Professor Anne Campbell Helps Shape Future of U.S. International Educational Programs with New Resource

| by Jason Warburg

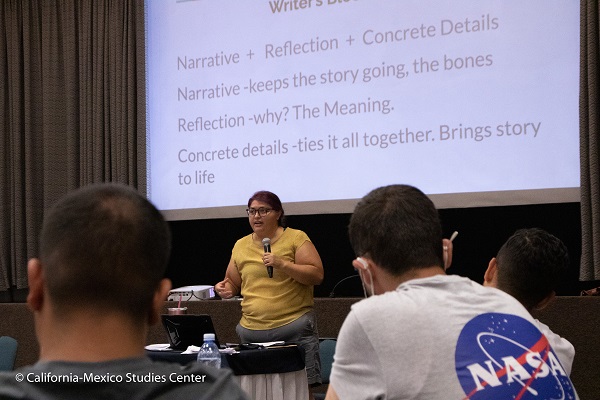

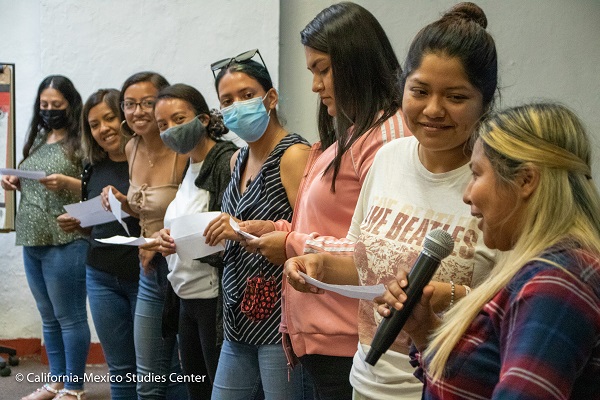

International Education Management professor Anne Campbell’s project for USAID to develop a toolkit for international scholarship programs also informed and enriched her classroom teaching at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies.