanian Iron Guard, and the fascistic metaphysics of Julius Evola.

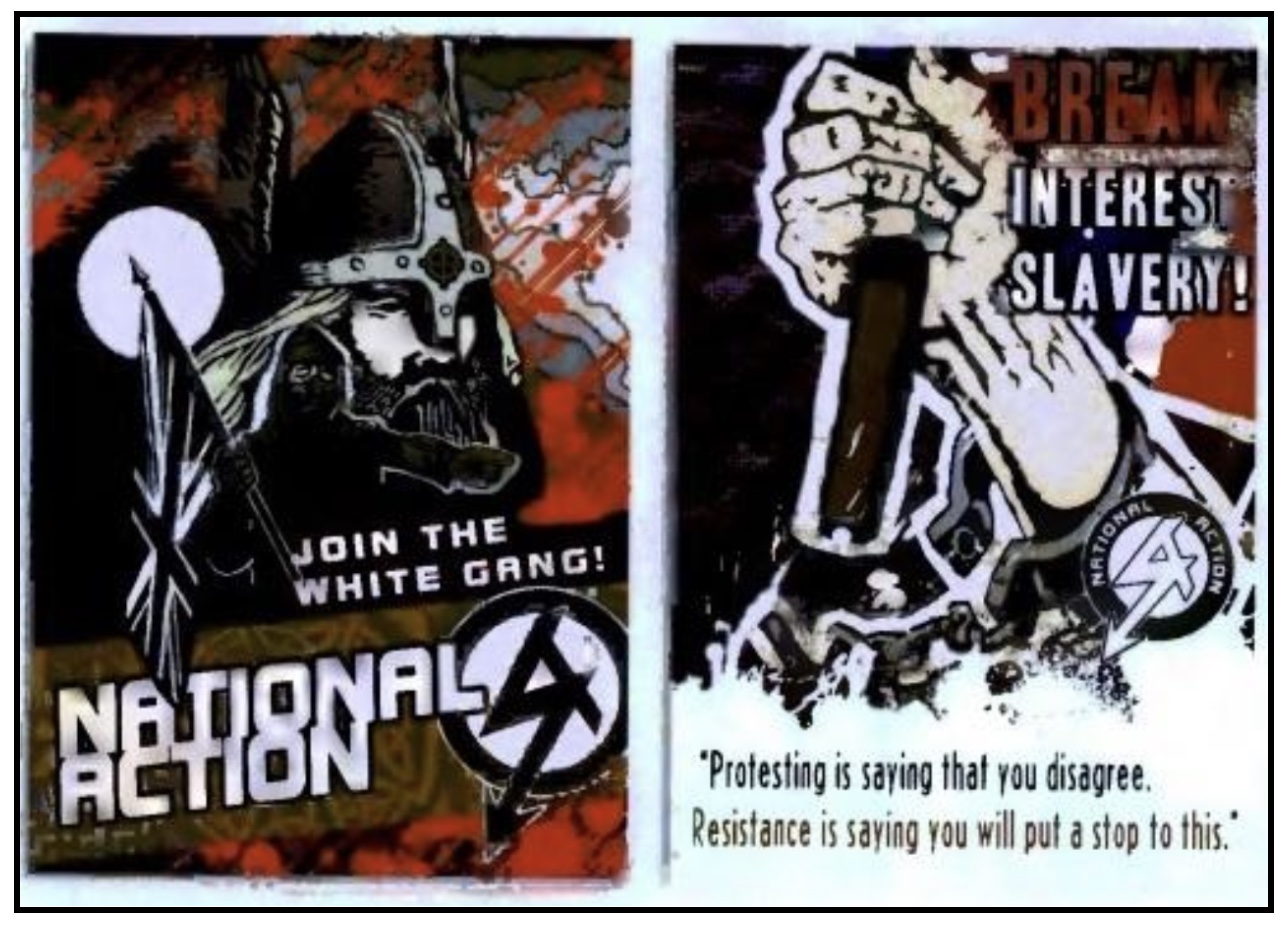

National Action’s identity as an independent entity within the splintered British fascist space was vital to their ideology and strategy, distinguishing themselves from other fascist organizations through their eschewing of the traditional fascistic framework of protecting women and children in favor of violent misogyny, and their prioritization of recruiting “moral men” of action over what they considered to be ineffectual intellectuals. Provocative demonstrations attracted media attention and empowered the “masculine, aggressive” movement. The skull mask style commonly used by neofascist militant accelerationist groups became a key piece of the group’s recruiting and identity. Its leaders believed they could attract British youth by cultivating a fascist subculture and aesthetic that would inspire both external respect and internal pride for organization members.

Despite their public activities, National Action’s leadership did not seek to mobilize the public to achieve their goals as they expressed doubts that National Action’s ideology would ever garner enough appeal to take power under normal circumstances. Instead, they felt the organization could position itself and its ideals as a social presence that would “blossom in a time of crisis,” believing that the organization was merely a vital first step for furthering fascist ideology in the British Isles. Accordingly, the group’s actions, such as their propaganda dissemination and street demonstrations, were not designed to advocate for their cause through rhetoric and argument, but rather to lay out a blueprint designed to spur already-radicalized sympathizers into action against society.

Membership

Alex Davies and Benjamin Raymond founded National Action in 2013. Davies had left the youth wing of the BNP due to frustration with the organization’s lack of militancy and prioritization of winning electoral seats, and subsequently became National Action’s primary recruiter. Raymond, an administrator on Iron March who became National Action’s propagandist, produced most of the strategy and propaganda material published by the group. After National Action was banned, Davies founded the nearly-identical National Socialist Anti-Capitalist Action (NS-131). In 2016, Christopher Lythgoe rose from a regional leadership position to become the new head of National Action. The group’s proscription later that year did not seem to concern Lythgoe, who told members “We’re just shedding one skin for another,” while the people, bonds, and ideas of the group would continue underground. Other prominent figures included Alex Deakin, Garron Helm, Ashley Bell, Jack Renshaw, and Ryan Fleming, who was likely the group’s link to the Order of Nine Angles.

National Action likely included about 50-100 active members at its peak, though they took precautions about sharing information that made prosecution and accurate membership estimates challenging. Targeting primarily males between the ages of 16 and 25, National Action organized its members into a decentralized network of regional chapters around the United Kingdom. Members met often with these regional leaders in pubs and other informal settings to discuss ideology and organization. They were encouraged to maintain a high level of physical fitness, and many participated in martial arts training coordinated through the organization itself..

Affiliations

National Action’s development through the Iron March forum provided the group with an elaborate network of ideologically-aligned groups and contacts from around the world. Its early success provided a roadmap for other fascist organizations to follow in other countries. Other Iron March members worked with National Action members through the forum to understand successful organizational strategies and coordinate accelerationist ideology. Ultimately, those individuals went on to found entities like the Atomwaffen Division in the United States, Antipodean Resistance in Australia, and Skydas in Lithuania.

Iron March allowed National Action activists to develop international relationships and network with established fascist movements, such as Golden Dawn in Greece, CasaPound in Italy, and the Nordic Resistance Movement in Scandinavia. The group built particularly strong relationships with neo-Nazi Polish nationalist group National Rebirth of Poland, with this collaboration continuing through National Action’s successor organizations following their proscription. National Action members even traveled to meet with the Nordic Resistance movement in Finland, Azov in Ukraine (pre-Russian invasion), and other far-right groups operating in Germany, France, Estonia, and Latvia.

Outdoor physical training sessions occurred periodically with other fascist organizations. In 2014, some National Action members attended a camp in Wales with the Odinist physical training group Sigurd Legion, Russian neo-Nazi mixed martial arts organization White Rex, and the Western Spring blog. Western Spring described the camp as an opportunity for nationalists to network and embrace pagan spiritual heritage and white pride.

Through Ryan Fleming, a regional organizer for National Action, the organization appeared to be infiltrated and influenced into Left-hand path, occult-oriented neo-Nazism by the Order of Nine Angles (O9A) and their Tempel ov Blood (ToB) corollary. Fleming was alleged to be an active promoter of O9A on the Iron March forum and part of the O9A affiliate Drakon Covenant in Yorkshire. The Drakon Covenant was linked to National Action, but the extent to which O9A influenced the organization is less clear than with other groups arising from Iron March, such as Atomwaffen Division. However, police raids on some National Action members’ homes uncovered evidence with O9A symbols, suggesting that Fleming’s occult approach reached at least some parts of the group.

After National Action was banned, some members continued meeting and training in secret. Group leaders also created several successor groups including NS-131, Scottish Dawn, and the System Resistance Network (SRN) to evade the ban. SRN struggled with infighting over how much O9A-affiliated occultism should feature in the group’s ideology. In 2018, this led to SRN member Andrew Dymock founding Sonnenkrieg Division, a UK-based group heavily inspired by Atomwaffen Division and O9A. The British government later added all of these to the proscribed organizations list.

Propaganda

National Action’s propaganda efforts sought to galvanize sympathetic audiences towards direct action through the promotion of ideas over specific organizations. Branding was centrally important to its leaders, and the movement adopted an all-black aesthetic style for street demonstrations often paired with sunglasses or a skull mask—a symbol that became characteristic of the neofascist militant accelerationist groups emerging from Iron March. In 2014, National Action’s homepage stated that traditional propaganda would reach only “softcore do-nothings,” while National Action intended to reach only “hardcore activists.” Overall their propaganda featured rampant and extreme misogyny, racism, homophobia, and Islamophobia, and especially antisemitism.

