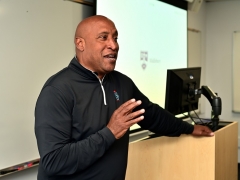

Why Our Leader-in-Residence Kicks Off His Communications Courses with Crisis

| by Mark Anderson

Vintage Foster, CEO of AMF Media Group, draws on his experience counseling companies and organizations on delicate and high-stakes situations for the class he’s been teaching at the Institute in strategic communications.