The Economic Value of America's Estuaries

Estuaries have always been an essential feature of the economy. “The Economic Value of America’s Estuaries,” written by the Center for the Blue Economy and TBD Economics LLC for the non-profit organization Restore America’s Estuaries, details the surprisingly huge contribution of these areas to the U.S. economy, and fills in a critical gap for coastal managers and policy makers: the economic benefit of natural infrastructure and blue carbon sequestration.

Even before European colonization,Native Americans lived either permanently or seasonally in estuary regions in large part because of food supply. European colonization, and the population and economic growth following it, were centered in the estuary regions where North America could most easily connect with Europe. That history established a pattern of economic importance which continues to today. The counties in the estuary regions of the continental U.S. comprise 4% of the land area, but 47% of economic output, and 38% of employment, population, and housing. Eight of the ten largest metropolitan areas are located in estuary regions.

Estuaries are geographically small and economically huge.

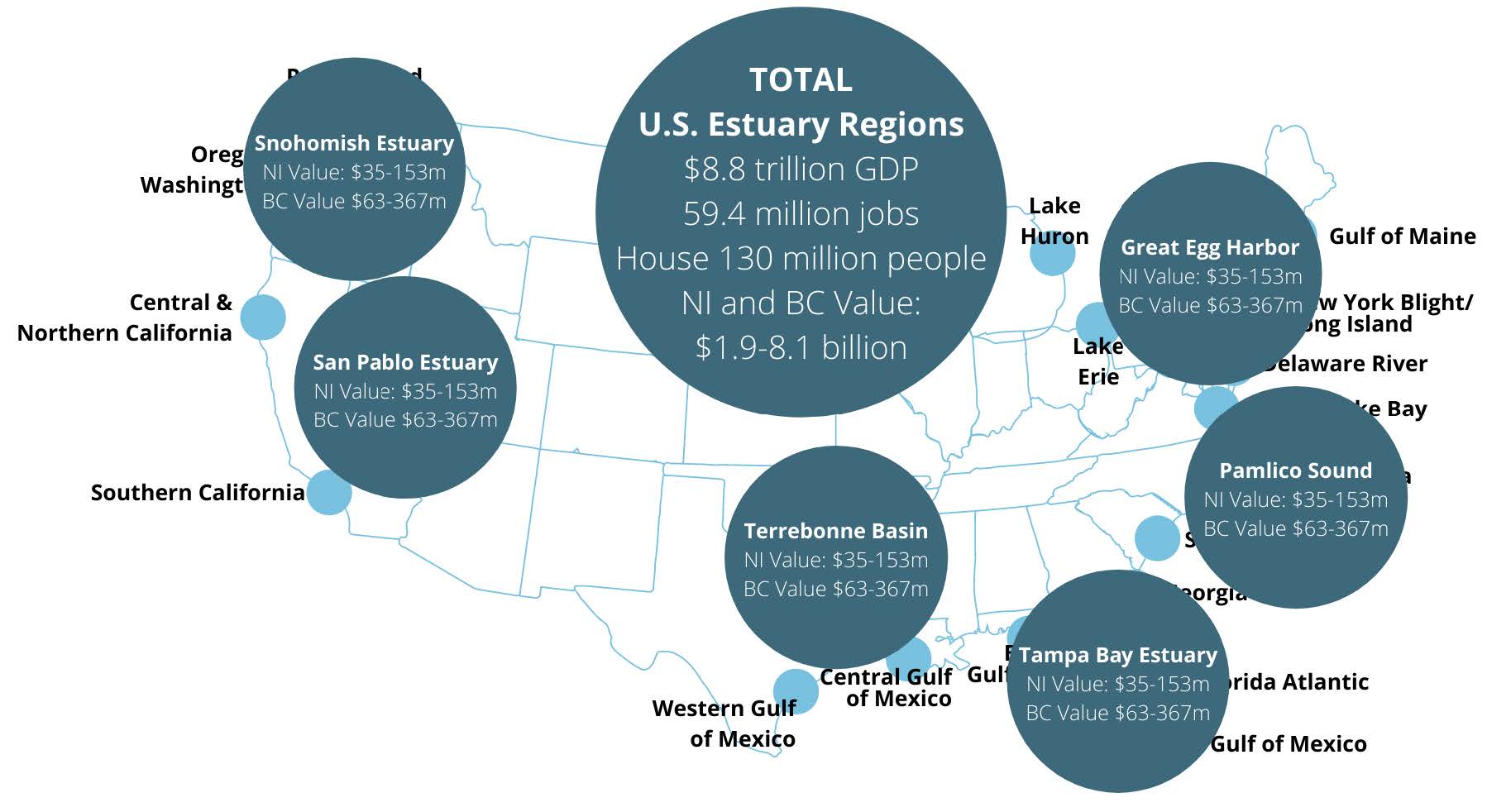

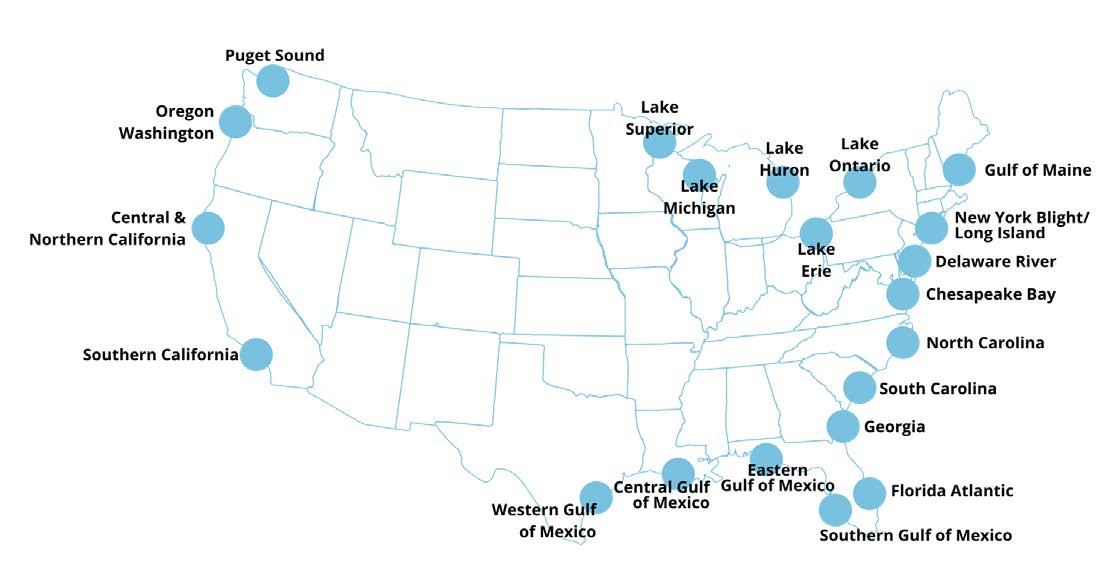

The report is divided into two main study areas: A broad regional study, which includes twenty-one regions comprised of 380 counties bordering the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, the Pacific, and the Great Lakes, and six case studies for the assessment of two crucial climate change related services: natural infrastructure (NI) and blue carbon storage (BC).

NOAA defines natural infrastructure as “healthy ecosystems including forests, wetlands, floodplains, dune systems and reefs which provide multiple benefits to communities including storm protection through wave attenuation or flood storage capacity and enhanced water services and security.” Coastal blue carbon storage refers to estuary systems such as salt marshes, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds that sequester vast amounts of greenhouse gas in their soils, in addition to serving as fish nursery habitat, migratory bird habitat, and supporting local economies in many ways.

We have gone beyond the conversation about “if” there is climate change to one about “when” and “how much.”

In his introduction to the report, Mr. Daniel Hayden, President and CEO of Restore America’s Estuaries, points out that 2020 set a new U.S. record, with $20 billion in costs associated with climate disasters. It was the sixth consecutive year in which ten or more $1 billion dollar disasters occurred (and the 10th year in a row with eight or more such events).