Arrests/Plots/Attacks

Following National Action’s proscription in 2018, a surge in investigations into the group produced eleven arrests, with sporadic high-profile arrests taking place over the ensuing years for either membership within or fundraising for the terrorist organization.

National Action initially gained notoriety in October for a Twitter-based trolling campaign against the Jewish Labour MP Luciana Berger. Member Garron Helm posted a photoshopped tweet of Berger with a Star of David and the hashtag #HitlerWasRight. After Helm was convicted and sentenced for the tweet, Berger received more than 2,500 hate tweets and police arrested a group of National Action activists who planned to demonstrate outside her office.

In January of 2015, National Action member Zack Davies attempted to murder Dr. Sarandev Bhambra Sandip, a Sikh dentist, with a machete and hammer. While Raymond claimed not to know of him, Davies said he was a member of National Action and had been active in online spaces frequented by group members. Davies was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Inspired by O9A ideology, Ryan Fleming amassed a series of convictions for sexually assaulting minors. As purported in some O9A texts and teachings, the sexual abuse of minors is a desirable way for adherents to challenge common societal taboos, something that the philosophy dictates holds humans back from reaching “enlightenment.” Fleming’s convictions included one from 2011 when he imprisoned, tortured, and forced a minor boy to commit sexual acts and another from 2017 when he was convicted of sexually abusing a 14-year-old girl. He was sentenced to another six months in prison in 2021 after police found he was messaging young teenagers online in violation of the sexual harm prevention order against him.

Jack Renshaw was sentenced in 2019 to at least 20 years in prison for planning to murder Labour MP Rosie Cooper. Renshaw’s plot was inspired by the murder of MP Jo Cox, committed by far-right extremist Thomas Mair who is unconnected to National Action. An avid spokesperson for National Action, Renshaw had purchased a machete and contacted National Action members including Lythgoe about his plan. Lythgoe allegedly suggested Renshaw target Home Secretary Amber Rudd instead, telling him “Don’t fuck it up” and another National Action member recommended he target a synagogue. Robbie Mullen, a disillusioned National Action member, had been working as an informant for Hope Not Hate, which tipped off both police and Cooper. The would-be attacker was arrested before he could attempt the assassination.

Trials of members after the organization was banned revealed that several members had informational or physical materials for creating homemade explosives. Along with his conviction for membership in a banned organization, Raymond was found guilty of possessing materials that included Anders Breivik’s manifesto and a guide to crafting homemade detonators. Lythgoe was also convicted of being a member of National Action, but was found not guilty of encouraging the planned murder of Rosie Cooper. National Action member Jack Coulson, then 17, was convicted of making a pipe bomb and for downloading a handbook on how to make weapons and explosives. Raymond and Davies were arrested and convicted in 2021 and 2022, respectively, for continuing membership in National Action after its proscription.

Conclusion

National Action was a seminal early militant accelerationism entity. Largely defined by its demonstrations that brought the group from an online network to an offline organization in 2014, it maintained a strong online presence and mobilized social media-based hate more effectively than any other group active at the time. National Action helped pioneer a new era of social media-based mobilization among far-right groups, using Twitter and other platforms to mobilize thousands in hate campaigns against public figures. As social media exploded in popularity during the organization’s zenith, these online attacks became an essential part of militant accelerationist tactics at that time.

Despite the British government banning National Action, the organization had already become an effective blueprint for militant and accelerationist far-right groups looking to move from online to offline action. Their aesthetics, organizing principles, messaging, and outreach model proved innovative and effective within the nascent online militant accelerationist community at the time. However, the group’s proscription led to a rapid decline in membership and a series of significant convictions against the group’s leaders, but successor organizations and fellow travelers around the world learned from the networked, street-oriented design of National Action and reproduced it to form other skull mask groups.

While National Action professed a commitment to action, violent attacks linked to the group were often undertaken by lone actors, at times with endorsements or encouragements from leaders and other members. The secretive nature of the organization obscured the extent to which National Action directly engaged in command and control functionality of members’ violent acts, but the militant accelerationist themes of its ideology, connections to other violent fascist groups, and evidence uncovered in police raids suggest more lone actor attacks were planned before the group’s decline. National Action failed to build a clandestine operation after it was banned, but its effectiveness at spreading fascist ideology on and offline inspired former members and others to carry on its legacy in new far-right groups and as and lone wolves in the years that followed.