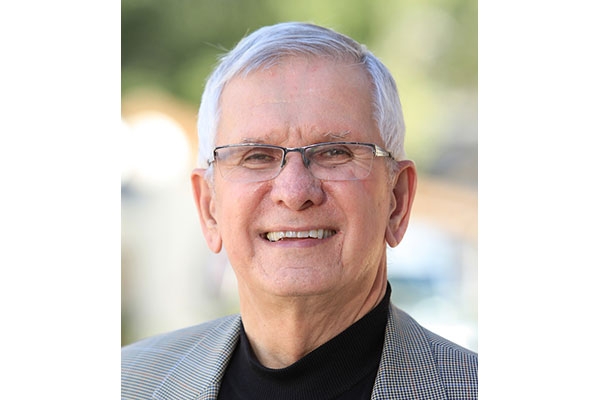

Professor Ed Laurance Reflects on 25 Years at the Institute

Professor Ed Laurance joined the faculty of the Monterey Institute in 1992, moving over from the nearby Naval Postgraduate School (NPS). Earlier in life, he graduated from West Point in 1960 and then served in the U.S. Army for a decade, including service in combat in Vietnam. After his discharge, he earned a master’s degree in International Relations and Public Administration from Temple University and a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania. The first-hand knowledge he gained about weapons of war during his military service became a special focus of his academic research, leading to groundbreaking work with the United Nations and a wide range of international NGOs on small arms control. During his 25 years on the Institute faculty—interrupted only by three years serving as dean of the Institute’s Graduate School of International Policy Studies (2006-2009)—Laurance saw both his daughter (Paddy Laurance MATESOL ’94) and stepdaughter (Anna McCloskey MAIEM ’14) graduate from the school where he taught. He will retire at the end of the month after serving as the faculty speaker at Winter Commencement on December 14. We sat down with Professor Laurance recently for a look back at his distinguished career.

Tell us about your military service and how it shaped your academic interests at the Naval Postgraduate School and then here at the Institute.

I graduated from West Point in 1960, and I left the Army in 1970. I served in Germany, Texas, and Vietnam, and I finished up at the height of the Vietnam War in North Philadelphia, teaching ROTC at Temple University. I soon discovered that the America I had left in 1966 had changed. The whole campus was on fire, and the leaders of the antiwar movement there were all the former soldiers — they were saying “This is what’s happening, this is what we were doing, I was there.” They were the witnesses, and they had credibility. And they left all of us alone who were wearing our uniforms on campus in the midst of all these rallies. It was an amazing time, and those experiences, plus the influence of my family, really hastened my conversion from warrior to peacebuilder, or whatever I call myself now.

I specialized in the international arms trade at NPS. When I was retiring from NPS after 20 years, I talked with Steve Baker [then dean of the Institute’s Graduate School of International Policy Studies (GSIPS)] about joining the faculty at MIIS, I told him that the arms control work I’d been doing at NPS was in my past. When I came to MIIS full time in 1992, I figured that was the end of it, but I always tell my students that doors will always open that you don’t expect. My life story is one of always walking through these doors. I have no regrets.

I arrived here just as the Cold War was ending and suddenly there was a veritable explosion of illicit arms trafficking because many countries, the U.S. included, had a surplus of small arms and firearms, because it appeared for a while like we weren’t going to fight any conventional wars anymore. So the surplus arms were being sent abroad into all these internal fights within states.

Then I got a call in December of 1992 from a friend I had worked with in the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in the 1970s, who asked – based on the book on the arms trade that I had just published — if I would be interested in being a consultant to develop an international arms register. That started everything – 25 years of work on conventional arms control with the UN and various NGOs, and coming to MIIS made all that happen.

I worked with the UN on the arms register initiative through 1994 and then I was selected to be a consultant to a panel of governmental experts from 22 countries, which positioned me to become the expert on small arms control. Starting in 1995 I worked for the panel for a year and one of our recommendations was for a global conference on small arms, which happened in 2000-2001; there were four sessions and we traveled all over the world getting feedback from governments and people about what we should do about solving this problem. As the consultant to that conference, I wrote the draft of the Program of Action on small arms, a landmark guide to future action.