This report outlines in detail how much the U.S. has to lose if we do not protect and conserve our estuaries, but conversely how much we have to gain if we invest in natural infrastructure and blue carbon systems. Coastal wetlands, oyster reefs, sand dunes and sea grasses buffer storm surges, capture and filter flood water, all while providing habitat for wildlife and the natural beauty that is so vital for human well being and economic prosperity.

This study builds on the work completed in 2009, “The Economic and Market Value of Coasts and Estuaries: What’s At Stake?,” a report by NOAA in collaboration with Dr. Charles Colgan (Director of Research at the Center for the Blue Economy, a key author of both the 2009 and 2021 studies) and the Ocean Foundation, at the request of Restore America’s Estuaries. Like the 2009 study, the 2021 update uses the same data sources (Census, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bureau of Economic Analysis and NOAA), and looks in detail at the same five major sectors of the U.S. economy (fisheries, energy infrastructure, marine transportation, real estate, and recreation) from 2009-2018.

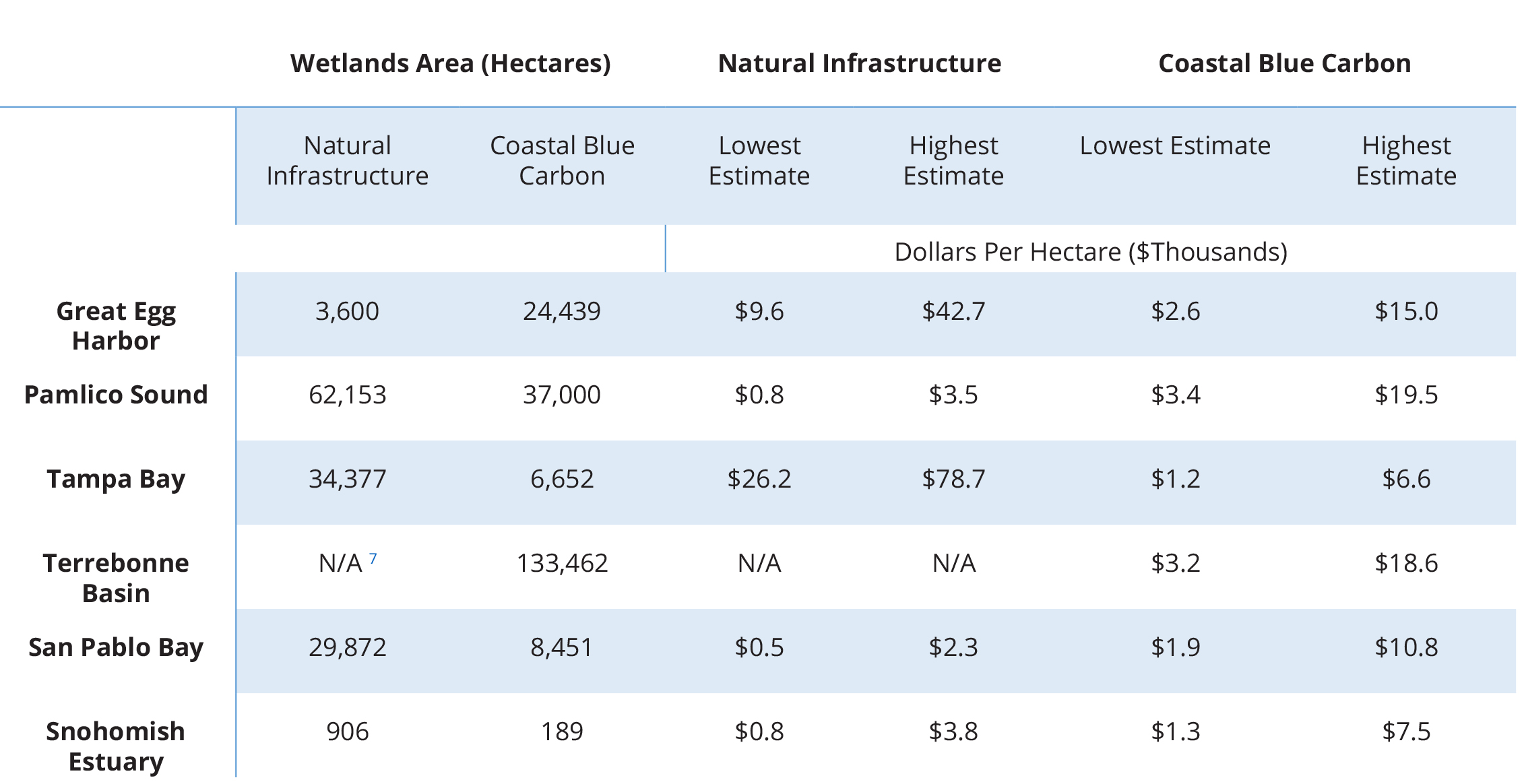

The 2021 update includes the economic value of natural coastal infrastructure and coastal blue carbon storage for six regions:

• Great Egg Harbor, New Jersey

• Palmico Sound and the Lower Neuse River, North Carolina

• Tampa Bay, Florida

• Terrebonne Basin, Louisiana

• San Pablo Bay, California

• Snohomish River Estuary, Washington

For the six areas above, a thirty-year data set,1970-2020, was included in addition to the key economic metrics, drawn from NOAA data and premised on two fundamental principles: First, that natural infrastructure and blue carbon value is derived from the ability of these systems to avoid future economic damages; Secondly, and most important, the actual value is dependent on keeping existing wetlands intact. The reduction or elimination of flood losses and the avoided release of carbon stores are what determine the economic value.

Regional Analysis Conclusions

Key findings from the Regional Analysis include:

- From 2009-2018, employment and GDP grew faster in estuary regions than in the U.S. as a whole.

- The pace and location of economic and demographic changes within estuary regions are important long-term drivers of natural resource change.

- A key component of the estuary regions’ economy are those sectors directly connected to the oceans and Great Lakes.

- The largest Ocean/Great Lakes economic activity as measured by employment in this report is tourism and recreation, which is a labor-intensive sector.

- Population and housing changes within the estuary regions were relatively small between 2009-2018, with the exception of Georgia and South Carolina.

