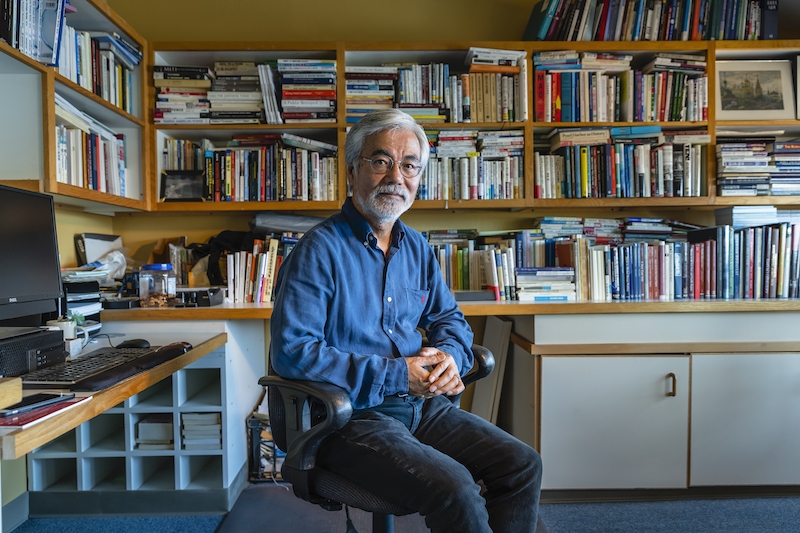

Life According to Langholz

| by Eva Gudbergsdottir

A fixture in the International Environmental Policy program, professor Jeff Langholz is nothing if not systematic in his approaches to life’s challenges. He generously shares his systems with students and colleagues, and is tireless in his efforts to inspire others.