Do you feel like your military service and combat experience gave you added credibility when addressing these issues?

I do. During this period I was essentially campaigning for the arms register and Program of Action, and I gave many speeches. I would close by saying that “you have to remember that these weapons were manufactured for legitimate military purposes… I know all these weapons, I fired them in anger. But the problem is that they’re now in the hands of people who shouldn’t have them, and those people are killing women and children. Our goal is to do something about that.” I think my military experience gave me a lot of credibility, particularly in the NGO world, and helped me to become a leader in this whole campaign.

The book I’m working on, a memoir, will have “From Warrior to Peacebuilder” or something like that as part of the title. The opening of the book will be me on the bayonet range at West Point at 17, sticking a bayonet into the dummy and yelling and screaming. They wanted to make me into a warrior, and they succeeded. I think the fact that I had been in combat really influenced my entire professional life and put my focus on the guns rather than the root causes of armed violence, because I know firsthand about these weapons and the damage they can do.

What’s the biggest milestone that’s come out of all the work you’ve done with the UN and various NGOs on small arms?

I would have to say the Program of Action. It was the first international consensus agreement on what the norms should be to control small arms, and the first time the world started using the phrasing “states should” – as in, states should make sure that arms exports go only to the intended recipient, or states should prevent the illicit manufacture of arms. It was a landmark in that respect, and it’s still around – I’ll be taking some students there in the spring for the review conference, which happens every six years.

And then there was my 15 minutes of fame. At the time that the first conference on small arms was starting to take shape in 1997, the landmine campaign was in full swing. I had been working for the government of Canada as a consultant and the foreign minister of Canada had invited me to make a presentation on the last day of the landmine conference on how we now move the landmine coalition forward to tackle a bigger problem: the proliferation and misuse of small arms and light weapons. I was on TV with the foreign minister that night!

With Canada’s help, I along with my former student Bill Godnick MAIPS ’97 founded what became the International Action Network on Small Arms, with over 800 NGOs. It was very influential in convincing governments to sign on to the UN Program of Action on small arms, as well as in promoting the Arms Trade Treaty.

Are there other projects you worked on that carry special meaning for you?

Yes. At one point I developed a hand grenade buyback program for the United Nations to implement in El Salvador — that came out of a student project that I had developed here at MIIS. And then in the summer 2005, after Hurricane Katrina, my parish raised $250,000 for hurricane relief and asked me to figure out what to do with it. Four of my students stepped up and helped raise another $750,000 from Catholic Charities — using their notes from their weekend workshop on grant-making — and then designed a program rebuilding 17 homes in a year. It was another example of using the skills we teach on real-world programs.

How has your approach to teaching evolved over the 25 years you’ve been at the Institute?

At the Naval Postgraduate School I was a lecturer on academic topics – lectures, quizzes, midterm, final. I was not very involved with the students beyond that. Very early on at MIIS, I saw the difference here – I could actually have an influence on students’ career paths. It became my favorite aspect of my time here.

By 2001, I was working with many young people from other colleges and universities. They constantly commented that their schools (Princeton, Harvard, etc.) weren’t teaching the skills we did at MIIS. I began to see that our graduates really were better prepared than other young people who, even if they graduated from a top school, didn’t know how to actually do anything when they hit the ground.

One of the things that happened during this period is I put in for a grant for a program to teach our students the skills needed to actually do things on the ground. I never heard anything, so I moved on, and then all of a sudden the money came in – $200,000! I was awake for three straight nights saying “What have I done? I can’t possibly do this.” Finally I went to Beryl Levinger and said “Here’s the situation… I don’t really have any choice but to send the money back.” Her quick response was “You never send the money back!” That was the birth of DPMI (Design, Partnering, Management, and Innovation), which Beryl has made into a world-class program that showcases the Institute’s immersive learning approach.