From 2009-2018, employment and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew faster in estuary regions than in the U.S. as a whole, while population and housing rates grew at a similar pace, indicating that the primary driver of change was economic rather than demographic growth.

Case Study Conclusions

Estimates of the economic value of natural infrastructure and blue carbon sequestration in estuaries (as measured by the avoidance of future flooding and economic damages, and based on the assumption of keeping the wetlands intact) contain uncertainty, and are best expressed as lying with a range of plausible optimistic and pessimistic assumptions about the future impacts of climate change.

The six case studies included in the 2021 report add significantly to our understanding of the economic importance of estuaries, showing that the value of America’s estuaries is much larger than traditional economic measures reveal. The methodology used in the case studies reported the natural capital value of wetlands for flood resilience and carbon storage based on present values over 30 year periods (all those details are well documented in the report itself, linked below). Although more work is needed before any broad characterizations can be made—the sample size is just too small—this report does provide a basis to start thinking about what criteria in estuaries needs to be present to drive certain types of value, and why measuring and monitoring that value over time is important.

“The Economic Value of America’s Estuaries, 2021 Report,” has two main purposes: to update our understanding of the contributions of estuary regions to the economy of the U.S, and to expand our understanding of those values by examining the values provided by reduction in flood damages (natural infrastructure function) and the value provided by storing carbon dioxide (the blue carbon function).

This report provides decision makers a methodolgically sound baseline for both of those criteria, and it provides the basis for some good news: we can mitigate the most dire climate impacts by investing in and protecting America’s estuaries, deltas, bays, coastlines and Great Lakes.

We can all agree that the environment is important and needs to be preserved. However, we fall down when deciding what to do, how much to spend, and what it will take. It’s a question about how to best allocate limited and contested resources; time, capital, labor. We know how much these things cost. What we often lack is a way to value natural environment. This project fills that gap by explaining the services provided by estuarine wetlands and what they’re worth in the economy. We now know very clearly what’s at risk and this will guide policy action at all levels.

For More Information

Read the Full Study: The Economic Value of America’s Estuaries, 2021 Report