Translation Professor Helps Bring “Lost” 17th Century Italian Operas to the Stage

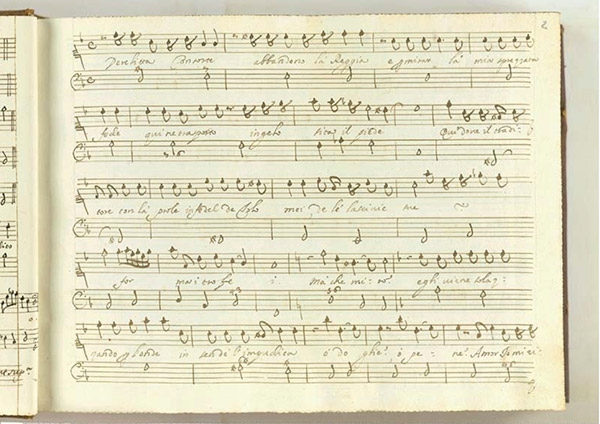

It sounds like the pitch for a Dan Brown novel: intrepid young investigator comes across 350-year-old documents gathering dust in Venetian archives and calls on graduate school professor for help unlocking their true meaning. But that’s more or less exactly what happened when French-Italian mezzo-soprano Céline Ricci, the founder/director of San Francisco opera company Ars Minerva, contacted Middlebury Institute translation professor Joe McClinton for help after finding a trove of “lost” operas in the archives of Venice’s Biblioteca Marciana.

“These have been exciting opportunities to apply translation in helping to revive ‘lost’ masterpieces,” says McClinton, a self-described “opera geek” since he was a freshman in high school checking opera records out of the local library in Pennsylvania. In the intervening years, he mastered German, Italian, and French out of a love for opera and had aspirations to become a conductor before he figured out that the highly competitive scene was not for him.

Productions of the first two of these long-lost operas, Daniele da Castrovillari’s La Cleopatra and Carlo Pallavicino’s The Amazons in the Fortunate Isles, debuted in San Francisco in 2015 and 2016. The last known productions of each had been mounted in 1662 and 1679, respectively, during the infancy of Venice’s rich opera tradition.

McClinton’s work on La Cleopatra began by translating the opera from the old Italian into English to help the performers better understand the complexities of the plots. The next stage involved fine-tuning the translation for a modern audience, which meant some rewording to add lyricism and emotion. McClinton sat in on rehearsals to match his translation to the performances and ensure the essence of the plot would be understood.

Both productions were met with rave reviews, and McClinton is currently working with Ars Minerva on its production of a third “lost” opera, La Circe, which dates from 1665. McClinton describes it as “a story of what happens back at the ranch after Ulysses escapes from Circe’s clutches.” The music is by Pietro Andrea Ziani (1616-1684), with libretto by Cristoforo Ivanovich (1620-1689).

“Translation plays a role not just in communicating with the audience,” explains McClinton, “but in actually building the production. Most of the singers aren’t fluent enough in 17th century Italian to understand everything their character sings, so well in advance of rehearsals I prepare a full ‘literal’ translation to let them know exactly what their words mean.”

During the rehearsal process, McClinton “ruthlessly” prunes and rephrases the original translation to build the supertitles that are projected above the stage and fit them to the action they describe. “The idea at that point is to reduce the words down to the most instantly communicative message possible.” He adds that a sort of “feedback loop” develops where the performers help to refine the titles while the titles help to inform their performances.

It’s the intersection of lifelong passions for McClinton, whose talent for facilitating communication through translation has brought him full circle, back around to the world of opera that first captivated him in high school.

For More Information

Jason Warburg

jwarburg@middlebury.edu

831.647.3156

Eva Gudbergsdottir

eva@middlebury.edu

831.647.6606