As I came to realize that what the students wanted was to know how to do all these things on the ground — how to design a program, how to monitor it and so on — I began teaching a course in program evaluation that Beryl and I worked together to develop. In the last few years the course has focused more and more on taking students out into the field to do actual program evaluations. I’ve taken a group to Chicago to evaluate a violence reduction program, and for two semesters I along with Carrie Mann MAIEP ’98 took students to the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Sacramento. We just recently received word that IRC headquarters in New York called the work we did with them the best student-led project they’d ever seen.

I’m very proud of the fact that all of my work with the UN was fully integrated into my courses on Security and Development, Global Governance and International Organizations.

How did these steps in your evolution as a teacher play into the creation of the International Professional Service Semester (IPSS)?

In 2002 the Institute as a whole was still very classroom oriented, so that’s when I proposed the idea that became the International Professional Service Semester. It took a year to get the program launched, partly because my faculty colleagues would say “I just don’t understand this. Are you telling me that a student would get more out of working in Geneva for six months than taking my course?” The answer, of course, was “Yes!”

The first year, three students volunteered for it, and I managed it all myself. I was traveling a lot with my UN work, and If I was in Geneva, I would just go to various UN offices and talk to people and line up internship opportunities. The next year, in 2003, we had 25 people go on IPSS.

I always tell my students that doors will always open that you don’t expect. My life story is one of always walking through these doors.

How did your time as dean come about and what do you remember most about that time?

It was a strange situation, where GSIPS had just had a failed search and then I was encouraged to take the position. I was advised in essence to “just make the trains run on time for a couple of years,” until the merge with Middlebury was complete, but I did manage to get some things done. The first was to set up the first January term program that actually put students on the ground working — Team El Salvador. That’s changed now – there are many such J-Term programs – but I’m proud of having played a significant role in immersive learning becoming part of the Institute’s mantra and identity. A lot of the momentum for that idea seemed to grow out of IPSS and then Team El Salvador.

Being dean of GSIPS was a hard job; it was a huge number of faculty meetings and they were very contentious, because the school was in transition. My favorite part of it was motivating incoming students — I still have all of my opening speeches to the new students.

You also served as the Institute’s coordinator of veterans affairs for several years.

Yes. A student veteran named Marcos Medina MAIPS ’12 approached me because I was the only veteran on the faculty. After talking with Marcos and the administration, I was named the faculty advisor for the veterans. I had lots of conversations and get-togethers with them and it absolutely delighted me, because whatever they did before, when these veterans arrive at MIIS they arrive as mature students. In that sense they’re like Returned Peace Corps Volunteers.

For me personally, working with student veterans is the first time I experienced people talking openly about having PTSD [Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder]. In my generation, hardly anybody would admit it. Everyone knew it existed, but everybody who had PTSD was in the closet. Along with Students Services, I worked a lot with some of these veterans and found it really rewarding.

I think the life experience these veterans bring increases the level of maturity in the classrooms in which they are active. I think if you asked the other students on campus what they think about veterans the response would be very positive, and I think many veterans feel like they also benefit from mixing with non-military people.

What do you think makes Institute faculty and staff unique?

One of the best things about working here has been the staff. As a faculty member I’ve gotten to know a lot of staff and these people work their tails off and they’re very loyal to the Institute. It’s an academic institution, but staff have an important role to play and I think they do it extremely well. The three years I spent part-time at the Center for Advising and Career Services were three of my happiest.

What are you going to miss most about working at the Institute?

This place is really unusual. I have academic colleagues all over the world, but I don’t know many who mentor students, teach them, encourage them, help them get good internships, and then work with them as colleagues after graduation. Three weeks ago on my new UN assignment – building a curriculum on small arms control — I needed some help from people who are now doing this work and I called on three of my former students [Heather Sutton MPA ’12, Rachel Stohl MAIPS ’97, and Bill Godnick MAIPS ’97] to serve on a panel with me. There are many others out there.

The idea that students I’m working with in the classroom are going to go out and become my professional colleagues — that’s what I’m going to miss the most. I’ll miss that experience of preparing students to be change agents. They really do go out and make a difference – it’s not just a slogan we have here.

For More Information

Jason Warburg

jwarburg@middlebury.edu

831-647-3516

Eva Gudbergsdottir

evag@middlebury.edu

831-647-6606